Outperforming the market is hard. Over the last five years, it was easy. Easy if you owned just one stock. The world’s largest. You just had to buy Apple. And NOT sell it.

John Huber of Saber Capital touched on this in his annual letter:

“Over the past 5 years, with exceptions that you could probably count on two hands, Apple has outperformed the entire hedge fund industry, every one of the 10,000+ mutual funds, the passive funds at Vanguard and Blackrock, the most prestigious private equity funds, and the vast majority of venture capital funds in Silicon Valley. We’re talking about many trillions of dollars in all kinds of investment vehicles with all kinds of fees, managed by extremely smart people with unlimited research budgets and super smart employees, who all work extremely hard, and are all highly incentivized to produce great results. And Apple beat nearly every last one of them.”

When it comes to investing mistakes, most people think in terms of what’s been bought, not sold. Yet, selling a stock can be the biggest mistake there is.

“Of our most costly mistakes over the years, almost all have been sell decisions.” Chris Cerrone

“By far, the biggest mistakes I’ve made is selling stock early. As an example, we made a big investment in Tencent in 2003 and having sold that position early cost the fund twenty billion dollars.” Philippe Laffont

"The biggest mistake an investor can make is to sell a stock that goes on to rise ten-fold. It's not from owning something into bankruptcy. But that's what everyone thinks, at least judging by the questions we get from clients." Nick Sleep

"Over time, any honest investor and especially any honest value investor will tell you that their biggest mistakes were what they sold, not what they bought." Chris Davis

"The biggest mistake you can make is not failing to sell something you should have sold, it's selling something that you should have held on to.” Tom Slater

“If I’ve made one mistake in the course of managing investments it was selling really good companies too soon. Because generally, if you’ve made good investments, they will last for a long time.” Lou Simpson

“As the old saying goes: ‘it’s never wrong to take a profit’. But it is often not just wrong but the worst mistake that can be made.” James Anderson

“Selling early is the high blood pressure of the investment business. It’s a silent killer. And you know, people will always talk about the business they bought that went to zero, or the one that went down 50% or 75%. Yes, that’s bad. You want to avoid that but the business that you sold too early, that went on the compound tenfold, or 20-fold after that in my career, has been a real killer.” Peter Keefe

“Investor should be especially careful with their winners – selling too early is the most overlooked detractor from long-term outperformance.” Shad Rowe

Some of the best track records in investing have come from those investors who’ve identified great companies and ridden them. Whether it’s Li Lu, Terry Smith, Nick Train, Nick Sleep, Chuck Akre, Francois Rochon, Shad Rowe, Dan Davidowitz, Ted Weschler or Warren Buffett, they’ve chosen a different path to most investors. They view companies through a different lens and have delivered market crushing returns as a result.

Charlie Munger dubbed this approach, ‘Sit On Your Ass’ investing.

A few years ago I penned a piece titled, ‘When to Sell a Great Company?’ The conclusion was, almost never. I enjoyed a recent post by Chris Cerrone of Akre Capital titled ‘The Art of [Not] Selling’, aka ‘Sit on Your Ass’ investing. The article inspired me to finish a post which had been sitting dormant in my ‘drafts’ for the last year. I’ve woven elements of Chris’ article with investing insights from some of the eminent investors mentioned above.

While ‘Sitting On Your Ass’ sounds simple. In practice, it’s not. Ahead are some tips to help you remain seated when everyone else has decided to get out.

Let’s start with some of the attractions of ‘Sit on Your Ass’ Investing:

Availability

As much as I enjoy reading about Jim Simons, Ray Dalio, George Soros, Paul Singer, Stanley Druckenmiller and Howard Marks, their investment style is near impossible for Joe Average to replicate. That’s unless you’ve got a team of code cracking PhD’s, employ a hundred uncorrelated multi-asset strategies, have an intuitive leveraged global macro trading capability, a structurally hedged activist style or deep expertise in distressed assets.

The beauty of ‘Sit on Your Ass’ investing is that it’s available to everyone.

Lower Transaction Costs / Taxes

A benefit of not trading is avoiding short term capital gains tax, meaning less dollar leakage and a larger asset base to compound. Lower turnover also means less frictional costs like commissions and market impact.

“Sit on your ass investing. You’re paying less to brokers, you’re listening to less nonsense, and if it works, the tax system gives you an extra one, two, or three percentage points per annum.” Charlie Munger

“One of the key roles I’ve played at Peninsula on your behalf over the past 12 years is resisting the temptation to sell - doing nothing can run counter to a serious work ethic, but in the world of investing it can be a very effective strategy in that it: i) minimises transaction costs, ii) minimises taxes, and iii) respects the fact that as a practical manner, market timing is a fool’s errand.” Ted Weschler

“When you sell a stock you’ve got to be right twice. You gotta pay taxes and replace the investment. On a growth stock you just have to right once.” Shad Rowe

“Strong companies also offer us the chance at long-term compound growth in capital appreciation without incurring taxes, which essentially serves as an interest-free and recourse-free leverage from government taxing authorities.” Li Lu

Fewer Decisions / Less Re-Investment Risk

A strategy of buying stocks cheaply to sell higher requires a constant supply of new ideas. Not only do you have to get the buy decisions right, but the sells too, and in perpetuity. ‘Sitting on Your Ass’ requires fewer decisions and allows more time to get acquainted with the companies you own.

“What we really like is buying good-sized to very large first-class businesses with first-class management and just sitting there. You don’t have go from flower to flower. You can just sit there and watch them produce more and more every year.” Charlie Munger

“If our firms can successfully grow, and we can resist the temptation to fiddle, then we can meaningfully reduce the reinvestment risk embedded in lots of share buying and selling.” Nick Sleep

Harness Compounding

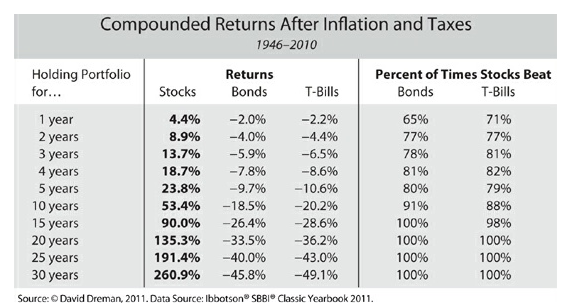

The human brain is wired to think linearly not exponentially. Chris Cerrone reminds us that a penny doubled everyday for a month turns into $10,737,418.24! Of course, there’s no better investor to demonstrate the extraordinary power of compounding than Warren Buffett, who’s life has been the ‘product of compound interest’. The following table pretty much says it all.

The Power of Compounding - Warren Buffett vs The Market [Source: Visual Capitalist]

“A great company keeps working when you’re not. A great company will eventually earn more and more and more while you’re just sitting and doing nothing. And a mediocre company won’t do that. So you’re harnessing a long range force that will help you. It’s very important.” Charlie Munger

‘Sit on Your Ass’ investing leverages the growth in a business’ intrinsic value. Terry Smith, a dyed-in-the-wool ‘Sit on Your Ass’ investor, touched on this in his recent letter.

“Equities are the only asset in which a portion of your return is automatically reinvested for you. This retention of earnings which are reinvested in the business can be a powerful mechanism for compounding gains.”

Rare Quality Businesses

A multitude of factors impact stock prices in the short term; quarterly earnings, investor sentiment, macro developments, valuation re-ratings, analyst recommendations, etc. As the holding period lengthens, business performance exerts a greater influence on stock prices.

The best businesses for long term investment therefore are those with both ‘enduring’ high returns on capital and attractive reinvestment opportunities.

‘Enduring’ high returns require sustainable competitive advantages to protect the business from the vagaries of capitalism. These businesses are often referred to as ‘Compounding Machines’.

“We endeavour to look past the non-essential details. We want to identify the essence of each business’s competitive advantage.” Chris Cerrone

These businesses are few and far between. As such, businesses worthy of ‘Sit on Your Ass’ investors tend to represent sizable positions in their portfolios.

“Companies with truly unusual prospects for appreciation are quite hard to find for there are not too many of them.” Phil Fisher

“There's only a tiny number of exceptional companies.” Reece Duca

“Truly strong companies with sustainable competitive moats are rare.” Li Lu

“Good investment ideas, that is, companies that meet our criteria, are difficult to find. When we think we have found one, we make a large commitment.” Lou Simpson

“Exceptional companies with durable competitive advantages are rare.” Nick Train

“Good ideas are too scarce to be parsimonious with once you find them.” Warren Buffett

Long Runway

Growth is an essential element. Businesses that don’t grow are unlikely to be profitable long term investments.

“The real money is going to be made by being in growing businesses, and that’s where the focus should be.” Warren Buffett

“The runway ahead for our businesses may be very long indeed.” Nick Sleep

"In our office we often say, ‘How wide and how long is the runway’?" Chuck Akre

Macro Concerns

Macro issues often spook investors out of positions; trade wars, Fed policy, GDP growth, politics and geopolitical tensions are but a few. These short-lived facts and data points rarely have a bearing on a business’ long term value.

Businesses stress tested by previous economic cycles, with solid balance sheets, good management and sustainable competitive advantages survive.

“We try hard to tune out concerns about politics and the economy. We read the newspapers, and we work just down the road from Washington D.C. However, it has been our experience that we are at our worst as investors when we allow concerns about these issues, including elections, trade wars, and Fed policy, to influence our investment decisions.” Chris Cerrone

“Charlie and I spend essentially no time really thinking about macro factors.” Warren Buffett

Adopting the mindset of a business owner as opposed to a stock trader can help. Would a business owner sell their private company based on a tweet by Trump, a lower GDP print or a strategist forecast?

“Our business owner mentality.. allows us to virtually ignore the constant babble of short term macro noise." Allan Mecham

Destination Analysis

The myopic market focus on the short term provides opportunity for mis-priced opportunities in the long term. Wall Street analysts publish valuations and price targets with scant regard to where a business might be in five or ten years. Armed with a deep understanding of a business’ DNA, an investor can overlook short term operating results and reflect on how a business might be positioned five or ten years hence.

“We always focus on what the business will look like in the very long term.” Zhang Lei

“We patiently build up core expertise that allows us to evaluate the long term prospect of the businesses we are interested in.” Li Lu

“We’re trying to figure out what this businesses is going to look like five years from now and ten years from now, not what’s going to happen in the next quarter or the next year.” Dan Davidowitz

Focusing on the destination can also help an investor stick with a position, even after periods of significant outperformance. Nick Sleep articulated this point with regard to Amazon in his 2007 letter:

‘To those who argue Amazon is large already we ask two questions: What do you think e-commerce will be as a proportion of US retailing in ten years, and what do you think it was last year?

After doubling in the share price and the weighty resultant position in the Partnership it would be easy to claim victory, high five, and sell our shares in Amazon. However, the high weighting makes sense given our understanding of the destination of the business and the probability of reaching that destination. We have argued that the biggest error an investor can make is the sale of a Wal-Mart or a Microsoft in the early stages of a company’s growth. Mathematically this error is far greater than the equivalent sum invested in a firm that goes bankrupt. The industry tends to gloss over this fact, perhaps because opportunity costs go unrecorded in performance records. We wonder, would selling Amazon today be the equivalent mistake of selling Wal-Mart in 1980?”

Valuation

“To the surprise of many, neither valuation nor price targets play a role in our sell decisions.” Chris Cerrone

“Another question we often get from investors concerning valuation: Do you assign price targets for your companies? The answer is no. Price targets strike us as too precise and, as importantly, potentially limiting to total return if one feels compelled to sell once the stock reaches the price target.” Dan Davidowitz

“The opportunity to buy the shares of a great company at a fair price is rare. So, selling a great company because it surpasses an arbitrary price target after six, 12, or 18 months seems on its face to be counterproductive and tax-inefficient.” Shad Rowe

A high multiple doesn’t imply a stock is a poor investment. The power of compounding can render an ‘optically expensive stock’ cheap very quickly.

Valuations are inherently imprecise. Most analysts’ DCF models assume a company’s growth and returns mean revert in time. Businesses with enduring competitive advantages that can resist this reversion are likely to be worth significantly more than typical finance models suggest.

In addition, great management teams have a tendency to enhance value through time.

“The very best businesses tend to exceed expectations. What may seem like a high price today may be proven to be perfectly reasonable in hindsight.” Chris Cerrone

“I have noticed that the truly great companies and great managers generally get better over time.” Shad Rowe

This suggests valuation should carry less weight in the investment decision.

“We really have a great reluctance to sell businesses where we like both the business and the people. So I don’t think I’d count on seeing many sales. But if you ever attend a meeting here, and there are 60 or 70 times earnings, keep an eye on me.” Warren Buffett, 1996

“Selling great companies with large growth potential, even at seemingly rich valuations, is usually a mistake.” Allan Mecham

Position Sizes / Volatility

Not selling a stock that delivers exceptional returns can result in a quality problem; the stock becomes a large part of the portfolio. Ted Weschler’s position in W.R Grace & Co. was almost 50% of his fund before he closed Peninsular to join Berkshire Hathaway in 2011. When Nick Sleep closed Nomad Partners in 2014, Amazon had grown to represent more than thirty percent of assets. Chuck Akre’s position in Speedway had grown to c50% of his portfolio in 1993 despite trimming a third of the position over the previous two years. And when Li Lu delivered a 200%+ fund return in 2009 as BYD skyrocketed 400%, BYD constituted over 50% of his partnership.

When positions get large, future fund returns become increasingly influenced by such positions. Li Lu’s 2009 annual letter noted, “the extreme appreciation [of BYD] has made the stock constitute a very large portion of our portfolio. This will lead to more volatility going forward.”

A large position can also constrain decision making if it leads to commitment bias. Li Lu’s fund struggled in 2010 and 2011 as the BYD share price declined nearly 80% from its 2009 high. By the end of 2012, the position size still represented one third of the fund. By 2014, the position size had been substantially reduced [to c10%] as a result of new investments by limited partners and other portfolio gains. With the benefit of hindsight, Mr Lu questioned his decision regarding the proper sizing of BYD after the market gains became so large. In the end he felt commitment bias [via a prominent association with the company and loyalty to its top leadership] had constrained his decision making.

Aligned Investors

Investor alignment is paramount in light of the potential for outsized positions and volatile returns.

Educating investors and preparing them for an absence of portfolio activity is a sensible strategy.

“One common psychological trap that agents may fall into is that clients expect action, or to be more accurate, fund managers expect their clients to expect action! The investor Seth Klarman was once challenged on whether Buffett’s track record was statistically significant as he traded so little? To which Klarman answered that each day Buffett chose not to do anything was a decision too.” Nick Sleep

"If we were private business owners/investors, long spans of inactivity would raise no eyebrows. No reasonable person would expect a farmer to sell his farm in order to buy a different farm every decade, let alone every year or several times a year. As public -market investors, however, this ‘sitting on our hands’ behaviour is unusual." Clifford Sosin

“‘He really doesn’t Do anything. All he does is buy and hold. What I need are people who make money’ is a comment I occasionally hear from arithmetically challenged investors. I plead guilty. What we attempt to do is simple – identify great companies that fit within compelling long-term themes . . . companies that do something better, faster and cheaper FOR instead of TO their customers, with balance sheets big enough to go after huge opportunities. We attempt to buy shares at reasonable prices, and then hold on (hopefully forever).” Shad Rowe

Patience

Pascal observed, 'The hardest thing for a man to do is sit quietly in a room'. Charlie Munger and Warren Buffett have insurance and operating businesses to occupy them. Over the years I’ve noticed some investors, Warren Buffett included, have played around the edges in different investments while leaving their ‘quality’ companies well alone - a strategy worthy of consideration should it override a temptation to sell.

“It’s waiting that helps you as an investor, and a lot of people just can’t stand to wait.” Charlie Munger

“Investing is a mind game. If you are in a rut as a concentrated investor, increase your chances of winning and add a couple positions. It also lets you breathe and your positions breathe a bit.” Ian Cassell

Pot Holes

Expect pot holes. Business performance, like stock returns, aren’t linear. Businesses have hiccups. Ensure they are temporary not structural.

“I don’t expect the best companies to show their excellence every quarter.” Li Lu

"Businesses do not meet expectations quarter after quarter and year after year. It just isn’t in the nature of running businesses." Warren Buffett

“It’s in the nature of things that the market is not going to do exactly what you want, when you want it.” Charlie Munger

Many of the great ‘Sit on Your Ass’ investors, Terry Smith, Li Lu, Warren Buffett, Francois Rochon, and Nick Sleep included, look to their companies operating results to judge progress, not stock prices.

“I introduced the concept of viewing our entire portfolio as a single ‘HCI Holding Company” based on the weighted average of our shares in each individual portfolio company. This is a very useful way to understand our activities since we view ourselves primarily as owners of businesses and hold our positions for a very long time with very low turnover.” Li Lu

When To Sell

Mr Cerrone sets out three criteria where Akre Capital may sell a stock; slowing growth, loss of competitive advantage or adverse new management. You’ll note they are all related to the operating characteristics of the business, not the soap opera of the market place or macro considerations.

“We sell really when we think we're re-evaluating the economic characteristics of the business. We probably had one view of the long-term competitive advantage of the company at the time we've bought it, and we may have modified that.” Warren Buffett

“When we become concerned about the strength of a company’s franchise, its competitive advantage, or its balance sheet we will sell immediately.” Dan Davidowitz

The major risk when adopting a ‘Sit on Your Ass’ investment approach is mis-analysis of the business. It’s all about the business and its future.

“What costs us money is when we mis-assess the fundamental economic characteristics of the business.” Warren Buffett

“In our opinion, the biggest risk in investing is the risk of mis-analysis.” Nick Train

Summary

If you’ve been a reader of my posts over the last few years, you will have no doubt noticed the commonality of the world’s best investors and their collective thinking regarding what constitutes a great business. And I have written about this for a reason. ALL of the best investors spend their time finding those outstanding businesses, so that when the urge to sell certain stocks overcomes the collective market and people are running for the hills, these Masters can sit comfortably in the knowledge that the deep understanding of those businesses that they own allows them a certain level of reassurance, and they can choose not to sell, or to Sit On Their Ass.

Selling, as explained above, costs more in the long run and requires an adeptness that most of us lack. When the world’s best state that their biggest mistakes were in selling, not buying, you have to take notice. Outperforming the market is almost impossible for the average investor, yet these Masters do it … ‘Sitting On Their Ass.’

Sources:

‘The Art of (Not) Selling’ - by Chris Cerrone. Akre Capital Management. 2019.

‘When to Sell a Great Company’ by Investment Masters Class. 2017.

‘Quality Companies, Compounders and Value Traps’ by Investment Masters Class. 2016.

‘Hold Discipline,’ Lawrence Burns, Baillie Gifford, 2021.

Follow us on Twitter: @mastersinvest

TERMS OF USE: DISCLAIMER

![The Power of Compounding - Warren Buffett vs The Market [Source: Visual Capitalist]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/568cf1da4bf1182258ed49cc/1579556341460-KURIGU5VALX9XGPJ1NRM/compounding.JPG)

![US10yr Bond Yield Vs S&P500 Earnings Yield [Source Bloomberg]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/568cf1da4bf1182258ed49cc/1520921041532-6FFC52F6ZMLWKO5TU0FL/bond_v_spx.JPG)

![US10Year Yield less Inflation [Source Bloomberg]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/568cf1da4bf1182258ed49cc/1520837186222-GGTKCTWUC5ZI1B7XSR6K/cpi_real.JPG)