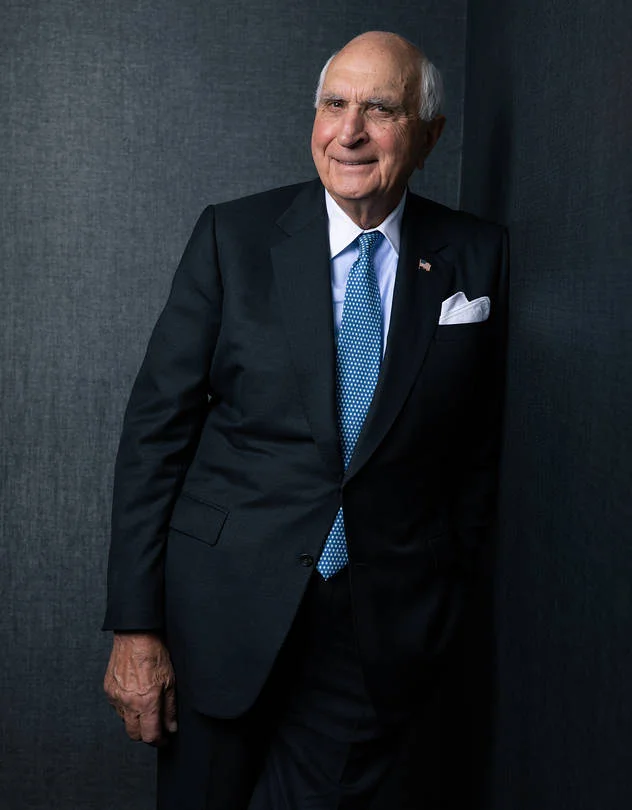

In his third year at a New York hedge fund, Christopher Hohn had a huge year — and they paid him a US$10 million bonus. Most people would call that “making it.” He didn’t.

Hohn says he immediately gave it away — set up a foundation and put the money into it. “I didn’t want it… This isn’t really something I should have.” Then look at what he did next.

When he launched his own firm, he didn’t reach for a predator or fortress name — no Tiger, no Viking, no Citadel. He called it The Children’s Investment Fund. The name wasn’t marketing. It was a statement of intent.

Because to Hohn, money is not identity. Maybe that’s easier to see when you’ve come at the game as an outsider: the son of a car mechanic, raised in a small town — a Jamaican-born father and a legal-secretary mother. It’s not even the endgame. It’s a tool — almost a commodity — and his deeper view is simple: you’re a steward, not an owner. You’re passing capital through your hands. It takes some people a lifetime to see that you can’t take a pin with you.

Chris Hohn’s investing legacy is as striking as his approach to life. Over more than two decades, TCI has compounded at more than 18% a year — roughly nine percentage points ahead of the market. This has been achieved through a holding of around fifteen stocks, with the top ten position sizes generally between 8% and 13%. These aren’t hidden gems — companies nobody has heard of. The majority of the portfolio (c90%) has comprised companies with market capitalisations above $50 billion: names like General Electric, Moody’s, Canadian National, Visa and Microsoft.

With fewer than ten investment professionals, and more than $77b of funds under management, the fund — according to the Financial Times — has generated $68.4bn in cumulative gains for investors after fees since its founding in 2003. In 2025, the fund generated a net return of 27%. According to Forbes, the firm’s latest annual report (as of March 31, 2025) says that for the prior year it donated $797 million to charity, including $637 million to The Children’s Investment Fund Foundation.

What distinguishes Hohn, as an investor, is the severity of his focus: an almost obsessive attention to competition; a quest for multiple, layered barriers to entry; a time horizon measured in decades; and a love of an often underappreciated asset — pricing power. He discards most industries without regret.

Hohn has gravitated toward quality: fewer positions, longer holds, and a hunt for “super-companies” that don’t fade. That persistence is the wrinkle — most models truncate the runway, so the real value in the outer years goes underappreciated. He calls long-termism in a great company a free lunch — the same edge that built the records of Buffett and Munger, Chuck Akre, Nick Sleep, Steve Mandel and David Polen.

He’s also evolved in how he behaves as an owner. There’s a symbiosis with management — constructive, engaged, but not deferential. He cares more about a company’s DNA than any single executive, yet he’s willing to use his position to press for (or block) corporate actions he believes would destroy intrinsic value. Not activism as theatre — ownership as responsibility.

I’ve long admired Hohn. As investors, we can learn plenty from his craft — and maybe even more from his posture: purpose first, money second… capital deployed in service of something that outlasts you.

Having studied many of the world’s greatest investors, his lessons land with the same force whether you’re a newcomer or a veteran. I recently spent a morning revisiting his public interviews and talks, and I’ve collected my favourite extracts [lightly edited for clarity] below.

Risk versus Return

“Investing is all about risk and return — and the vast majority of investors focus on return. You see it with any asset allocator: what’s your return? That’s the only thing. But I focused my career on risk. Return does matter, of course, but to me, risk was always the first thing that mattered.”

“One of the things about our strategy is we actually don’t like risk. We take risk, but we want low-risk businesses that will get our capital back. That’s why we don’t seek the highest return. If we’d invested in Tesla, we’d have been much richer, but it’s a risky company for us. Increasingly, I think of us as a ‘stay rich’ fund because the business models are so strong, and we’re always very focused on valuation as well.”

“Warren Buffett was asked what the definition of risk was. You know what he said? ‘Not knowing what you’re doing.’”

Learning

“Like everyone, we’re always learning.”

“Through engagement, you can learn something. If it’s a one-way conversation — if you’re just speaking at someone — you don’t learn anything. We have to learn.”

Humility

“Be humble. If you become arrogant, that’s a killer in the investing business.”

“We want to hear competing views. We have some members of the team who are inherently bearish, and they’re good for testing the bear case. We always want to hear: how could technology disrupt? Or what could competition do?”

Unconstrained Thinking

“It’s often said that as an immigrant you feel more like an outsider — and outsiders challenge the establishment. Part of my psychological makeup was to think in an unconstrained manner. Harvard Business School taught me there was no reason to assume people were smarter than you.”

Temperament

“Investing isn’t that hard. The hard part of investing is - Warren Buffett said it - temperament. You need the right temperament.”

Keep it Simple

“We keep things very simple. The strategy works.”

Intuition

“Another key point is intuition. We work with intuition. It’s been defined as thinking without thinking, which the Buddhists would call a koan — something that just doesn’t make sense. A lot of people don’t understand what intuition is. It’s sort of the opposite of intellect. Pattern recognition, in a way — you’ve seen it. It’s knowing.

Of course we’ll do analysis, but it’s a higher level of intelligence than just intellect. And it applies to everything: is someone trustworthy or not trustworthy, and the patterns. I wasn’t into intuition so much before the last five to ten years — that’s been a change — but I think I always operated at an intuitive level.”

“Investing’s an industry where you learn from experience—by osmosis—as much as, or more than, from any single mentor.”

Permanent Loss of Capital

“What kills you as an investor is permanent loss of capital.”

What Matters

“It was a spiritual master who once said, very few things matter, and most things don’t matter at all.”

“You need to get out of the noise and just focus on the handful of things that matter.”

Competition and Barriers to Entry

“Competition kills profits. Yep - it’s as simple as that. Substitution eliminates your business.”

“Competition matters because too much competition erodes your profits — and maybe you don’t make any money at all. So I hate competition. Competition makes predictability and valuation impossible. And the interesting thing is: to me, in a sense, competition and disruption are the whole thing.”

“Warren Buffett said most moats aren’t worth a damn — because you think you’ve got a moat, and then it erodes. So the real thing is the sustainability of moats.”

“The fact of the matter is that most investors underestimate the forces of competition and disruption because they underestimate complexity. They look short-term. And so we do two things, really: we look for companies with such high barriers to entry over the long term that we think we can have a reasonable idea they’ll still be around. Okay — we can’t be precise about exactly what they’ll be worth, but they’ll be there not in one, two, or three years, which is the normal time horizon of an investor, but in 20 or 30 years, which is where the value — if you do an NPV model — really is. And so we try to focus all our time on barriers to entry and disruption.”

“It’s all very well to say you’re long-term, but that’s only a good thing if it works. And it only works if you’re right on the first point: the quality of the company and the barriers to entry.”

“We're totally focused on fortress business models, where competition is limited and very difficult and so they have very high barriers to entry. This is the classic Warren Buffet mindset, quality companies.”

“Moats change. We used to love consumer staples, but they became richly priced and offered low returns. We used to like media content companies, but streaming severely weakened their moats. Disruption can happen — you’ve just got to stay alert to it.”

Don’t Sell

“If you’re right — that you’ve found a company that’s going to be a good company long term — then you should hold on to it, because there’s a persistence to the barriers to entry and the things that make it good. So, in simple terms: good companies stay good, and bad companies stay bad.”

“There aren’t that many great companies — the super-companies of the world — and if you find them, you should hold on to them.”

Quality Companies

“Ultimately, the quality of the business trumps everything.”

“We say maybe there's 200 companies that we consider to be high quality and investable.”

“We invest in high quality companies with predictable free cash flow.”

“Here’s the thing: the longer you can look out, if you’ve got a great company, the more value there is.”

“Actually, the compounding of intrinsic value matters more than the stock price. If you have a great company, it will grow intrinsic value. And here’s the thing about multiples: they matter less than the growth when you look at it over a longer period. But most investors are unwilling — or unable — to invest on a long-term time horizon.”

“If you look empirically, it turns out that the very best companies — high ROEs — stay good. They don’t disappear overnight, generally. And bad companies stay bad — low ROEs stay low. There's persistency.”

“The value of [a great] company is only really seen over the long term. They say there’s no free lunch in finance, but I do think long-termism in a great company is a free lunch. Because if you look at any sell-side model, they’ll go out three years — or two years. Why? Because that’s the time horizon of the typical buy-side investor: one or two years. But what if it can keep being good for 30 years? Then you’re completely undervaluing that company. And people don’t look at it because most companies — 95% — are mediocre or bad. They meet their cost of capital, but they’re not super-companies.”

“We’ve become more quality-focused in our choice of companies. When I started, I’d look at anything - banks, miners, steel companies. Over the years I realised there are good companies and bad companies. I became more discerning: good is better. So we’ve become more quality-compounding focused.”

“We’ve gravitated towards quality. We believe what Warren Buffett said: a cheap but questionable business is inferior to a fairly priced, high-quality company -because bad businesses surprise you on the downside, and good businesses on the upside.”

“There are many investors who will buy a company, independent of valuation, as long as it’s a good company, but we won’t.”

Business Focus

“I was always willing to look at the company fundamentals, and not try to guess the stock market - or focus on macro, or trading. I was always fundamental. Most investors are not fundamental. They trade actively. They look at data points. They say, ‘What’s the catalyst?’ They don’t really know what the company does. So I think the fundamental approach has been key.”

Physical assets

“I’ve always liked hard assets — infrastructure — and what comes within that can expand beyond. We’ve owned a lot of airports and toll roads. We found toll roads in Europe, then toll roads in Canada and the U.S., through Ferrovial — and then cell-phone towers, and railroads, and so on.”

“There are many, many moats — and one that most people don’t look at, interestingly, is irreplaceable physical assets. We’re in a world where people just look at earnings. They don’t look at asset value, or physical assets. And so we like quite a bit of infrastructure.”

Network Effects

“We found other barriers to entry, such as network effects. Certain industries — payments is one. We’ve been a shareholder of Visa a long time, where it has this huge, ever-growing network connecting every customer and every bank to the world. And as the network grows, it becomes ever harder to replicate.”

Intellectual Property and Multiple Barriers to Entry

“Aerospace is a sector that we’ve come to learn about and understand, and where the barriers to entry are multiple. Often you would like not just one barrier to entry, but maybe five — intellectual property; brands; hard assets; contracts; network effects. We’ve been big shareholders in aircraft engines, where you have many of those.”

Aircraft Engines and No New Entrants

“One space we like is aircraft engines. It’s a very complicated product because of the materials complexity — the engines run at such high temperatures that metals melt — and so many different things have to come together. Thousands and thousands of complex parts.

So that’s a business where there are only two players in narrow-body engines and two in wide-body, and there’s been no new entrant for more than 50 years. The last new entrant was GE — and that tells you something. It’s a big industry, but it’s so complex, and very hard to enter.”

Installed base

“Installed base is another barrier to entry — where customers can’t switch, because of regulatory switching costs. And so we’ve expanded into other areas: rating agencies is another one.”

Regulatory Risks

“[In a regulated business] regulators may come knocking on your door. Every case is different. And the ideal case is that there is competition but weak competition and apparent competition… An example: you might look at Heathrow Airport and think, ‘Oh, that airport is fully regulated — airports can’t be good.’ But if you look into the detail of AENA, it’s a different animal. It has a piece that’s regulated, and a much bigger piece — 70% of value, maybe more — that’s unregulated. So maybe the regulated business gives you a bond-like return of 7%, but the unregulated piece can give you a much higher return.”

Pricing Power / Under the Radar

“If you really do find one of these super-companies that can dominate their industries, they have something special: pricing power — which is a rare thing. Most companies don’t like to talk about it. And it’s a special thing because it means you can grow more than your volume. It has a leveraged effect: if you can price above inflation — that’s what pricing power is — there’s no cost to that. And if you have a 10% margin, every one point of real pricing power is massive.”

“Growth can come from two forms: price and volume. And most companies don’t have pricing power. They can only price — if they’re lucky — at inflation, and that’s why people don’t focus on it. They don’t even look at where growth comes from; they just assume it’s volume plus inflation. But there is a special group of super-companies that can price above inflation — and that’s, as Buffett taught, the test of whether you have the moat. Real pricing power above inflation can be very valuable, because if you can price 1% above inflation and you have a 20% profit margin, your profits will grow 5% faster than revenue. People don’t go into it or analyze it because there are so few companies that have it — but it’s something a lot of our investments have.”

“How do we know if a business model is really strong? Well, there were some clues given by the investment genius Warren Buffett. He said a really strong business has pricing power. It can raise prices above inflation—meaningfully above inflation.”

Obvious Ideas

“You really want something that’s obvious. Warren Buffett used to talk about this: when it’s not obvious, you probably just leave it alone, because it’s probably not sustainable. So it’s sustainable barriers to entry.”

“If we own an airport, it’s pretty obvious. We own a company that owns all the airports in Spain — we’ve owned it for a decade. I was on the board. No one’s ever going to rebuild those and overbuild you. And 75% is unregulated. Or toll roads where you have 100-year duration, or 60 years. We don’t know whether people will drive electric cars, or which brand of electric car — but it’s pretty clear they’re going to need these roads. So those are obvious things.”

Essential Need

“You need something that’s essential, so you’ve got to be confident of the need. Are people still going to want to fly? We believe that’s a durable need.”

“We don’t like discretionary things. I’ve never been an investor in the handbag business. Lots of people have, and they’ve made lots of money in it. But I’ve never understood what makes one handbag better than another — or why it’s essential. So anyway, it may well be I don’t need to understand everything. Stay within your sphere of competence. That’s what Buffett said.”

“What’s most important for us is something slightly different [than recurring revenue]: an essential product or service. We don’t like things that are discretionary.”

Growth

“Depending on valuation, you don’t necessarily require a fast rate of growth. And growth can come in two forms — volume and price — so you have to break it down.”

“If you have low volume growth but a lot of pricing growth, that’s actually more important because of the leveraged effect — there’s no cost associated with it.”

“A lot of investors get confused and think the thing you want is growth. If you look at industries like airlines, they’ve been growing for 100 years — maybe 5% a year — fantastic growth. But collectively and cumulatively, the industry never made any money because competition was too strong.

So growth per se — growth by itself — is not a guarantee of making money. You need, critically, barriers to entry and protection from competition, and sustainable value-add — high value-add — that you can charge for. It’s really the combination of barriers to entry and high value added. And of course, then growth has value.”

Management

“Does management matter? Somewhat — it’s not the key thing. A great manager in a bad business can’t necessarily do much. So I think focusing on trying to assess management through conversation may miss the point. You may overstate the value of management. And sometimes management won’t even necessarily understand their own pricing power — and their latent pricing power.”

Disruption is Rising

“I think the world is changing so much that some of these apparent moats are being beaten down by AI and other disruptive forces. So the forces of disruption, I would say, are actually rising.”

Company Relationships and Activism

“Today our relationships are generally very, very constructive with companies - but it wasn't always that way.”

“I've learned that actually activism, hardcore activism, is not a great thing.”

“We act as owners. We always act as owners. What does that mean? We’re interested. We’re engaged. We think we have a right to appoint directors — we have a legal right to it. And one thing we’ve learned is: governance does matter.”

Incumbency / Large Companies

“I do think the very best companies in the world are public companies - not every one, but generally. And one of the reasons is, in many industries, scale and scope matter. Small is not beautiful.”

“There’s a lot of power in incumbency. This is another important point. Take a company like Microsoft, which we’ve invested in. One of the barriers to entry is bundling — because it creates customer switching costs.

What do I mean by this? The Office franchise, which we’re all familiar with, has many products in it: word processing, Excel, email, security — different things — and they sell it as a bundle. They don’t disaggregate it. And when a new product, or a potential competitor, enters, they can add it to the bundle.

So Zoom came out with video conferencing, and Microsoft had to respond. They launched Teams, and they were able to distribute it through the bundle — effectively free to everybody. And even though Zoom, some people believe, was a better product — or is a better product — Microsoft won that battle because they had the installed base, the incumbency, and high switching costs. Once people are using their Office software, they don’t want to switch.

And so people started using Teams — something given to you free. Why? Because it was good enough. It didn’t have to be the best if it’s free.”

Industries to Avoid

“We don’t like banks — the low quality of earnings — because they’re very leveraged, and much more than people think. People look at equity to risk-weighted assets, but what matters is equity to total assets. Many banks have been run at 100 times. And, two, they’re opaque. You can’t really look into the balance sheet from the annual accounts.”

“The other reason with banks is very important: sooner or later, you may find someone without a lot of intelligence comes to run them — and then it can be toxic. People go for growth — Anglo Irish Bank, if you remember that one — and they can destroy shareholders. Bonuses, you know. Bear Stearns — you know. Non-alignment of interests, with leverage and opacity.”

“The auto industry is obviously a commodity, retail, insurance, commodities, commodity manufacturing, tobacco, the truth is, anything in most things in manufacturing - most industries.”

“I’ll list you a couple more [bad industries]: traditional asset managers — bad businesses. Fossil fuel. Utilities — bad businesses. Airlines — bad businesses. Wireless, telecom — bad businesses. We think media is bad. Advertising agencies. It’s a very long list. Why? Because it’s competitive — with existing players and new technologies.”

“Certain industries are more prone to disruption than others. Your risk is much higher. So we try to avoid those sectors — because you’re asking for trouble — or limit our exposure. And one of those sectors is technology.”

“We have figured out a lot of industries which have these high and sustainable barriers to entry and we pretty much ignore all other industries. We focus on a limited number of industries that we really understand, that we’ve done decades of work on, and we research them in great depth. Once we’re convinced, we stick with them long term. And so we don’t need hundreds of ideas.”

Shorting

“At a high level, we learned that shorting isn’t a great business — because you can be right, but not be able to hold it, or fund the losses.”

“I’ve never really been a significant short-seller. I don’t think I’ve cumulatively made absolute money in it. And I sort of agree with what Warren Buffett told me one night. I had dinner with him, and I asked him about shorting, and he said he didn’t do it because he and Charlie Munger concluded it was just too hard — too unpredictable.

He thought long and hard about it, because in shorting you need to also understand investor psychology.

When the short goes against you, you have to fund the losses. People think that’s a costless thing, but you have to sell longs to fund the losses on shorts. And you can eventually be right — but can you hold your position? It’s a very hard thing, and you could be squeezed.”

“I never really believed in the long/short model. We’ve been substantively long. We’ve had shorts periodically, but they’ve generally been 0% to 20% in aggregate. They’ve underperformed markets, so they’ve added alpha, if you like, but not absolute dollars. One of the big advantages of being long is you can collect carry. By carry, I mean the natural intrinsic value underlying the security—whatever that number is, 10%, 20%—you’ve got that tailwind. When you’re short, you have to be right on timing, which is a bet on investor psychology, and it’s much more difficult. You also have asymmetrical risk/reward. So the logic of shorting never really made sense. I think a lot of funds do it to justify a high fee structure, or because investors expect it of them.”

Portfolio Concentration and Position Sizes

“Another thing we’ve done is concentration. We’ve owned a few things. We may have 10% type holdings — 10 stocks, 15 stocks. We don’t own 100 things.”

“We’ve used concentration to great advantage. But, of course, it’s a double-edged sword, and you shouldn’t use it if you don’t have that level of conviction. If there are times where you don’t, then be diversified. It only makes sense where you have outsized risk/rewards and conviction. That’s our formula, if you like, for how we size positions. We size them as a function of risk/reward and conviction.”

“We think about concentration as an important way to add value to our process. It was George Soros who said, “It doesn’t matter if you are right or if you’re wrong in investing — all that matters is how big you are when you’re right and how big you are when you’re wrong.” That’s so logical, but most people can’t develop conviction and they have extreme diversification.”

Long term / Portfolio Turnover

“Long termism is key.”

“Taking a long term view gives us a time horizon arbitrage.”

“I think the key for us is to mantain our core philosophy of long-term investing. As long as we still believe in our position, we won't let the markets change our mind."

“Long-termism. You can find a great company, but if your time horizon is very short, you’re at the mercy of the vagaries of what Keynes called the voting machine. He said: in the short term, the market is a voting machine — and only in the long term is it a weighing machine.”

“The average holding period of our current portfolio is eight years. I'm not saying that's the limit. Some we've held for 13 years, but it could be 10. It could be 20.”

“I like things that will just compound long term. I don’t change year to year very much. Things that I feel confident will be around in 30 years, in a dominant position, excite me — because it’s predictable. I value predictability.

Most investors are looking for the next hot thing — the new thing.

And sometimes I’ll say, a bit sarcastically: do you need to change your wife every year? You wouldn’t ask that question because you’re happy with her. It’s not that easy to find the right partner. It’s not that easy to find the right investment. So why do you want to change them immediately?

If you find something good — and it’s going to be good long term — stick with it, and don’t assume newer is always better.

Investors don’t think about sustainability. They want the next hot thing. So many people think in terms of what Benjamin Graham said: in the short term, the market is a voting machine. What’s hot? What’s new? But in the long term, it’s a weighing machine.

In Covid, Peloton was hot. It went to a $50 billion valuation. Everyone was on their Peloton machine. It virtually went to zero.

That’s the most important question. We’re more interested in: what’s going to be around — rather than what’s new?”

“We’re not churning our portfolio on a daily basis like many funds. We might hold a stock five years, ten years. One of the important parts of our strategy is we’re long-termists. We really believe in the power of not trading, low turnover, and just buy and hold - as long as the company is delivering and the business model isn’t at risk of disruption.”

When to Sell

“[Sell] when your view is that the intrinsic value is not as good as other things — not just value, but conviction. So the philosophy has two components, if you like. First: intrinsic value — the price still has to be at or below intrinsic value. But there’s a second point, which isn’t really focused on by many investors: conviction.”

Public versus Private Equity

“Like everything, there are pros and cons with private equity — arguments for and against. But in private equity, you pay a price for control. You pay a premium — and it can be big. Don’t get me wrong: control has value. It has a value. But is it worth 40% — or whatever premium you have to pay in a competitive auction? In public markets, there’s an offer every day. You can take it or leave it. So I just think that point is relevant: entry price matters.”

“If you're wrong in private, there's no way out, in the short term. And if you're wrong in a public you have a chance to get out. You have a chance.”

The Inner Life

“I’m very interested in the spiritual world—that’s another major passion. I’m not religious, but spiritual. I meditate on a regular basis. And I like nature. I like going into nature and stilling the mind. Those are my other passions.”

Reading

“I like reading.”

“I like the biography of Warren Buffett, The Snowball. I think that’s a great book on his life. Books on some of the great icons - Jean-Marie Eveillard from First Eagle. Books on George Soros - The Alchemy of Finance and reflexivity. Seth Klarman’s early work. Outliers is a good book. Joel Greenblatt’s book - there are many. Poor Charlie’s Almanack about Charlie Munger - that’s quite a good one too.”

Purpose Through Philanthropy

“When I was 20 years old, I met children living in extreme poverty for the first time. Like all children, they were precious – but the circumstances around them, the system they had been born into, had taken opportunities away from them. At that moment, I made a commitment: if I ever had the resources, I would work to address the barriers that prevent children from living healthy, happy lives. This commitment has driven every aspect of my career.”

“I don't really care about money, other than its value in helping people.”

“For me, I could never find any purpose or meaning in my life except service. That’s something that comes from within — and that’s the origin of my philanthropy.”

“I always had more pleasure and meaning from philanthropy than from consumption.”

“I know so many wealthy people in my industry—very unhappy. I’ve always found fulfillment and meaning from the service side.”

“My first love was always children because you can see the purity of the soul so much more clearly in a child. But my whole life is to serve humanity in whatever form is needed: health, education, child protection — and also climate change.”

“We have about six and a half billion dollars in the foundation, and I also do philanthropy outside of that. And so between us, we're giving away over $500 million a year two main areas, climate change and children's health in Africa and India on the health side, we focus on foundational issues.”

“This concept that we own things — I’ve always thought, actually, I don’t own anything. I’m just a custodian. It’s money. Mine needs to be given away, and put in service to humanity.

And if you go out of the intellect into intuition — which is what made me give away that money — then, when we’re on our deathbed, I don’t think we think we own things. And why would we? Because, ultimately, everything is a gift.

I didn’t make all this money because I was smart — or lucky. I think it’s because I’m willing to give it away. And I think the most important thing, back to what matters, is consciousness and love. If we connect to that, we’ll find purpose.

And so, for me, in a nutshell: philanthropy has given me purpose.”

Life Lessons

“Follow your passion. Life is too short not to enjoy every day. Find out who you are - discover who you are - self-analysis. People think life is about doing things - what you achieve - but that’s wrong. The real secret of life is who you become. Figure out who you want to become, not what you want to do. At the end of life, nobody focuses on what they did - it’s who they were.”

Summary

In the end, Hohn’s edge isn’t a secret screen or a clever trade. It’s a philosophy — and a filter.

Hohn’s worldview is a set of preferences: simplicity over complexity; risk-first, not return-first; long-term over short-term; business over management; fundamentals over macro; price growth over volume; dominance over competition; essential over discretionary; quality over cheap.

It’s also patience over activity; large companies over small; intuition over intellect — with concentration over diversification, a few industries over many, and multiple moats over a single moat.

From there, the craft follows: own a dozen or so great businesses; demand durable barriers; respect pricing power; hold for years; stay humble; keep learning.

But beneath the craft is something rarer: a view that capital is stewardship, not identity — and that the point isn’t just to compound money, but to compound meaning.

As Hohn put it:

“And there are many paths to connect to it… Through suffering, you eventually come to learn that the spiritual world is not just real, but it’s the whole thing… and that’s the only source of real purpose and meaning and joy… And I think that if you crack that, then everything else is easy.”

Sources:

‘The Children Are Our Future with Sir Chris Hohn,’ FEG Insight Bridge, 2025.

‘Sir Chris Hohn: The Full Interview,’ Money Maze Podcast, 2021.

‘Investing & Philanthropy - with Sir Chris Hohn,’ Money Maze Podcast, 2025.

‘Sir Chris Hohn - In Good Company,’ Nicolai Tangen, Norges Bank Investment Management, 2025.

‘Letter #280: Chris Hohn and Christian Sinding,’ Kevin Gee, 2025.

‘Sir Chris Hohn Transcript,’ Iceman Capital, 2025.

‘Founders Message: Sir Christopher Hohn,’ The Children’s Investment Fund Foundation.

‘Activist Investing Creates Inefficiencies — and Opportunities,’ Institutional Investor, 2014.

Further Reading:

‘Beyond Investing.’ Investment Masters Class, 2021.

Follow us on Twitter : @mastersinvest

* Visit the Blog Archive *

TERMS OF USE: DISCLAIMER