"The difficulty lies, not in the new ideas, but in escaping the old ones.” John Maynard Keynes

“If you don’t keep learning, other people will pass you by. Temperament alone won’t do it – you need a lot of curiosity for a long, long time.” Charlie Munger

"Read as many investment books as you can get your hands on. I've been able to learn something from almost every book I have read." Lee Ainslie

While many analysts dedicate their efforts to constructing spreadsheet models, the world's most successful investors prioritize reading and deep contemplation. The tutorials within the Investment Masters Class aim to uncover the underlying principles guiding their decision-making processes. Although each Investment Master possesses unique qualities, there are often shared insights and perspectives to be gleaned, enriching our understanding of investing. Delving into investor letters, interviews, and books can offer fresh perspectives on company analysis, uncover new investment opportunities, and foster insights previously overlooked. It's the cumulative acquisition of knowledge across various domains that cultivates wisdom in the realm of investment.

Over the years, I’ve learnt something from almost every book I've read (my favourites are here). Each book typically contains at least one or two ‘Investing Nuggets’ worth extracting. These nuggets can serve to reinforce existing beliefs, challenge previously held convictions, or even introduce entirely novel perspectives.

I've included five 'Investing Nuggets' below ...

The Alchemy of Finance [George Soros] - "escalator up, elevator down"

Mr Soros effectively defined his own theory for markets noting ‘existing theories about the behaviour of stock prices are remarkably inadequate. They are of so little value to the practitioner that I am not even fully familiar with them. The fact I could get by without them speaks for itself.’

The Alchemy of Finance provides an alternative explanation for asset bubbles, offering an explanation as to why markets tend to drift higher, yet decline rapidly. A market euphemism that ‘Stocks take an escalator on the way up and an elevator on the way down’.

Why should that be so?

Soros noted that markets can become irrational when participants lose sight of the fundamentals, ‘those who are inclined to fight the trend are progressively eliminated and in the end only trend followers survive as active participants. As speculation gains in importance, other factors lose their influence. There is nothing to guide speculators but the market itself, and the market is dominated by trend followers."

As all trends eventually end, ‘when a long term trend loses it's momentum, short term volatility tends to rise. It is easy to see why that should be so: the trend-following crowd is disorientated.’

It is then that the market can decline precipitously, ‘when a change in trend is recognised, the volume of speculative transactions is likely to undergo a dramatic, not to say catastrophic, increase. While a trend persists, speculative flows are incremental; but a reversal involves not only the current flow but also the accumulated stock of speculative capital. The longer the trend has persisted, the larger the accumulation.’

Soros concludes, ‘speculation is progressively destabilising. The destabilizing effect arises not because the speculative capital flows must be eventually reversed but exactly because they need not be reversed until much later. If they had to be reversed in short order, capital transactions would provide a welcome cushion for making the adjustment process less painful. If they need not be reversed, the participants get to depend on them so that eventually when the turn comes the adjustment becomes that much more painful.’

Capital Returns [Marathon Asset Management] - ‘… here comes the supply!’

This recent book edited by Edward Chancellor contains a collection of investment letters from the UK's Marathon Asset Management. The Marathon Global Equity Fund has delivered 9.7% pa since inception in 1986, outperforming their benchmark by almost 5% per annum.

The book is chock full of investing wisdom. The key theme of the book is an industry's 'capital cycle' and how that cycle impacts investment returns.

The book contains Marathon’s prescient newsletters on global house prices, credit markets and the commodity super-cycle. Each event resulted in significant investment losses for those investors oblivious to the capital cycle. Other letters reflect on capital allocation, industry dynamics, company culture, corporate management, technological disruption and the associated themes of 'network effects' and 'winner takes all'.

So what is the capital cycle? Marathon explains, ‘The first notion is that high returns tend to attract capital, just as low returns repel it. The resulting ebb and flow of capital affects the competitive environment of industries in often predictable ways - what we like to call the capital cycle’.

‘The key to the 'capital cycle' approach is to understand how changes in the amount of capital employed within an industry are likely to impact upon future returns.’

Most investors spend 90% of their time focused on the demand side of the equation, an area inherently subject to large forecasting errors. In contrast, Marathon spend the majority of their time focused on supply, which is far less uncertain.

Focusing on the magnitude of capital entering or exiting an industry can provide an investment edge, aiding the discovery of potential investments and/or highlighting risk to an existing thesis.

Influence [Robert Cialdini] - ‘why can't we change our minds?'

Charlie Munger has credited Robert Cialdini's bestseller, 'Influence' with filling many of the gaps in his mental framework.

The book contains a fascinating short story of a cult of thirty members of otherwise ordinary people - housewives, college students, a high school boy, a publisher, a doctor, a hardware-store clerk - which had been infiltrated by two scientific researchers.

The leader of the cult informed her members that she had begun to receive messages from 'Guardians', spiritual beings located on other planets. These transmissions gained significance when they began to foretell of an impending disaster - a flood that would eventually engulf the world. Alarmed at first, further messages assured the members they would be saved; before the calamity, spacemen were to arrive on a specific date and carry off the members in flying saucers to a place of safety, presumably on another planet.

Two specific aspects of the member's behaviour was noted by the two scientific researchers. First, the level of commitment to the cult's belief system was very high. Evidence included the irrevocable steps many members had taken; quitting their jobs and giving away personal belonging ahead of the 'specific' date. Secondly, members did surprisingly little to spread the word and avoided publicity when an inquiring newspaper started investigations into the cult.

On the 'specific' date, at the specified time, unsurprisingly, no spaceship arrived. The group seemed near dissolution as cracks emerged in the believers confidence. But then, the researchers witnessed a pair of remarkable incidents. The cult leader told the members she had received an urgent message from the Guardians stating, ‘the little group had spread so much light that God had saved the world from destruction’. Having previously shunned publicity, the cult leader then at once called the newspaper, to spread urgent message. Other members followed suit placing calls to various media outlets.

Mr Cialdini noted the group members had gone too far, and given up too much for their efforts to see them destroyed. From a young women with a three-year old child:

"I have to believe the flood is coming on the twenty-first because I've spent all my money. I quit my job, I quit computer school .. I have to believe."

So massive was the commitment to the cult that no other truth was tolerable. Member's beliefs should have been destroyed when no saucer landed, no spacemen arrived and no flood had come. In fact, nothing prophesized happened.

The group had one way out. Members had to establish another type of proof for the validity of their beliefs: social proof. The leader still believing let other members believe.

This short story helps explain why analysts and investors so often remain non-fussed in light of obvious disconfirming news about an investment - they are too committed. The fact other investors and analysts are steadfast in their views reinforces the behaviour. Watching stocks fail to respond to what should be negative news maybe a case in point. Everyone is watching each other.

Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits [Phil Fisher] - ‘… small price really’

Phil Fisher's writings are recommended by many of the great investors, Buffett, Munger and Li Lu included.

In 'Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits', Phil Fisher's analysis of factors that can sustain high profit margins reminded me of Berkshire's AGM this year when Munger, reflecting on competitive structure, divulged his preference for Precision Castparts above the reinsurance business. Munger opined that Precision Castparts’ customers ‘would be totally crazy to hire some other supplier because Precision Castparts is so much more reliable and so much better.’

Mr Fisher touched on the characteristics which can sustain high profit margins; a company can create in its customers the habit of almost automatically specifying it's products for re-order in a way that makes it rather uneconomical for a competitor to displace them.

When a reputation for quality and reliability in a company’s product is acknowledged as very important for the proper conduct of a customers business, the company is in a powerful pricing position. It’s even better if it’s likely an inferior or malfunctioning product would cause serious problems [think Aircraft parts!]. When there are no competitors serving more than a minor segment of the market the dominant company is nearly synonymous with the source of supply. Finally, the cost of the product should only be quite a small part of the customer's total cost of operations such that moderate price reductions yield only very small savings for the purchaser relative to the risk of taking a chance on an unknown supplier.

Mr Fisher went even further to note that even this was not enough to sustain an above-average profit margin year after year. The product needs to be sold to many small customers rather than a few large ones. The customers must be sufficiently specialized in their nature that it would be unlikely for a potential competitor to feel they could be reached through advertising media such as magazines or television. The company can be then displaced only by informed salesmen making individual calls. Yet the size of each customer's orders make such a selling effort totally uneconomical!

Such a company can, through marketing, maintain an above-average profit margin almost indefinitely unless a major shift in technology or a slippage in its own efficiency should displace it.

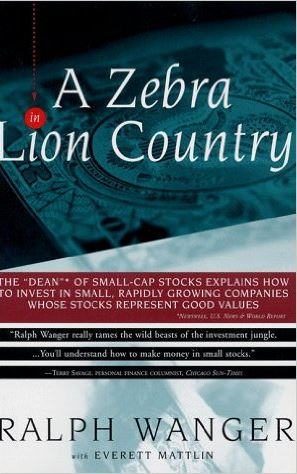

A Zebra in Lion Country [Ralph Wanger] - ‘who benefits from the technology?’

Ralph Wanger's 1996 book, 'A Zebra in Lion Country', contains a chapter titled ‘Downstream from Technology’, which discusses the opportunities and obstacle of new technology. In today’s era of disruption, it's worth thinking through the implications for investing.

Many of the Investment Masters are cautious in the technology sector due to short product cycles and the risk of technological obsolescence. As Mr Wanger notes, ‘New products are dangerous, especially in the computer field as technological breakthroughs bring price slashing every year.’

Mr Wanger continues, ‘What I have always looked for instead are the downstream users of new technologies. I’ve bought the stocks of companies that buy, use, and exploit the computers and electronics to reduce costs, revitalise their businesses, and add functionality to their products.’

‘Since the Industrial Revolution began, going downstream – investing in businesses that will benefit from new technology rather than investing in the technology companies themselves – has often proved the smarter strategy.’

‘Those who really made money out of the new technology (of steam locomotives) were not the transportation people but those who bought real estate in Chicago in the 1880’s and 1890’s.’

‘Recognizing a transforming technology and then investing downstream from it should be a key concept for any direct stock investor.’

‘With the internet small companies can now compete against giants.’

‘The armoured knights couldn’t beat armies of commoners with muskets, and the corporate nobility of today is similarly vulnerable to upstart companies with smart, energetic, and competitive management.’

The ability for companies to harness technology is not a new phenomena. Charlie Munger recognised the enormous value of technology that arrived with the invention of the VHS player.

‘Disney is an amazing example of autocatalysis .. They had all those movies in the can. They owned the copyright. And just as Coke could prosper when refrigeration came, when the video cassette was invented, Disney didn’t have to invent anything except take the thing out of the can and stick it on the cassette. And every parent and grandparent wanted his descendants to sit around and watch that stuff at home on video cassette. So Disney got this enormous tail wind from life. And it was billions of dollars worth of tail wind.’

More recently we've witnessed an exponential increase in digital disruption. The combination of Youtube, Facebook and Amazon webservers has allowed Dollar Shave Club to take on the once invincible Gillette. High speed internet has allowed Netflix to harness and monetise the world population causing havoc for free-to-air TV and cable operators and their finite markets. The internet and GPS has allowed Uber to disrupt the global taxi industry. Facebook and Google have disrupted the global advertising markets.

The future will bring increasing threats to old world industries who are not embracing technological change while providing the potential for significant investment opportunities. Maybe it’s time to look downstream.