Businesses Fade; its a fact. Market saturation, new competitors, management complacency and poor capital allocation all conspire against business growth. Today, corporate moats are being filled faster than ever as new technologies disrupt and challenge the prospects of what were once unassailable businesses. This process isn’t new. If you look back at the leading stocks of the S&P500 twenty years ago, few companies still hold those positions today. Given enough time, capitalism guarantees the demise of virtually all businesses.

Most analysts and investors understand this, correctly assuming a business’ growth will FADE.

“Investors tend not to believe in “longevity of compound.” Conventional thinking has it that good things do not last, and indeed, on average that’s right! Empirical Research Partners, an investment research boutique, discovered that the chance of a growth stock keeping its status as a growth stock for five years is one in five, and for ten years just one in ten. On average, companies fail.” Nick Sleep

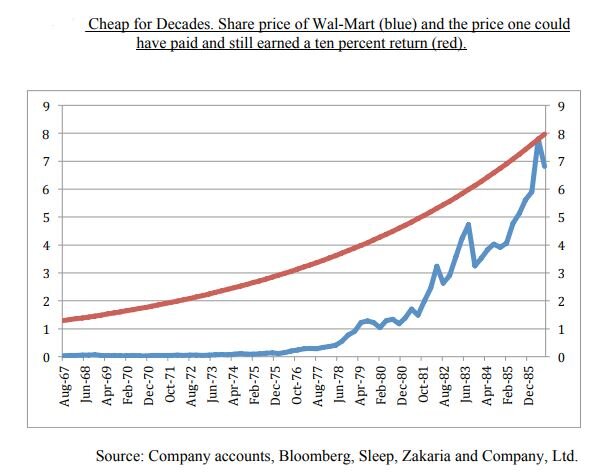

However, when the ‘mental model’ of mean reversion is applied to those rare FADE-defying companies, the estimate of value can not only be incorrect, but in the wrong ballpark. Both Nick Sleep and Terry Smith have drawn on examples to make this point. Nomad’s 2009 letter contained the following chart:

Sleep observed, “If, in 1972, upon reading that year’s twelve page annual report (!) an investor chose to make a purchase of shares, he could have paid over one hundred and fifty times the prevailing share price (a price to earnings ratio of over fifteen-hundred times, a ratio far in excess of what professional fund managers would consider prudent. They would be mistaken, as it turns out) and he would have still earned a ten percent return on his investment through to today. If, instead, the investor thought about it for a while and decided to purchase shares ten years later he could still have paid over two hundred times earnings for his shares (beware heuristics) and still earned ten percent on his investment. And ten years after that could also have paid a premium over the prevailing Wal-Mart share price and done well subsequently. The market struggled to appreciate the magnitude and longevity of the business’ success.”

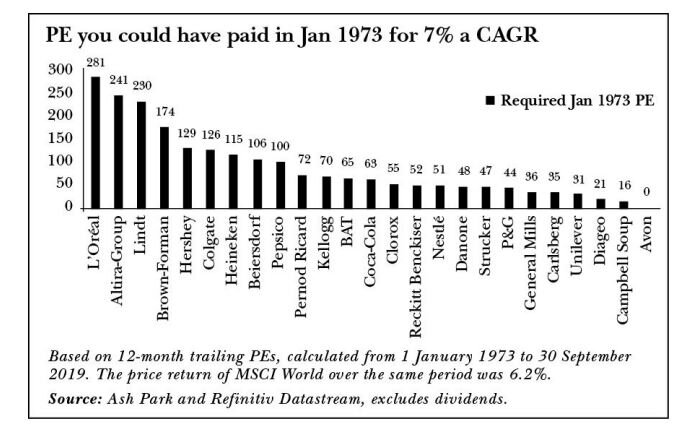

Terry Smith makes the following point in his new book, ‘Investing For Growth,’ “.. the level of valuation which may represent good value at which to buy shares in a high-quality company may surprise you. The following chart shows the “justified” PEs (price-to-earnings ratios) of a group of stocks of the sort we invest in. What does that mean? It looks at the period 1973 to 2019 when the MSCI World Index produced an annual return of 6.2% and works out what PE an investor could have paid at the outset for those stocks and still returned 7% p.a. over the period, so beating the index. You could have paid 281 times earnings for L’Oréal in 1973 and beaten the index return. Or a PE of 126 for Colgate. A PE of 63 for Coca-Cola. Clearly this approach would not fit the mutation of value investing in which the rating must simply be low. Yet it is hard to argue with the fact that these stocks would have been good value even on some eye-watering valuation metrics.”

While neither Smith nor Sleep advocate paying such extreme multiples for a business, their analysis highlights both the value that accrues to a business able to compound for extended periods of time and the disservice a simple price earnings multiple can afford great businesses.

Holding a variant perception on the sustainability of growth and resultant business worth can equip an investor with the fortitude to remain invested in these ‘compounding machines’. The unique characteristics misunderstood by the investing community often come in the form of business models, industry structures or the individual culture of the business. While by no means exhaustive, below we review four of these: ‘Scale Economics Shared’, ‘Increasing Returns’, ‘Market Dynamics’ and ‘Culture’.

Scale Economics Shared

‘Scale Economics Shared,’ a term coined by Nick Sleep, describes a business which shares the benefits of scale with it’s customers; ‘increased revenues begets scale savings begets lower costs begets lower prices begets increased revenues’.

These businesses optimise for longevity - not short term profitability. Persistent low prices attract customers, leading to increased turnover that drives scale benefits which are then returned to the customer in the form of even lower prices; a virtuous feedback loop. As the business grows, the moat gets wider.

“There are very few business models where growth begets growth. Scale economics turns size into an asset. Companies that follow this path are at a huge advantage.” Nick Sleep

It’s not new. Cornelius Vanderbilt, America’s first tycoon, built the greatest fortune America had ever seen employing this business model over two centuries ago. Buffett too, recognised this model decades ago. Berkshire’s 1993 letter touched on Nebraska Furniture Mart.

“They buy brilliantly, they operate at expense ratios competitors don’t even dream about, and they then pass on to their customers much of the savings. It’s the ideal business - one built upon exceptional value to the customer that in turn translates into exceptional economics for its owners."

Berkshire’s 1996 letter discussed Geico:

“There's nothing esoteric about GEICO's success: The company's competitive strength flows directly from its position as a low-cost operator. Low costs permit low prices, and low prices attract and retain good policyholders. The final segment of a virtuous circle is drawn when policyholders recommend us to their friends… the economies of scale we enjoy should allow us to maintain or even widen the protective moat surrounding our economic castle. We do best on costs in geographical areas in which we enjoy high market penetration. As our policy count grows, concurrently delivering gains in penetration, we expect to drive costs materially lower.”

Companies across diverse industries, Ford, Costco, Walmart, Southwest Airlines, Aldi, Amazon and Geico, have all delivered exponential wealth to their shareholders employing this business model.

“The business model that built the Ford empire a hundred years ago is the same that built Sam Walton’s (Wal-Mart) in the 1970’s, Herb Kelleher’s (Southwest Airlines) in the 1990’s or Jeff Bezos’s (Amazon.com) today. And it will build empires in the future, too.” Nick Sleep

Increasing Returns

Over the last decade, many tech giants have defied the fade. They’ve grown stronger and more profitable as they have evolved; first mover advantages have morphed into huge network effects. The Santa Fe Institute’s theoretical economist, W. Brian Arthur, recognised this potential in a groundbreaking paper published almost 25 years ago. ‘Increasing Returns and the New World of Business,’ presented a roadmap for what would become today’s tech titans.

“Increasing returns are the tendency for that which is ahead to get further ahead, for that which loses advantage to lose further advantage. They are mechanisms of positive feedback that operate—within markets, businesses, and industries—to reinforce that which gains success or aggravate that which suffers loss. Increasing returns generate not equilibrium but instability: If a product or a company or a technology—one of many competing in a market—gets ahead by chance or clever strategy, increasing returns can magnify this advantage, and the product or company or technology can go on to lock in the market.” W. Brian Arthur

Arthur recognised the capital-light nature of technology businesses meant they could become entrenched in a winner-take-most scenario. High upfront costs (‘The first disk of Windows to go out the door cost Microsoft $50 million; the second and subsequent disks cost $3. Unit costs fall as sales increase’), network effects and customer lock-in all serve to increase business sustainability over time.

“Western economies have undergone a transformation from bulk-material manufacturing to design and use of technology—from processing of resources to processing of information, from application of raw energy to application of ideas. As this shift has occurred, the underlying mechanisms that determine economic behaviour have shifted from ones of diminishing to ones of increasing returns.” W. Brian Arthur

Charlie Songhurst, a Microsoft alumni and prolific investor, recognised the limitation of applying typical fade metrics to ‘increasing returns’-type businesses.

“I think one thing that's very interesting is the way you model companies in Excel with a DCF, there's this sort of set of cultural norms, like trending down the growth rate to a terminal value over time that obviously we collect for industrial era companies. It's obviously the right concept [for industrial era companies]. Maybe that's just not right for network effects businesses because instead, literally, how do you model in Excel the concept of in year six, something becomes a standard and therefore gets sustained to accelerating growth? There was some sort of joke in the eighties that you'd never get fired for buying IBM. Well maybe in 2006, it suddenly became you never got fired for buying salesforce.com. How do you model in that as a concept? Suddenly kicking into revenue growth, maybe what you should actually be doing is writing a 3,000 word essay on revenue growth drivers, as opposed to sort of trending down over time as an automatic default.” Charlie Songhurst

Addressable Market / Market Opportunity

It’s obvious that a business starting from a smaller base has a much bigger runway for growth; the law of large numbers makes it hard for businesses to grow at high rates for long periods. Even with this understanding, investors and analysts often misjudge a potential market opportunity. When Southwest Airlines enters a new market they liberate a new class of customers by dramatically cutting fares and increasing frequency; market size can rise by a factor of eight.

“When evaluating market size, it’s also critical to try to account for how lower costs and product improvements can expand markets by appealing to new customers, in addition to seizing market share from existing players.” Reid Hoffman

“When you materially improve an offering, and create new features, functions, experiences, price points, and even enable new use cases, you can materially expand the market in the process. The past can be a poor guide for the future if the future offering is materially different than the past.” Bill Gurley

Often an adjacent market can be tapped by an enterprising business. The obvious example is Amazon’s move beyond books. Uber and food delivery, Airbnb and hotels, Nike and casual wear are further examples.

“When Amazon listed at the height of the dot.com boom in the late 1990’s, even the most bullish analysts thought that the total addressable market for Amazon was $26 billion, which equated to the total size of the book market in the US.” Helen Xiong

“We didn't really foresee back 20 years ago that the sport shoe business could get so big.” Phil Knight

“We should ban all talk of TAMs – the total addressable market – these are spot numbers in any other guise and useless in my view. Ten years ago, did anyone imagine the success of Amazon Web Services or YouTube? The supposed experts had no conception of how large cloud computing might become or how many smartphones would be sold. Tesla’s potential in the mass market today looks rather different than when the company produced the first Roadsters, etc. The point here is not to constrain ourselves to a point in time – great companies innovate to create new areas of opportunity and by doing so help to prolong their corporate life.” Mark Urquhart

Reflecting on Sequoia’s investment in Cisco, Michael Moritz noted that the relentless decline in computing costs kept expanding the size of markets Sequoia-backed companies could pursue — a reminder that future returns should always eclipse the past as technology drives new demand.

“Our distribution of Cisco taught me two lessons. The first was that the decline in computing cost would continue to expand the size of markets that Sequoia-backed companies can pursue, thus making it possible for several more generations to always top the returns of their predecessors. That remains true today — our future returns should always eclipse our past returns. The second lesson was that the leading company in a rapidly growing market can flourish for years if not decades. As Cisco’s revenues and profits continued to grow, the value of the company followed suit. By 1993 Cisco’s market cap reached $7 billion and by 1994 (the year in which Cisco first appeared on the Fortune 500) it exceeded $10 billion. At the end of 1998, before the world was completely swept up in the dotcom hurricane, Cisco had a market value of $176 billion. Eventually, I learned another lesson, ‘Anything is Possible.’” Michael Moritz

“In the tech space, investors repeatedly made the mistake of assuming that the size of the market opportunity for growing companies was capped by the size of the market they were disrupting. Many examples spring to mind where this was the case. For example, Google’s and Facebook’s market opportunity was thought to be capped by the size of the advertising market (the largest part of which historically was TV advertising in which only the largest 100 or so companies in any country could participate). Facebook today has over ten million advertisers.” Robert Vinall

“Newer companies are opening up new markets and it’s easy to undersize the TAM. Is Uber or Lyft replacing taxis or reinventing car ownership?” Philippe Laffont

Deriving the scope for a market from an incumbent can seriously under-estimate the addressable market. I recall when realtor ads first moved on-line, analysts dampened their growth expectations for a listed company which achieved winner-take-all status. The analysts failed to appreciate the opportunity to take a greater share of the customer’s wallet by monetising on-line video tours, which weren’t possible with newsprint.

“Sizing the market for a disruptor based on an incumbent’s market size is like sizing a car industry off how many horses there were in 1910.” Aaron Levie

Management & Culture

Everyday businesses face competitive challenges, threats and opportunities; capitalism is a brutal force and change is constant. If a business is to survive and prosper it must adapt and evolve. It’s the company’s management and people that ultimately determine the long term success of a business.

Businesses sustainability is enhanced in the presence of a culture of continuous learning, trial and error, accepting of mistakes, innovation, quality and customer focus. Respect and care for a business’ ecosystem - employees, customers, shareholders, suppliers, the community and environment - is critical to long term success. The management team must set the right example, be aligned with shareholders and focus on the long term.

“A business’s product differentiation is not an enduring moat. If the differentiation has any merit, it will eventually be copied and advantages will soon be frittered away. Xerox, Kodak, BlackBerry and countless other businesses once held product dominance and fell to this fate. The only moat that is not fleeting, and conversely the only moat that is truly enduring, is culture.” Christopher Begg

“Culture trumps everything else in the long term. What do I mean by culture? Simplistically, it’s where companies are genuinely run for the long term.” Helen Xiong

Summary

When it come’s to long term business success, sharing scale benefits with the customer, grasping increased returns, optimising your market and ensuring an enduring culture can go a long way to fight the FADE that inflicts typical businesses. The companies that benefit from a few of these are likely to be long-term success stories. Those that utilise all may become tomorrow’s titans. Amazon is a case in point.

And for those investors who recognise and incorporate these characteristics in their investment process, the rewards can be lucrative. It’s time to search out those businesses where the ‘mental model’ of mean reversion is unbefitting - then all you have to do is simply sit on your ass.

“It’s a simple statement of fact that there have been great growth companies that have defied the skepticism of Graham and the mantra of mean reversion. They have endured for decades even at massive scale. I don’t see this as a contention but as an observation. Ironically they’ve altered the patterns of stock market return sufficiently that the very utility of the ‘mean’ has been undermined. The mean is now so far above the median stock that our entire notion of the distribution of returns has to be reviewed. The first chance to reassess came with Microsoft over 30 years ago. The investment community has been slow indeed. We can react to economic data or quarterly earnings in seconds but adjusting our world view has proven far harder.” James Anderson

Further Suggested Reading:

“What Goes Up Must Come Down: Must It Not?” - Nick Train, Lindsell Train 2012

“Graham or Growth - Concluding Thoughts.” - James Anderson, Baillie Gifford, 2020

“Increasing Returns and the New World of Business.” - Brian Arthur, HBR, 1996.

“How to Miss By a Mile: An Alternative Look at Uber’s Potential Market Size.” - Bill Gurley, Above the Crowd. 2014.

Follow us on Twitter : @mastersinvest

TERMS OF USE: DISCLAIMER