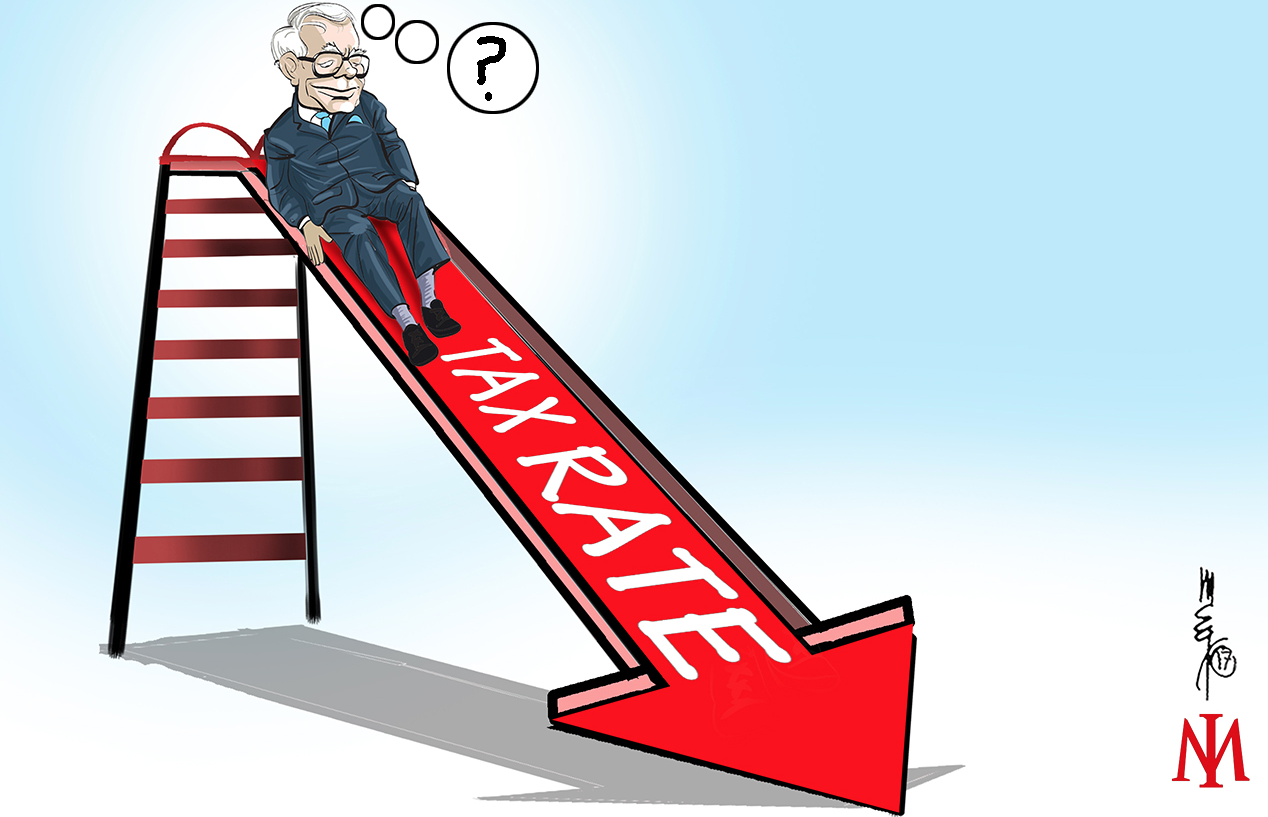

With the prospect of Corporate Tax cuts in the US post the election of Mr Trump it’s worth thinking about the implications for investments. Confronted with a change in the US corporate tax rate in the 1980's Buffett addressed the issue of winners and losers in his 1986 letter.

“The tax rate on corporate ordinary income is scheduled to decrease from 46% in 1986 to 34% in 1988. This change obviously affects us positively - and it also has a significant positive effect on two of our three major investees, Capital Cities/ABC and The Washington Post Company.”

I say this knowing that over the years there has been a lot of fuzzy and often partisan commentary about who really pays corporate taxes - businesses or their customers. The argument, of course, has usually turned around tax increases, not decreases. Those people resisting increases in corporate rates frequently argue that corporations in reality pay none of the taxes levied on them but, instead, act as a sort of economic pipeline, passing all taxes through to consumers. According to these advocates, any corporate-tax increase will

simply lead to higher prices that, for the corporation, offset the increase. Having taken this position, proponents of the "pipeline" theory must also conclude that a tax decrease for corporations will not help profits but will instead flow through, leading to correspondingly lower prices for consumers.

Conversely, others argue that corporations not only pay the taxes levied upon them, but absorb them also. Consumers, this school says, will be unaffected by changes in corporate rates.

What really happens? When the corporate rate is cut, do Berkshire, The Washington Post, Cap Cities, etc., themselves soak up the benefits, or do these companies pass the benefits along to their customers in the form of lower prices? This is an important question for investors and managers, as well as for policymakers.

Our conclusion is that in some cases the benefits of lower corporate taxes fall exclusively, or almost exclusively, upon the corporation and its shareholders, and that in other cases the benefits are entirely, or almost entirely, passed through to the customer. What determines the outcome is the strength of the corporation’s business franchise and whether the profitability of that franchise is regulated.

For example, when the franchise is strong and after-tax profits are regulated in a relatively precise manner, as is the case with electric utilities, changes in corporate tax rates are largely reflected in prices, not in profits. When taxes are cut, prices will usually be reduced in short order. When taxes are increased, prices will rise, though often not as promptly.

A similar result occurs in a second arena - in the price-competitive industry, whose companies typically operate with very weak business franchises. In such industries, the free market "regulates" after-tax profits in a delayed and irregular, but generally effective, manner. The marketplace, in effect, performs much the same function in dealing with the price-competitive industry as the Public Utilities Commission does in dealing with electric utilities. In these industries, therefore, tax changes eventually affect prices more than profits.

In the case of unregulated businesses blessed with strong franchises, however, it’s a different story: the corporation and its shareholders are then the major beneficiaries of tax cuts. These companies benefit from a tax cut muchas the electric company would if it lacked a regulator to force down prices.

Many of our businesses, both those we own in whole and in part, possess such franchises. Consequently, reductions in their taxes largely end up in our pockets rather than the pockets of our customers. While this may be impolitic to state, it is impossible to deny. If you are tempted to believe otherwise, think for a moment of the most able brain surgeon or lawyer in your area. Do you really expect the fees of this expert (the local "franchise-holder" in his

or her specialty) to be reduced now that the top personal tax rate is being cut from 50% to 28%?

Your joy at our conclusion that lower rates benefit a number of our operating businesses and investees should be severely tempered, however, by another of our convictions: scheduled 1988 tax rates, both individual and corporate, seem totally unrealistic to us. These rates will very likely bestow a fiscal problem on Washington that will prove incompatible with price stability. We believe, therefore, that ultimately - within, say, five years - either higher tax rates or higher inflation rates are almost certain to materialize. And it would not surprise us to see both."