We’re all looking for great businesses to invest in. Those companies that seem to defy the natural order; that succeed in industries or sectors where others quite simply, don’t. They each have a difference, an advantage over their competitors which is quite often something so simple that it leaves others wondering why they hadn’t thought of it themselves.

It doesn’t sound like rocket science, and often it’s not; it could be a combination of lots of little things producing results that defy the incremental benefits. Often the results are non-linear; one plus one equals more than two. It’s something Charlie Munger refers to as Lollapalooza effects.

“Really big effects, lollapalooza effects, will often come only from large combinations of factors.” Charlie Munger

A few years ago I met with the CFO of a highly successful national furniture chain. This family business had achieved financial metrics that defied its industry; returns on equity consistently above 50%, gross margins above 60% and payback on new stores of under six months. Quizzing the CFO I asked, “Should the economy turn down, you could always cut margins a little?” To which he replied, “No, you don’t understand how the business works.” Expanding a little further, “The CEO starts with the 60%+ margins and works backwards. That’s the goal. A two hundred dollar chair is a two hundred dollar chair. Price it at two-hundred and fifty dollars and you won’t sell any. The CEO does the buying (how many other furniture store CEO’s do?) The CEO works with the suppliers to deliver that chair at a price that allows a 60%+ margin. It might mean removing the number of buttons, changing the fabric or redesigning the chair a little to get that outcome. It’s not about dropping price.” Wow, I thought to myself, that’s the silver bullet. That’s what makes this business so successful. A few months later I had the opportunity to ask the CEO directly, “What’s the key to success? Is it in the sourcing of product?,” I asked. Expecting confirmation of the silver bullet I’d uncovered, he replied, “yes that’s one thing, but really it’s the fact we do lots of little things a little better.”

This combination of factors often creates an impenetrable barrier for competitors. Polen Capital’s Jeff Mueller touched on this in a recent Columbia Business School podcast:

“There’s this song by Blink 182 called ‘All the Small Things’. For some reason when I think about competitive advantages it pops into my head. The best compounders I’ve studied and the best ones we’ve invested in don’t just have one competitive advantage where you point to it and say ‘yep, that’s it’. They usually have built this mosaic pulling from almost all the competitive advantages; they have networks, and a great culture, and a safe or aspirational brand and also economies of scale. When you get a lot of these working in the same direction it makes the companies almost impossible to really compete with out in the market place.” Jeff Mueller

Such firms are often more predictable businesses than firms which rely on a single competitive advantage (e.g. a patent).

"There is no a priori reason why a comparative advantage should be one big thing, any more than many smaller things. Indeed an interlocking, self-reinforcing network of small actions may be more successful than one big thing… Firms that have a process to do many things a little better than their rivals may be less risky than firms that do one thing right [e.g. develop/own a patent] because their future success is more predictable. They are simply harder to beat. And if they’re harder to beat then they may be very valuable businesses indeed." Nick Sleep

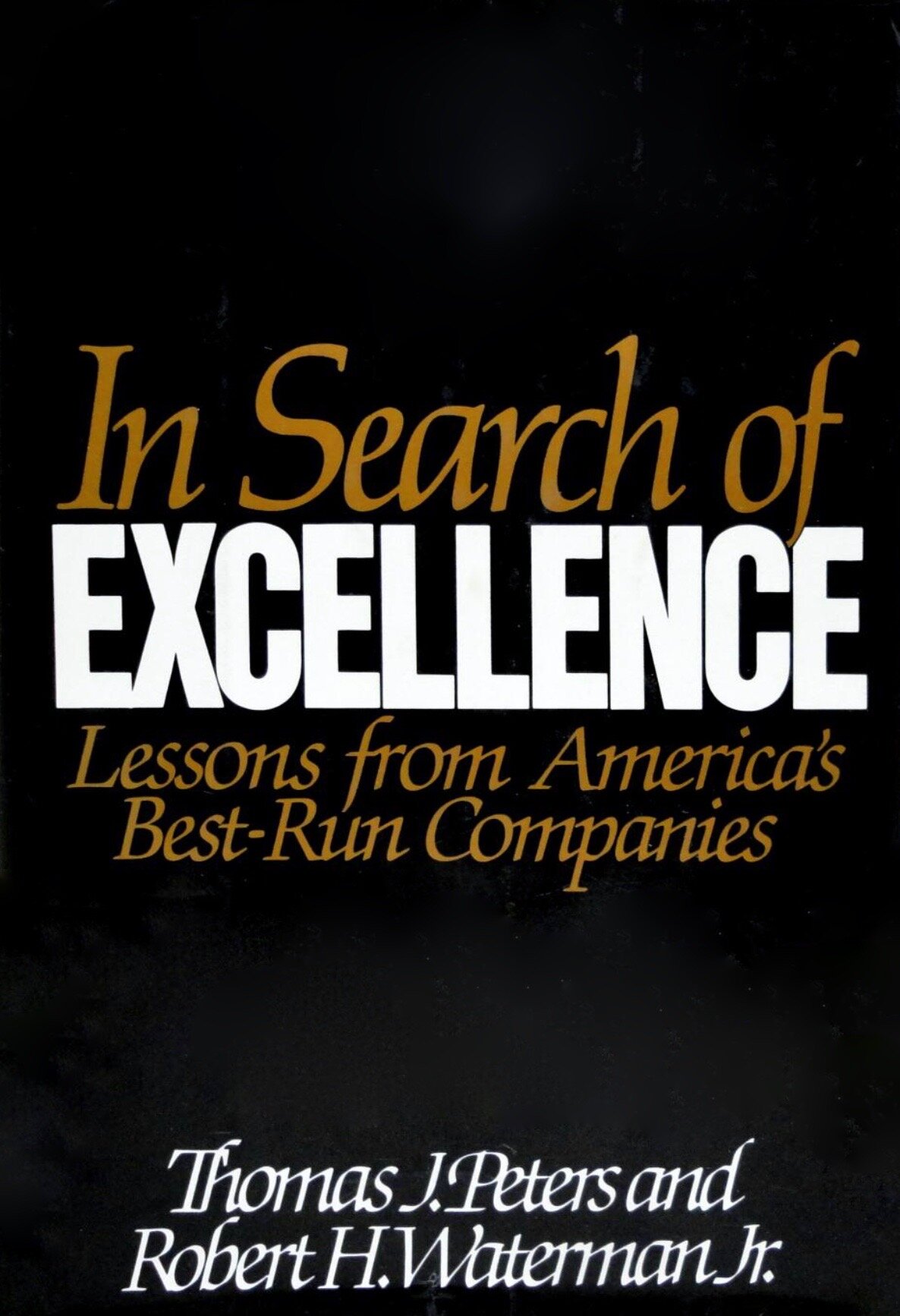

In the book, ‘In Search of Excellence - Lessons from America’s Best Run Companies’, McKinsey alumni Thomas Peters & Robert Waterman identified a number of ‘strikingly similar themes’ that characterised the excellent companies they’d researched. It was a combination of these that accounted for the outperformance:

“The most important notion, as we’ve said time and again, is that there aren’t any one or two things that make it all work. [It can be] a dozen factors. And it’s all of them functioning in concert.”

Despite almost four decades passing since the book’s publication, the themes are as relevant today as they were then. Little wonder the book has been accredited by Warren Buffett as, “A landmark book, without question the most important and useful book on what makes organisations effective, ever written.”

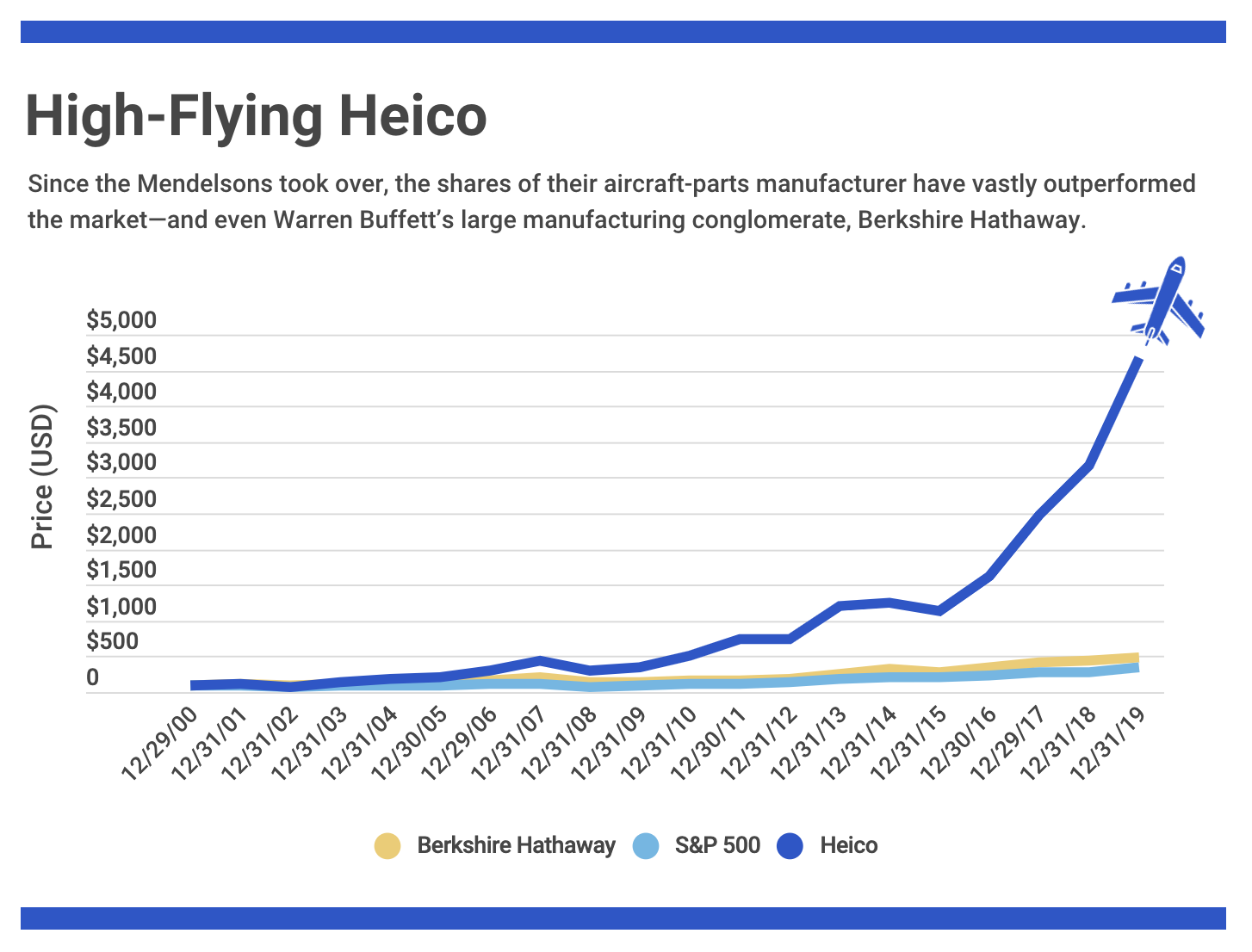

I was reminded of this concept recently when reading a Forbes article about an aircraft parts manufacturer called Heico. The title certainly grabbed my attention, ‘The 47,500% Return: Meet The Billionaire Family Behind The Hottest Stock Of The Past 30 Years”. I couldn’t help but notice many of the factors that had surfaced in Thomas Peters and Robert Waterman’s research.

I’ve extracted a selection of the more interesting comments from the Heico article complemented by a few other sources, and where relevant, provided extracts from ‘In Search of Excellence' [ISOE].

Family Business:

HEICO: “I mean, it’s hard to envision family businesses that have been this successful for this long.”

ISOE: “Many of the best companies really do view themselves as an extended family.”

Culture:

HEICO: “Our culture is what ultimately drives the bottom line.”

ISOE: “The excellent companies are marked by very strong cultures.”

ISOE: “Without exception, the dominance and coherence of culture proved to be an essential quality of the excellent companies.”

Focus on the Customer:

HEICO: “We believe that the customer is the most important person in our overall organization. So we are here to serve the customer. And we pride ourselves on making good profits but not gouging the customer in terms of pricing.”

HEICO: “Our customers are our highest priority. After all, without customers, we have no business.”

ISOE: “Whether bending tin, frying hamburgers, or providing rooms for rent, virtually all of the excellent companies had, it seemed, defined themselves as de facto services businesses. Customers reign supreme.”

Close to The Customer:

HEICO: “Typically, our new products are designed in response to direct customer specifications or requests, not as general concepts offered for sale which we hope will later be purchased. This allows us to have a laser-sharp focus on our exact customer requirements.”

HEICO: “Our approach has been, and will continue to be, to learn from our customers what they need, not to develop products and then try to convince our customers to buy the products.”

ISOE - “The excellent companies are better listeners. They get a benefit from market closeness. Most of the real innovation comes from the market. The best companies are pushed around by their customers and they love it.”

ISOE: “The excellent companies pay close attention to what customers want. From listening. From inviting the customer into the company. The customer is truly in a partnership with the effective companies and vice versa. Successful firms understand user needs better. Successful innovations have fewer problems.”

Cheap Prices:

HEICO: “They have done so by acquiring 78 companies over the years and by pricing their parts cheaply.”

Diversified Products / Customers:

HEICO: “Heico produced nearly 100,000 parts, sold to nearly every major airline in the world, as well as defence customers like the U.S. government.”

Wrong Incentives:

HEICO: “The board [of the original Heico company] owned nothing—owned no shares,” recalls Larry. “They weren’t motivated.”

Barriers To Entry:

HEICO: “They found [the after-parts market] to be particularly alluring. Everything needed Federal Aviation Administration approval, which ensured that not every Tom, Dick and Larry could easily enter the industry.”

But Not Too Many Barriers:

HEICO: “Replacement parts weren’t generally patent-protected, so all the Mendelsons had to do was reverse engineer them, then prove to the FAA that they were up to snuff.”

ISOE: “The so-called high tech companies are not, first and foremost, the leaders in technology. They are in high tech businesses, but their main attribute is reliable, high value-added products and services for their customers.”

Win-Win:

HEICO: “Among our greatest strengths over the past five decades is our emphasis on building relationships — relationships with team members, customers, suppliers, shareholders and other stakeholders.”

ISOE: “We have a host of big American companies that are doing it right from the standpoint of all their constituents - customers, employees, shareholders, and the public at large. They’ve been doing it right for years.”

Product Quality Critical:

HEICO: “We do a full metallurgical inspection on every single lot of parts we produce. That includes material hardness, grain size, grain-flow structure, coatings. . . . The reason we do it is because we can’t afford to have a failure.”

ISOE: “Raychem sells complicated ‘smart’ electrical connectors… They sell their connectors on the basis of high economic value of the product to the customer… The connectors are a microscopic fraction of the value of the eventual product - for example, large aircraft; therefore , the customer can, in fact, afford to pay a bundle.”

ISOE: “Quality Obsession. Many of our excellent companies are obsessed by service. At least as many act the same way over quality and reliability.”

Social Proof:

HEICO: “Lufthansa’s investment in Heico—a tacit stamp of approval.”

Investment in Price-Giveback / ‘Jam Tomorrow’:

HEICO: “As their business gained altitude, Larry insisted they live by a blunt rule: “We don’t try to screw the customer.” Heico keeps its prices locked between a third to a half off what an original manufacturer would charge. Heico’s net margin hovers around 15%. It could be more than that if the Mendelsons pushed harder (and some defence products are more profitable). “They’ve historically been reluctant to print a margin over 20%,” says Hebert, the Canaccord Genuity analyst. “They never want to be perceived as gouging or excessively profiting from their airlines.”

HEICO: “Heico’s low-cost, high reliability solutions save each of our airline partners an average of $25m annually.”

Acquire Cost Conscious Founder Businesses:

HEICO: “The Mendelsons are shrewd buyers themselves, having in 2019 completed seven more acquisitions. They shop for owners or top executives who resemble them. “The companies we buy are very entrepreneurial—entrepreneurs that started years ago, started businesses in their garages,” says Larry. “They started with nothing,” which, he says, means “they watch every nickel.”

ISOE: “A few companies have thrived on growth via acquisition, but via a ‘small is beautiful’ strategy. They don’t believe, apparently, in the oft-cited wisdom that ‘A $500 million acquisition is no tougher to assimilate than a $50 million one, so make one deal instead of ten.”

Proper Incentives / Alignment:

HEICO: “The Mendelsons don’t usually buy an entire firm. More often than not, they leave a fifth of it in the hands of the owners or the chief executives running the place to keep them incentivized.”

Incumbents Won’t Compete:

HEICO: “The Mendelsons have been able to earn a foothold in an industry dominated by the so-called original equipment manufacturers, the GEs and Boeings of the world, who are the first to develop the parts and keep prices high on any replacements to help recoup the original R&D costs.”

Innovate:

HEICO: “One of our key tenets is that we must constantly develop, produce and sell new products to add to our existing product lines. Simply put, we are not interested in having our existing businesses remain static.”

ISOE: “There are some associated rules. For example, each division [at 3M] has an ironclad requirement that at least 25 percent of sales must be derived from products that did not exist five years ago.”

Stick to the Knitting:

HEICO: “It wasn’t long before they were casting about for similar opportunities in the after-parts market, which they found to be particularly alluring.”

ISOE: “Our principal finding is clear and simple. Organisations that do branch out (whether by acquisition or internal diversification) but stick very close to their knitting outperform the others.”

ISOE: “Acquisitions followed a simple rule. They have been small businesses that could be readily assimilated without changing the character of the acquiring organization. And small enough so that if there is a failure, the company can divest or write it off without substantial financial damage.”

Source: Forbes

Decentralise / Autonomy

HEICO: “As long as you do what you say you’re going to do, they”—the Mendelsons—“leave you alone,” Barnes says. “And they ask, ‘Do you need anything?’”

HEICO: “We understand that entrepreneurs have unique skills and that they focus on their businesses in critical ways; we generally go to great lengths to avoid losing that. This entails greater autonomy for the businesses than many large companies are willing to give, and an aversion to consolidating acquired companies, but we are committed to this model.”

ISOE: “If the manager of a business can control all aspects of his business it will run a lot better. We believe a lot of the efficiencies you are supposed to get from economies of scale are not real at all. They are elusive.”

ISOE: Regardless of industry or apparent scale needs, virtually all of the companies we talked to placed high value on pushing authority far down the line, and on preserving and maximising practical autonomy for large numbers of people.”

Value Employees

HEICO: “We feel very good about the way that we are taking care of our team members. Some organisations say their people are employees; we prefer to say team members.”

ISOE: “Most impressive of all the language characteristics in the excellent companies are the phrases that upgrade the status of the individual employee. Again, we know it sounds corny, but words like Associate (Wal-mart), Crew Member (McDonald’s) and Cast Member (Disney) describe the very special importance of individuals in the excellent companies.”

ISOE: “Treating people - not money, machines, or minds - as the natural resource may be the key to it all.”

Encourage Ownership:

HEICO: “The Mendelsons have long encouraged their employees to take advantage of a lucrative retirement plan. They match up to 5% of what workers sock away in their 401(k)s—not in cash but in Heico stock. So, put in $5,000, get $5,000 worth of Heico shares, which, of course, have done nothing in the past 29 years but wildly appreciate. In other words, the stock has turned a lot of ordinary Heiconians, especially early staffers, into millionaires. No, that’s incorrect, Larry says. “Multimillionaires.”

HEICO: “The people who work in the company: the machine operators, the secretary, shipping clerks, floor sweepers, cleaning people - anybody associated with HEICO who is on the payroll, is eligible for that 5% match.”

Head Office:

HEICO: “Our corporate head office consists of only six people.”

ISOE: “Top level staffs are lean; it is not uncommon to find corporate staff of fewer than 100 people running multi-billion dollar enterprises.”

Long-Term:

HEICO: “When we came to this company 33 years ago, we decided we wanted to build something for the long term, and it wasn't going to be built for years or a single decade, it was going to be built for multiple decades. And frankly, every single thing that we've done and every decision that we take has been designed to drive sustained long-term growth of the business as opposed to any short-term focus. So when we've got to make decisions on everything from inventory, capital expenditures, people, customer relationships, everything is focused on cash generation as a result of also maintaining low debt, and being able to create a culture which drives long-term performance.”

HEICO: “The thing that's interesting is, I think that these margins are a result of frankly what we did a decade and two decades ago. They're not as a result of what we've done in the last year or two. When you treat your customers right, you treat your people right, you get into a virtuous cycle and I think that's very much where we are. And I think, we're reaping the benefits of the long-term culture that we put into place over 20 years ago, 30 years ago and that's what's driving these numbers.”

Summary

There’s a plethora of useful mental models in the above:

Industry Structure [Incumbents don’t discount so they can recoup previous R&D expense] / Small Cost of Product vs Total Cost / Fragmented Customers / Fragmented Products / Mission Critical - Quality Products / Barrier to Entry [ie FAA Approval] / Reputational Advantage / Pricing Power / Investment-in-Price-Giveback / Decentralisation - Autonomy / Innovation / Close To The Customer / Encourage Ownership / Sensible - Smaller Acquisitions / Aligned Management / Minimal Headquarters - Valued Staff

These attributes together create a formidable ‘Barrier to Entry’ for Heico.

Perhaps, unsurprisingly, you’ll notice that many of the same attributes above are also evident in the great companies covered in these pages before. The majority of these are qualitative in nature - you won’t find them in a spreadsheet.

“Economists talk about ‘barriers to entry,’ what it takes to compete in an industry. As is so often the case, the rational model leads us to get ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ mixed up on this one, too. We usually think of principal barriers to entry as concrete and metal - the investment cost of building the bellwether plant capacity addition. We have come to think, on the basis of the excellent companies data however, that that’s usually dead wrong. The real barrier to entry are the 75-year investment in getting hundreds of thousands to live service, quality, and customer problem solving at IBM, or the 150-year investment in quality at P&G. These are the truly insuperable ‘barriers to entry', based on people capital tied up in ironclad traditions of service, reliability, and quality.” ISOE

While we haven’t covered all the useful mental models from ‘In Search of Excellence’ we’ve ticked off a lot of them. By studying the characteristics that have made businesses excellent, we can then search these out in other potential investments. When a multitude of factors create an impenetrable barrier, a Lollapalooza effect could be in the making - but don’t just look for that single silver bullet; it might just be made up by a lot of little things.

Sources: Forbes - ‘The 47,500% Return: Meet The Billionaire Family Behind The Hottest Stock Of The Past 30 Years’. Abram Brown. January 2020.

‘In Search of Excellence - Lessons from America’s Best-Run Companies’. Harper & Row Publishers. 1983

Follow us on Twitter: @mastersinvest

TERMS OF USE: DISCLAIMER

![Charles Schwab vs S&P500 - 1987-2020 [Source: Bloomberg]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/568cf1da4bf1182258ed49cc/1586424842104-G0A4G1W2N1WOXO00MSLU/Screen+Shot+2020-04-09+at+7.30.33+pm.png)

![The Power of Compounding - Warren Buffett vs The Market [Source: Visual Capitalist]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/568cf1da4bf1182258ed49cc/1579556341460-KURIGU5VALX9XGPJ1NRM/compounding.JPG)

![Starbucks Vs S&P500 (normalised) 2000-2020 [source:Bloomberg]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/568cf1da4bf1182258ed49cc/1578284000658-O70N6HBF3TLNJE6QNDIC/sbux.JPG)

![Costco vs S&P500 - Normalised [Source: Bloomberg]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/568cf1da4bf1182258ed49cc/1570482284970-PB6B5FPRCVIYOOCB21Y2/costco1.JPG)

![Costco vs Walmart vs S&P500 - 2004 - 2019 [Source Bloomberg]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/568cf1da4bf1182258ed49cc/1570599268676-WW5Q0LEY3OUATLD5484R/costco2.JPG)

![BHP RIO Share Price Ratio [Source: Bloomberg]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/568cf1da4bf1182258ed49cc/1559102957215-5I7SM5J8AIJQ19QT5BJ6/bhp_rio.JPG)