“In 1850, a decade before the Civil War, the United States’ economy was small—it wasn’t much bigger than Italy’s. Forty years later, it was the largest economy in the world. What happened in-between was the railroads. They linked the east of the country to the west, and the interior to both. They gave access to the east’s industrial goods; they made possible economies of scale; they stimulated steel and manufacturing—and the economy was never the same.” W. Brian Arthur

Vanderbilt rode this wave like no other. He was rich. Filthy rich. At the peak of his wealth he owned the equivalent of one in every nine dollars in the United States. His heirs would build the largest mansions Americans had ever seen. Mansions that spanned New York’s city blocks and extravagant country estates like ‘Biltmore’, a gilded-age 250-room French Renaissance chateau that holds the title of America’s largest house to this very day.

Biltmore Estate, North Carolina

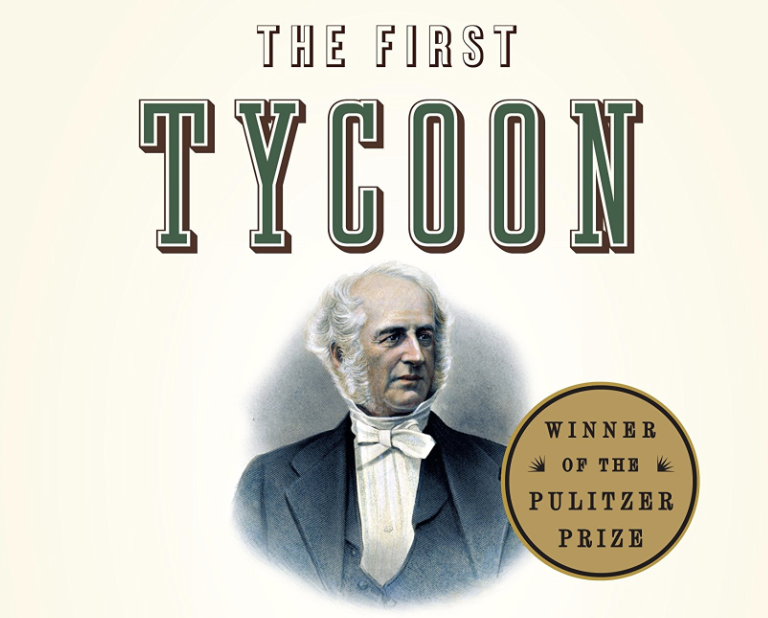

The ‘First Tycoon - The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt’ tells the fascinating story of Cornelius Vanderbilt, the business magnate who built an empire in shipping and then, at the ripe old age of seventy, in US railroads. Nicknamed ‘The Commodore’, Vanderbilt’s endeavours fighting brutal short-squeezes, double-crossing business partners, a race to provide passage across the Panama, personally saving the US stock market and the gifting of his largest ship to the Union Navy to fight the Civil War are relayed in vivid detail.

The book’s most useful learnings might relate to the insights into Vanderbilt’s business acumen. While they say history doesn’t repeat, it does rhyme, and despite two centuries passing since Vanderbilt first plied his trade ferrying cargo on New York’s harbour, the lessons in his business success remain as relevant today as they were then. I’ve included a collection of ‘Business Lessons’ extracted from this truly exceptional tome.

Grow the Market

Vanderbilt understood the benefits of increasing patronage by lowering prices; a strategy exploited in more recent times by SouthWest Airlines whose ex-CEO Herb Kelleher explains, ‘Charge low fares, get more people to fly, get them to fly more often, and you will produce the best return to shareholders.’

“Soon afterward he launched the Bellona on a new season of high-speed competition, powered by another cut in the fare to Philadelphia. The repeated price reductions were a stark departure from the past. They delivered a competitive advantage, of course, but also showed that Gibsons and Vanderbilt believed in a growing market – that more and more people wanted to travel between two cities, and would do so by steamboat if rates were cheap enough. This notion of an expanding economy was surprisingly new. The Livingstons’ North River Steam Boat Company had kept the same number of boats running to Albany at the same fare for years, and saw ridership steadily drop. They believed there was a natural number of passengers, and that competition was destructive, robbing them of their due.”

Increased Efficiency

“How do I make a profit? Vanderbilt would rhetorically ask in court in 1869. “I make it by a saving of the expenditures. If I cannot use the capital of that road for pretty nigh $2,000,000 per year better than anyone that has ever been in it, then I do not want to be in the road.” He would elaborate at length on his approach. “That has been my principle with steamships. I never had any advantage of anybody in running steamships; but if I could not run a steamship alongside another man and do it as well as he for twenty percent less than it cost him I would leave the ship.”

Lowest Costs

“Vanderbilt carried on the business war, the one he knew best. His and Mills’ ships continued to connect via Panama, rather than Mexico, but the Commodore’s prowess at cutting costs would allow him to slash fares until he had cut open the very arteries of the Accessory Transit Company.”

The Selfish Revolutionary

Fifth Avenue Mansion - Vanderbilt II

“For all his contradictions over the years, he remained the master competitor, the individual who did more to drive down costs and open new lines in steam navigatiuon than any other. More than that, he had helped shape America’s striving, productive society. Waging war with his business, he had wrought change at the point of the sword. He was the selfish revolutionary, the millionaire radical.”

Scale Advantages

“What he did not realise was that the world he had made himself – the world that gave rise to these individualistic, laissez-faire values – was beginning to disappear, thanks in part to his own success. He helped create enterprises on a scale never seen before in the United States. Small proprietors could not compete against him.”

Culture - Tone at the Top

“What Vanderbilt did was set general policies, as well as the overall tone of management. Any corporation has an internal culture shaped by the demands, directives, and expectations that rain down from above. The Commodore created an atmosphere of efficiency, frugality, and diligence, as well as swift retribution for dishonesty or sloth. Every employee knew he was watching.”

Customer Focus

“The testimony of Vanderbilt and his men produced ‘a decided change in public sentiment, which had previously run altogether in favour of the Central management,’ the Times reported. For one thing, Vanderbilt had a chance to present himself in his own terms. ‘I have always served the public to the best of my ability’, he remarked. ‘Why?, Because, like every other man, it is in my interest to do so, and to put them to as little inconvenience as possible.’”

Integrity, Shareholder Alignment

“His honesty attracted great admiration, for this was an era when even the best corporate officials routinely engaged in self-dealing, as they had since the first appearance of railroads in the 1830’s.”

“Thomas A. Scott, demanded kickbacks in the form of stock from outside contractors, such as sleeping-car and express companies. In the Central, Corning and other directors had ordered the company to purchase iron, goods, and services from their own firms. ‘The peculiarity of Mr. Vanderbilt’s railroad management,’ Putnam’s Monthly Magazine wrote, ‘is that instead of seeking to make money out of the road in contracts and side speculations, he invests largely in stock, and then endeavours to make the road pay the stockholders.’ The only compensation he accepted as president of his roads was in dividends on his own shares. ‘I manage it [a railroad corporation] just as I would manage my individual property. That is my notion, and the way I think a railroad ought to be managed,’ he told the assembly committee in February.”

Debt

“When I have some money I buy railroad stock or something else, but I don’t buy on credit. People who live too much on credit generally get brought up with a round turn in the long run. The Wall Street averages ruin many a man there, and is like faro.”

The Capital Cycle

“The Panic of 1873 started one of the longest depressions in American history - five straight months of economic contraction. In the next year, half of America’s iron mills would close; by 1876, more than half of the railroads would go bankrupt. Unemploynient, hunger, and homelessness blighted the nation. "In the winter of 1873-74, cities from Boston to Chicago witnessed massive demonstrations demanding that authorities ease the economic crisis," Eric Foner writes. The irony is that the fall was far more severe because of the rapid rise of the previous decade. The expanding, increasingly efficient railroad network had created a truly national market. The fates of farmers, workers, merchants, and industrialists across the landscape were tied together as never before. New York had cast its financial net across the country, which meant that credit flowed to remote regions far more easily than before but also that financial panics -affected the entire nation. As Vanderbilt pointed out, railroad overbuilding was an underlying economic problem, and it was exacerbated by Wall Street's craze for railway securities. When the bubble burst, the consequences were felt across the country with devastating suddenness and severity.”

New Business Enterprises, Lowered Prices, Dislocation

“And yet, even before the Commodore's death it was clear that the forces he had helped to put in motion were remaking the economic, political, social, and cultural landscape of the United States. There was the transparently obvious: the dramatically improved transportation facilities that allowed Americans to fill in the continent; the creation of enormous wealth in new business enterprises; and the railroads’ economic integration of the nation, bringing distant farms, ranches, mines, workshops, and factories into a single market, one that both lowered prices and dislocated older communities. (The new availability of western foodstuffs, for example uprooted New England farmers.) And there was the less obvious, such as the emergence of a new political matrix in which Americans struggled to balance the wealth, productivity, and mobility wrought by the railroads and other industries with their anxiety over the concentration of vast economic power in the hands of a few gigantic corporations. Though government regulation would emerge slowly and fitfully—fiercely opposed by many - it would take its place at the center of politics in the decades ahead.”

Engine of Social Revolution

“The importance of the railroad in the nineteenth century is a historical cliché; a cliché can be true, of course, but will have lost its force, its original meaning. Garrison's letter, on the other hand, speaks to the railroad's dramatic impact at the time of the Civil War. It was, one contemporary writer argued, "the most tremendous and far reaching engine of social revolution which has ever either blessed or cursed the earth." It magnified the steamboat’s impact, instilling a mobility in society that unraveled traditions, uprooted communities, and under-cut old elites. It integrated markets, creating a truly national economy.”

Evolve and Adapt

“The Commodore’s character played a role as well. Over the decades, his personality had evolved in parallel with his changing material interests. He had earned his reputation as a ferocious competitor in steamboats, a business notoriously prone to warfare, due to the low start-up costs and the inherent mobility of the physical capital - the steamers—which allowed a proprietor to fight on one route after another. It was also a time in his life when New York's merchant aristocrats derided him as a boorish outsider. After devoting himself to railroads, however, he had consistently pursued peace, seeking industry-wide agreements (though he remained ready to fight when attacked). The transformation reflected the nature of the railroad business, but it also suited his late-life status. The elite now thought of him as an "honorable & high toned" gentleman, precisely the sort of man who sought dignified arrangements, not economic bloodletting.”

Sacrifice Short Term Profits

“Time and again, Vanderbilt showed himself to be patient and diplomatic in dealings with Corning and Richmond, as he sacrificed short-term proficts for long-term stability.”

Decisive Strategic Advantages

“What did he see in it that no one else did? From the very beginning of Vanderbilt's career, he had focused on transportation routes that had decisive strategic advantages over competitors. The Stonington railroad for example, ran from a convenient port inside Point Judith over a direct line to Boston with easy grades that he made into the fastest and cheapest to operate at the time of his presidency. Likewise, the Nicaragua route to California had possessed a permanent superiority in coal consumption over Panama, thanks to shorter steamship voyages.”

Fixed Cost Leverage

“Vanderbilt sorely wanted the long-distance passengers and through freight that came from the West via the Central, no matter how little revenue he received. Unlike a steamboat and steamship line, a railroad suffered from high fixed costs. It was an immovable piece of infrastructure. Whether trains ran or not, the tracks, bridges, buildings, locomotives, and cars had to be maintained; conductors, engineers, firemen, and laborers had to be paid. At least two-thirds of a railroad's expenses remained constant no matter how much or how little traffic it carried. If the Commodore could get additional business, even at losing rates, it would improve the Harlem's outlook. To gain access to that rich flow of freight from the West, Vanderbilt decided to pursue diplomacy with the Central.”

Vanderbilt Residences - Fifth Avenue

Net Worth

“On the other hand, these figures do provide some context for the scale of Vanderbilt's fortune. If he had been able to liquidate his $1oo million estate to American purchasers at full market value (an impossible task, of course), he would have received about $1 out of every $9 in existence. If demand deposits at banks are included in the calculation, he still would have taken possession of $1 out of every $2o. By contrast, Forbes magazine calculated in September 2008 that William Henry Gates III—better known as Bill Gates—was the richest man in the world, with a net worth of $57 billion. If Gates had liquidated his entire estate (to American buyers) at full market value at that time, he would have taken $1 out of every $138 circulating in the American economy. Even this comparison under-states the disparity between the scale of Vanderbilt's wealth and that of any individual in the early twenty-first century, let alone his own time.”

Summary

Vanderbilt’s legacy provides timeless and universal lessons in business success. He thrived in an era of enormous technological change as railways revolutionised the American economy. Yet his approach to business is evident in many of the successful businesses we see today; tapping new markets through lower prices, respecting shareholders, sharing scale advantages and sacrificing short term profits for long term gains.

Vanderbilt was a legend. He held himself to a higher morale compass than his ruthless competitors. A lifetime spent in shipping proved no impediment to grasping the opportunity the nascent railway industry presented. Striving always for competitive advantages, Vanderbilt once again leveraged the benefits of scale to deliver his customers lower fares. For this he was amply rewarded. Incredibly so.

Reference:

‘The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt’ T.J Stiles, 2010.

Follow us on Twitter: @mastersinvest

TERMS OF USE: DISCLAIMER