There's lots of ways to think about value. When I studied property valuation at university we were taught that value was, ‘the estimated amount for which a property should exchange on the date of valuation between a willing buyer and a willing seller in an arm’s-length transaction after proper marketing wherein the parties had each acted knowledgeably, prudently, and without compulsion.’

Unfortunately, in the stock market there is no one-size-fits-all definition of value. It's worth focusing on market value, intrinsic value and private value.

Intrinsic value, also referred to as underlying or business value, reflects a company's worth and is probably most closely aligned with the definition of value in the opening paragraph. A company is worth the discounted value of the future cash flows an owner will receive. The Investment Masters focus on the free cash flows coming out of the business rather than earnings.

"In reality, earnings can be as pliable as putty when a charlatan heads the company reporting them" Warren Buffett

"Cash flow, not reported earnings, is what determines long-term value" William Thorndike

An investor forgoes capital today to achieve higher returns in the future. While a company's shares can theoretically trade at any price, a company is not worth more than the value of those discounted cash flows.

“Intrinsic value, is in its simplest form the discounted present value of future cash flows” Frank Martin

"Intrinsic value is the number, that if you were all knowing about the future and you could predict all the cash a business would give you between now and judgement day, discounted at the proper discount rate, that number is what the intrinsic value of the business is. In other words, the only reason for making an investment and laying out money now is to get back more money later on. That's what investing is all about. When you look at a bond it's very easy to tell what you get back, it says it right on the bond, it says when you get the interest payments and the principal. The cashflows are printed on the bond, the cash flows aren't printed on the stock certificate. That's the job of the analyst, to change that stock certificate, to change that into a bond. To say that's what I think it will pay out in the future." Warren Buffett

“Bear in mind - this is a critical fact often ignored - that investors as a whole cannot get anything out of their businesses except what the businesses earn. Sure, you and I can sell each other stocks at higher and higher prices.” Warren Buffett

“Occasionally, people lose track of the fact that in the long run, shares can’t do much better than the companies that issue them.” Howard Marks

Those cash flows will be received in the future and the future is unknown. Some company's cash flows are simpler to estimate like a REIT with contracted lease payments while other company's cash flows are much harder to forecast such as a new technology venture. As future cash flows are uncertain it's impossible to ascertain a precise value for what a company is worth. Therefore an estimate of a company's worth is a range and not a single figure. In cases such as technology it may not be possible to estimate future cash flows which significantly raises the risk of investment.

"It is important to understand that intrinsic value is not an exact figure, but a range that is based on your assumptions" Jean-Marie Eveillard

“Calculations of intrinsic value, though all-important, are necessarily imprecise and often seriously wrong. The more uncertain the future of a business, the more possibility there is that the calculation will be wildly off-base.” Warren Buffett

A company's intrinsic value is subject to changes in earnings expectations and changes in investor return requirements but really shouldn't fluctuate that much. The more certain the cash flows the more stable the company's intrinsic value. Intrinsic value tends to be far less volatile than a company's market value.

"Value to some extent is in the eye of the beholder. It is very hard to pin down what the value of a future set of cash flows from a business, be it a cable TV or biotechnology, is going to be. Some are easier to predict than others. But it is very hard to predict what those future cash flows are going to be. And it is very hard to ascertain the correct discount rate to bring them back to the present with." Seth Klarman

As cash flows are inherently unpredictable, its makes sense to be conservative when making estimates. The more conservative the estimates, the greater the margin of safety.

“Obviously, we can never precisely predict the timing of cash flows in and out of a business or their exact amount. We try, therefore, to keep our estimates conservative and to focus on industries where business surprises are unlikely to wreak havoc on owners.” Warren Buffett

"When we look at value, we tend to look at it on a very conservative basis - not making optimistic forecasts many years into the future, not assuming growth, not assuming favourable cost savings, not assuming anything like that. Rather looking at where it is right now, looking backward and saying, is that the kind of thing the company has been able to do repeatedly? Or is this a uniquely good year and is it unlikely to be repeated?" Seth Klarman

Market value is the value of the company at any one point in time as reflected in it's share price. The value of the whole company is the last share price multiplied by the number of shares on issue plus the company's debt, also known as enterprise value.

In reality, market value can be, and often is, significantly different from both intrinsic value and private value. Just because a stock trades at a certain price does not mean the company is worth that amount. If you have a small parcel of shares you may be able to achieve that price. If you own a large stake in the company it may not be possible to sell them all at that price.

"The underlying value of a security is distinguishable from its daily market price, which is set by the whim of buyers and sellers, as are the prices of rare art and other collectibles” Seth Klarman

Market value can be significantly above intrinsic value. Plenty of people pay more for companies than they are really worth. This may occur when they expect someone else to pay even more [ie they are speculating], they have unrealistic growth expectations, they have an investment mandate that means they have to buy, they are focused on the short term outlook, they are too optimistic, their buying decisions are quant driven [eg momentum], or they believe the share price looks cheap relative to other companies etc.

Conversely, a company's market value can be significantly below intrinsic value - the future maybe uncertain, macro factors maybe overwhelming fundamentals, investors maybe focused on the short term outlook, investors may be acting irrationally, or investors may have a mandate requiring them to sell the shares etc.

“Mr. Market gives you opportunities to buy above and below intrinsic value.” Mario Gabelli

"Growth in corporate intrinsic value is often obfuscated by stock price movement, which does not appropriately track the accretion in business value. That’s good for all of us who are appraisers of businesses, because it means you get more mispricing and better opportunity to get a franchise at a cheap price." Mason Hawkins

Market value is influenced by the same factors that affect intrinsic value but even more so by the human emotions of fear and greed. Lots of investors buy and sell shares without respect to intrinsic value. As a result, market value tends to be far more volatile than intrinsic value. It's this volatility that provides the opportunity to buy businesses below their intrinsic worth.

"Prices fluctuate more than values - so therein lies opportunity" Joel Greenblatt

"Market price is the price the stock is currently trading at. It is determined by supply and demand of sellers at a point in time and may have no relationship with private market or intrinsic value." Li Lu

"The stock market is dominated by participants that perceive stocks almost as casino chips. With that knowledge, we can then buy great businesses sometimes well below their intrinsic value" Francois Rochon

Finally, private value is the value of the company based on a price another company or private investor may pay for the whole company. Private value is influenced by the same factors as intrinsic value and is often higher than intrinsic value. This is because another company who buys the whole company has access to all of the cash flows (not just the dividends), can determine capital allocation, may get tax benefits and, or maybe able to remove duplicate costs to achieve synergy benefits to increase earnings.

It is possible for another company or private investor to pay too much above intrinsic value for the same reasons an investor pays too much - emotional factors like greed, cheap financing or a private equity buyer flush with cash, over-estimating future earnings, relying on multiples of other companies or transaction multiples etc.

"The ultimate irony is that private market value, being defined as what business people would pay was, in fact a moot point [in the mid to late 1980's]. There were no business people doing deals because the Wall Street leverage artists had prices way above what prudent business people would pay. We always attempted to define private market value as what we would pay to own a business." Seth Klarman

So how do you take advantage of the three different types of values?

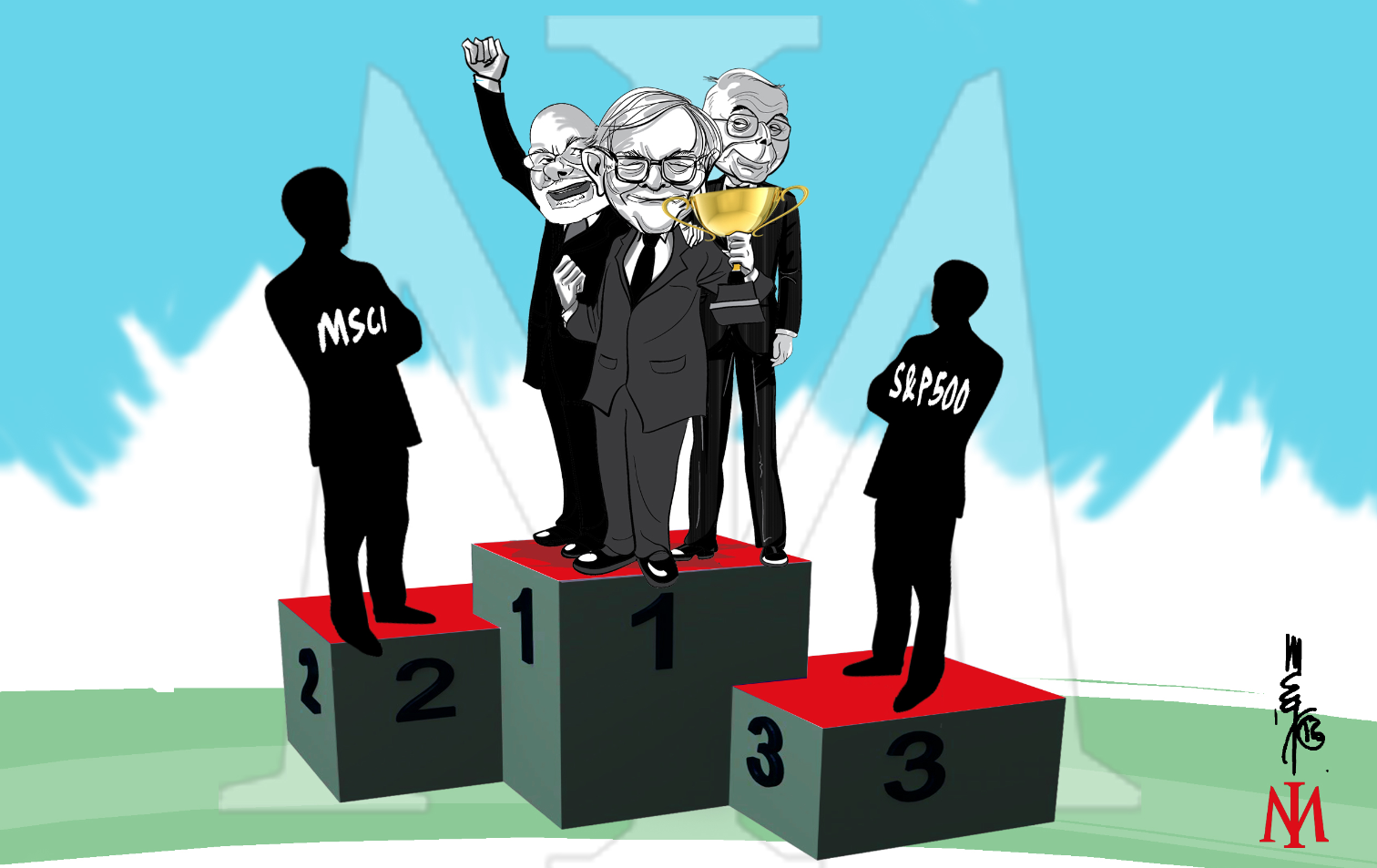

Value investors like to buy shares in companies when the market value is significantly below intrinsic and private value. Share prices, while they may move significantly from intrinsic value in the short term, have a tendency to reflect intrinsic value long term. Over time underlying business fundamentals tend to determine share prices rather than short term factors.

"The price of any particular security can be pictured as something resembling a captive balloon attached, not to the ground but to a wide line traveling through space. That line represents "intrinsic" value. As time goes on, if a company's earning power and true prospects improve, the line climbs higher and higher. If these or other basic ingredients of intrinsic value get worse, the line declines correspondingly. At any one time, the psychological influences (i.e., how the financial community is appraising these more fundamental matters of intrinsic value) will cause the price of the particular stock to be anywhere from well above this line to well below it. However, while momentary mass enthusiasm or unwarranted pessimism will cause the stock price to be far above or well below intrinsic value, it, like our captive balloon, can never get completely away from the line of true value and will always be pulled back toward that line sooner or later." Phil Fisher

The Investment Masters often refer to buying stocks well below intrinsic value as buying dollars for fifty cents or so.

“If a business is worth a dollar and I can buy it for 40 cents, something good may happen” Water Schloss

Buying shares with respect to longer term intrinsic value is a common investment strategy of many of the Investment Masters and is commonly referred to as 'time arbitrage'.

"We rely on concentrated research to identify great businesses that are trading at highly discounted valuations because investors have over-reacted to negative macro or company specific events. That's the time-arbitrage part of the strategy, taking advantage when the market reacts to short-term factors that have little impact on long-term intrinsic values" Bill Ackman

Investors who buy at a discount to intrinsic value are buying with a 'margin of safety'. If a company trades at a wide enough discount to its intrinsic value it's likely to attract other investors, other companies or private equity to take advantage of the under valuation.

"The beauty of stocks is that they do sell at silly prices from time to time. That's how Charlie and I have gotten rich." Warren Buffett

“I never want to pay above intrinsic value for stock – with very rare exceptions where someone like Warren Buffett is in charge." Charlie Munger

"The concept of a margin of safety is that an investor should purchase a security at a price sufficiently below his estimate of its intrinsic value that he will have protection against permanent loss even if his estimate proves somewhat optimistic. An analogy is an investor standing on the 10th floor of a building, waiting for an elevator to carry him to the lobby. The elevator door opens. The investor notices that the elevator is rated for 600 pounds. There already are two relatively obese men in the elevator. The investor estimates their weights at about 200 pounds each. The investor knows that he weighs 175 pounds. The investor should not enter the elevator. There is an inadequate margin of safety. Maybe he underestimated the weights of the two obese men. Maybe the elevator company overestimated the strength of the elevator’s cable. The investor waits for the next elevator. The door opens. There is one skinny old lady in the elevator. The investor says hello to the lady and enters the elevator. On his ride to the lobby, he will enjoy a large margin of safety." Ed Wachenheim

Many value investors look to the prices paid in mergers and acquisitions of similar companies to determine the potential private value of a company. When a company trades at a wide discount to that value it can provide an investment opportunity.

“Look at the prices paid in corporate mergers and acquisitions to find stocks that are selling at a significant discount to what they are actually worth to a knowledgeable buyer” Christopher Browne

The beauty of listed shares is that they are heavily influenced by human emotions. Investors are subject to tendencies and biases like groupthink, herd behaviour and basing investment decisions on recent performance. Intrinsic value and private value tend to be less influenced by human emotions.

“The big difference between private acquisitions and public equities is a negotiated transaction versus the non-negotiated transaction. When I buy stocks in the public markets, I am dealing with unintelligent sellers for the most part, or sometimes sellers that are very influenced by psychology on market nuances.” Mohnish Pabrai

This is one of the reasons many investment masters are cautious with new IPO's. The price tends to be set by rational individual[s] who look for the optimal time to maximise the sale price of the company.

“An intelligent investor in common stocks will do better in the secondary market than he will doing buying new issues. The reason has to do with the way prices are set in each instance. The secondary market, which is periodically ruled by mass folly, is constantly setting a 'clearing price'. No matter how foolish that price may be, it's what counts for the holder of a stock or bond who needs or wishes to sell, of whom there are always going to be a few at any moment. In many instances, shares worth x in business value have sold in the market for 1/2 x or less. The new issue market, on the other hand is ruled by controlling stockholders and corporations, who can usually select the timing of offerings or, if the market looks unfavourable, can avoid an offering altogether. Understandably, these sellers are not going to offer any bargains, either by way of a public offering or in a negotiated transaction. It's rare you'll find x for 1/2 x here.” Warren Buffett

Finally, many Investment Masters look for a catalyst that will close the gap between market value and intrinsic or private value. This may include things like asset sales, spin-offs, new management, buy-backs, insider buying, fixing balance sheets, closing unprofitable divisions etc. The quicker the gap can be closed the less the share price is exposed to general movements in the share market.

“One of the approaches I take is to look for a stock in the public market that is selling at a significant discount to private market value where I can identify catalysts for potential change” Leon Cooperman

"Investors should pay attention not only to whether but also to why current holdings are undervalued. Look for investments with catalysts that may assist directly in the realization of underlying value." Seth Klarman

The stock market coupled with the emotions of participants provide the opportunities for investors to buy companies below what they are worth. Provided market prices are determined by human nature that's unlikely to change.