We’ve all heard of today’s Titans; those business moguls that possess incredible net worth that rivals almost all others. Bezos, Musk, Gates, even Buffett and Munger. These are household names to both investors and businesspeople the world over. But there was one Titan that could rival them all, and indeed is regarded as the richest American to ever live. Who was it?

John D Rockefeller.

With an estimated net worth of $400b today, how did he earn that title? How did one man find himself literally crushed by money and yet was still able to retire in his mid 50’s?

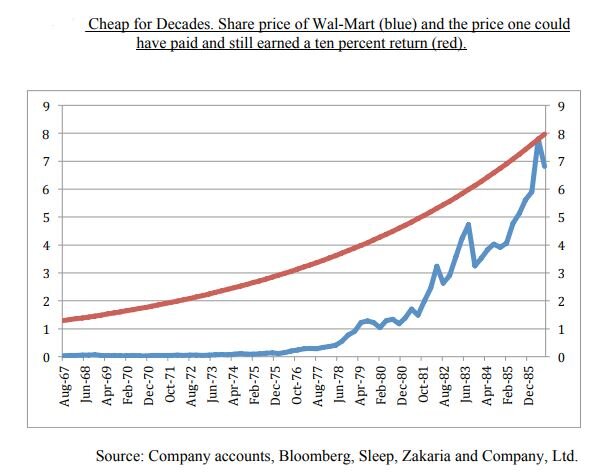

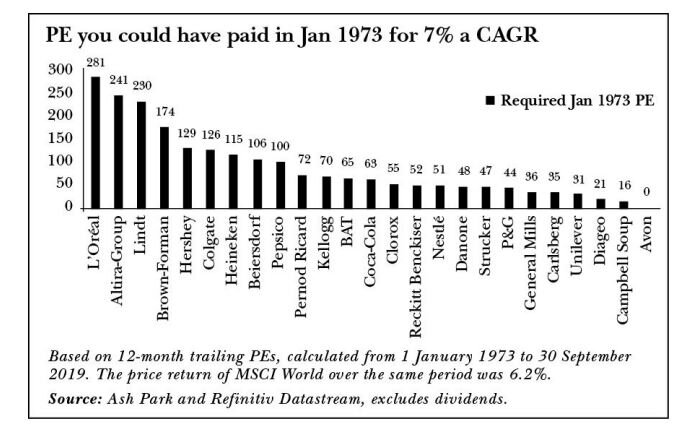

He did it by owning a great business - which is key to long term investment success. The very best businesses aren’t just slightly better than their competition, they’re orders of magnitude better. Businesses which can grow their earnings and compound their investor’s capital can underwrite their share price performance for years to come - making them one of the safest and surefire ways to investment success.

At the foundation of history’s greatest businesses is usually a powerful business model. In the case of Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, it was ‘Owning the Choke-Point,’ the narrow part of an hour glass separating suppliers and consumers; the centre of the ecosystem. It’s an enduring business model that has delivered windfall profits to company shareholders for centuries.

“Rockefeller had an annual untaxed income of $58m in 1902 - or about a billion dollars in tax-free income per annum in today’s money.”

If the names Chevron, Conoco, Exxon, Mobil or Amoco ring a bell, you’re already familiar with the legacy of Rockefeller’s business, The Standard Oil Trust. An indomitable energy company whose activities spanned production, storage, transport, infrastructure, distribution and retailing that touched consumers and businesses the world over. Standard Oil has long been considered the greatest monopoly of all time.

There are a myriad of lessons for today’s investor in the history of John D Rockefeller and Standard Oil; owning the choke-point, keeping prices low, leveraging and sharing scale, embracing technology, continuously innovating, empowering employees, decentralising, aligning management, growing the market, spurning debt, encouraging internal competition and harnessing tailwinds are as relevant today as they were over a hundred years ago.

Standard Oil’s ability to consistently increase profitability and defy the notoriously boom-bust nature of its industry descended from its ownership of the choke-point; the point where oil supply was transformed into commercial products and distributed for sale.

Rockefeller started out in refining, recognising the benefits of scale, he amalgamated capacity to extract favourable terms from the railways. As refining competitors buckled, Rockefeller drove further consolidation; taking partial stakes, retaining management, and using scrip based funding ensured interests were aligned - creating emergent effects.

Rockefeller recognised the benefits in keeping prices low; the pool of potential buyers was expanded while new competition was deterred from entering the industry. Ever frugal, Rockefeller focused on costs and looked for ways to increase efficiencies; embracing new technologies, constantly innovating and leveraging economies of scale ensured competition was muted. By 1907, the Standard Oil leviathan refined 87% of the kerosene market and was more than twenty times the size of its most serious competitor.

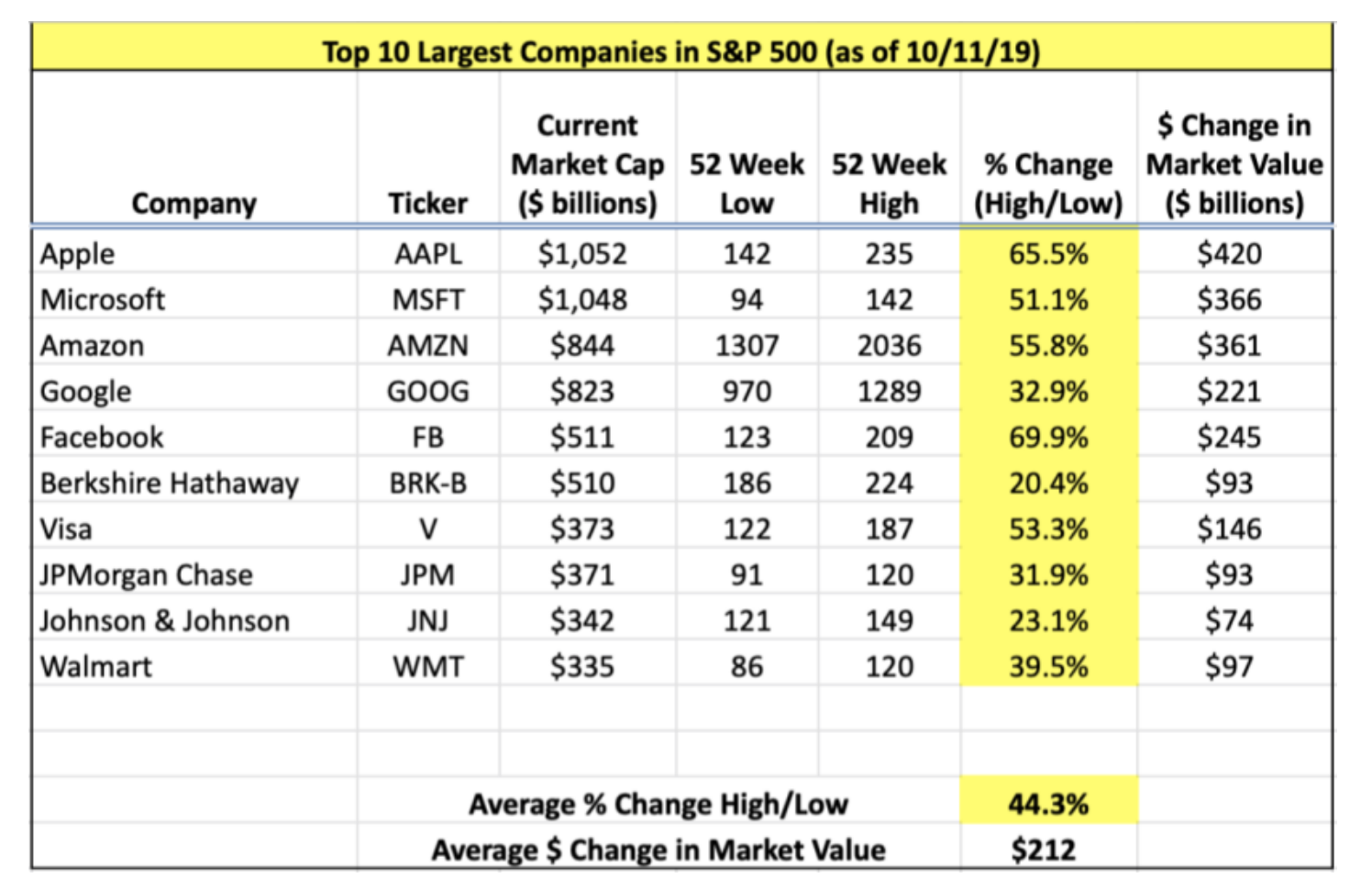

Having come of age in an era of emerging corporate dominance and nascent regulatory oversight, Standard Oil’s anti-competitive tactics [there were many!] eventually attracted Government attention. In 1911, after forty-one years of existence, the Supreme Court ordered the Trust be dismembered into thirty-seven subsidiary companies [including those five companies mentioned above]. The post split performance of Standard Oil Trust might prove a useful guidepost given the regulatory concerns overhanging some of today’s tech titans.

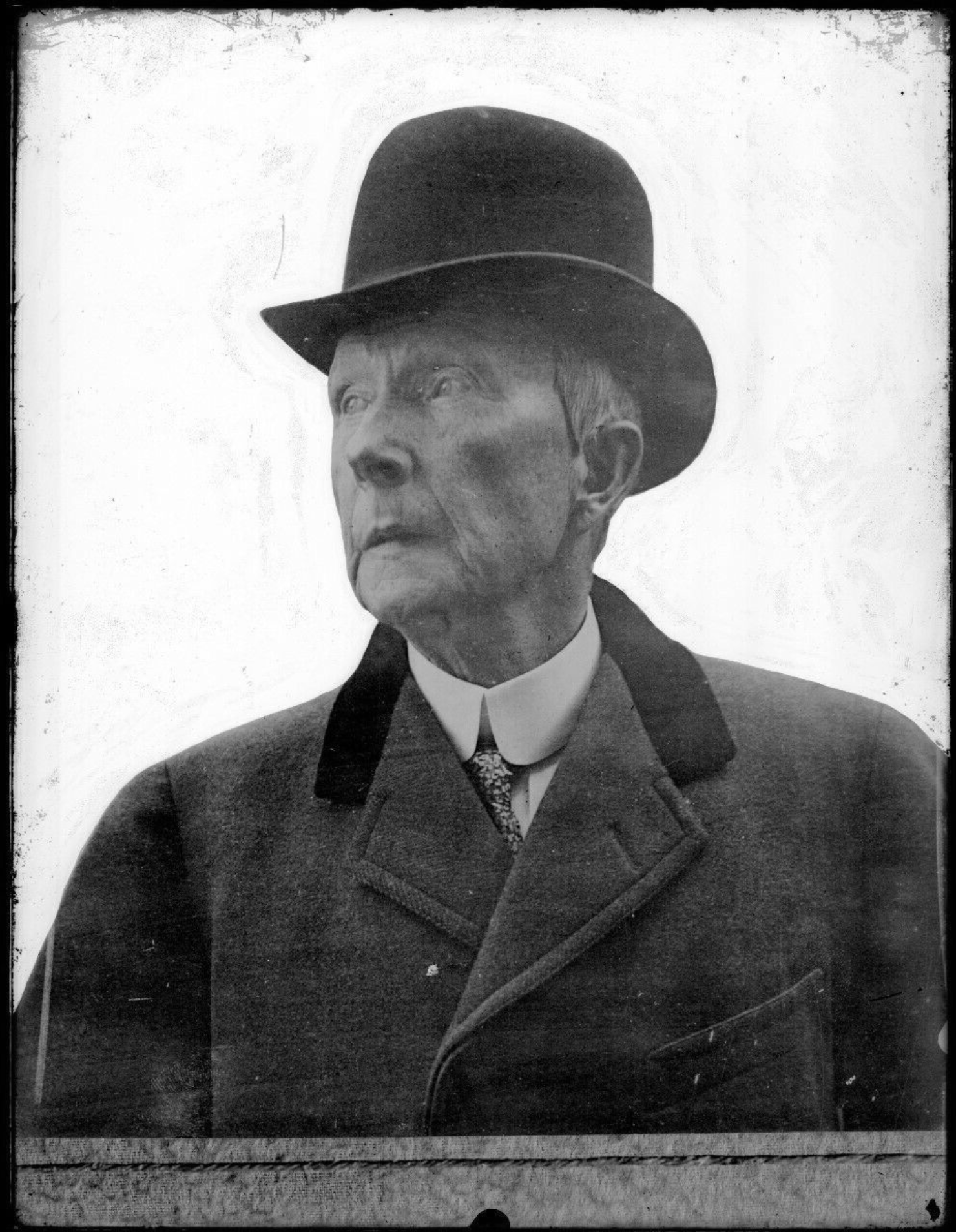

By his mid-fifties, Rockefeller had retired, yet the enormous tailwind of the automotive generation would make him far richer in retirement than in his working life. An abiding self-belief that he was fulfilling God’s wish to earn and share wealth had created a predilection for charity from an early age. At the time of Rockefeller’s death, a few weeks short of his 98th birthday, his career would be defined as much by his philanthropic endeavours as it was by his business success.

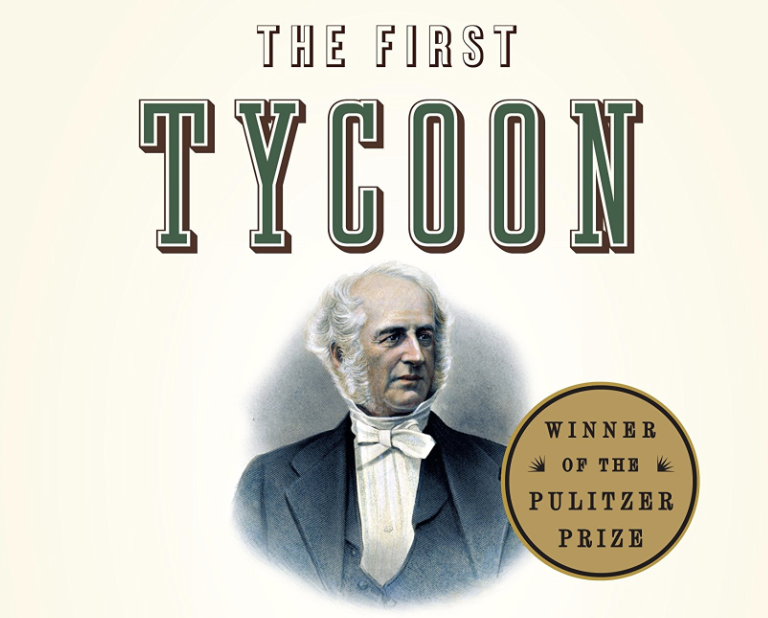

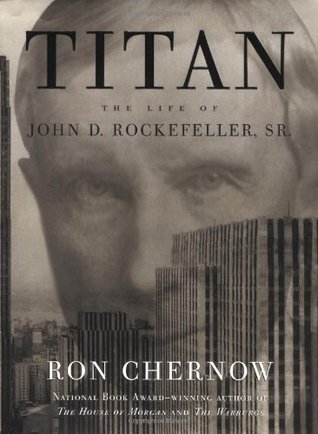

Rockefeller’s incredible story has been told in the wonderful book, ‘Titan’, by Ron Chernow.

“Another book that I liked very much was ‘Titan’, the biography of the original John D. Rockefeller. That’s one of the best business biographies I have ever read. And it’s a very interesting family story, too. That was just a wonderful, wonderful book. And I don’t know anybody who’s read it who hasn’t enjoyed it. So I would certainly recommend that latest biography of John D. Rockefeller the first.” Charlie Munger

‘Titan’ is a fantastic journey into the highly complex and contradictory mind of one of the world’s shrewdest businessmen. While not an easy read (bring a dictionary!) it’s worth the effort. While barely scratching the surface of this epic biography, I’ve included some favourite extracts below.

Education and Smarts

“‘I was not an easy student, and I had to apply myself diligently to prepare my lessons.’ said Rockefeller, who described himself accurately as ‘reliable’ but not ‘brilliant.’”

“[When playing childhood games] to ensure that he won, he submitted to games only where he could dictate the rules.”

“‘I was trained from the beginning to work and save,’ Rockefeller explained. ‘I have always regarded it as a religious duty to get all I could honourably and give all I could.’”

“Once Rockefeller spent three days helping a local farmer dig potatoes for 37 cents per day. This set up an instructive contrast for the frugal boy when, soon afterward, he loaned one farmer $50 at 7 percent interest and collected $3.50 at year’s end - without a stitch of work. He was thunderstruck by the happy math, which hit him with the force of a revelation. ‘The impression was gaining ground on me that it was a good thing to let the money be my slave and not make myself a slave to money.’”

Optimism

“[Rockefeller] was a confirmed exponent of positive thinking.”

“Like other Gilded Age moguls, Rockefeller was shaped by his faith in economic progress, the beneficial application of science to industry, and America’s destiny as an economic leader.”

“[After the 1929 market crash, Rockefeller was encouraged to make a calming statement] Rockefeller issued a press release, ‘These are days when many are discouraged. In the ninety years of my life, depressions have come and gone. Prosperity has always returned, and will again.’ In his peroration, he said, ‘Believing that the fundamental conditions of the country are sound, my son and I have been purchasing sound common stocks for some days.’”

Embrace Technology

“The firm relied upon the railroad and the telegraph, the two technologies then revolutionising the American economy.”

“Standard Oil also profited immeasurably from the revolution in oil transport as barrels gave way to tank cars.”

“The railroads balked at investing in rolling stock that couldn’t also transport general freight, So Rockefeller stepped boldly into the breach… As the owner of almost all the Erie and NY Central tank cars, Standard Oil’s position grew unassailable.”

“Only belatedly did Rockefeller discern the full potential of pipelines… [Ultimately] gaining uncontested control of all major pipeline systems connecting oil wells to railroad trunk lines. ‘Practically not a barrel of oil could get to a railroad without Rockefeller’s consent… ‘Rockefeller’s firm had now advanced far beyond the railroads to more efficient pipelines.’”

Understand the Business

“For Rockefeller, ledgers were sacred books that guided decisions and saved one from fallible emotion. They gauged performance, exposed fraud, and ferreted out hidden inefficiencies. In an imprecise world, they rooted things in solid empirical reality. As he chided slipshod rivals, ‘Many of the brightest kept their books in such a way that they did not actually know when they were making money on a certain operation and when they were losing.’”

Efficiency and Scale Advantages

“The proliferation of railroads enabled Rockefeller to extract discounts from them by playing one off against the other.”

“Rockefeller’s ceaseless search for even minor improvements meant that within a year refining had overtaken produce as the most profitable side of the business. Despite the unceasing vicissitudes of the oil industry, prone to cataclysmic booms and busts, he would never experience a single year of loss.”

“His tight-fisted control of details and advocacy of unbridled expansion. Daring in design, cautious in execution - it was a formula he made his own throughout his career.”

“[Rockefeller] was a mastermind of many negotiations with the railroads.. Since oil was a relatively cheap, standardised commodity, transportation costs inevitably figured as a critical factor in the competitive struggle.”

“Rockefeller had built gigantic plants so he could drastically slash his unit costs. Even his first partner remembered that ‘the volume of trade was what he always regarded as of paramount importance.’ Early on, Rockefeller realised in the capital-intensive refining business, sheer size mattered greatly because it translated into economies of scale.”

“Once describing the ‘foundation principle’ of Standard Oil, Rockefeller said it was the ‘theory of the originators’ .. that the larger volume the better the opportunities for the economies, and consequently the better opportunities for giving the public a cheaper product without .. the dreadful competition of the late ‘60’s ruining the business. During his career, Rockefeller cut the unit costs of refined oil almost in half, and he never deviated from this gospel of industrial efficiency.”

Emerging Effects

“Rockefeller activated a self-sustaining movement as his new allies agreed to consolidate business in their localities and supervise the purchase of remaining independent refiners. A massive chain reaction was thus set in motion that rippled through both refining centres, with local businessmen acting as Rockefeller’s agents.”

Owning the Choke-Point

“The spot chosen for the new refinery tells much in miniature about Rockefeller’s approach to business… Able to ship by water or land, Rockefeller gained the critical leverage he needed to secure preferential rates on transportation - which was why he agonised over plant locations throughout his career.”

“[Rockefeller’s] overriding reason for his attachment to Cleveland: It was the hub of so many transportation networks that he had tremendous room to manoeuvre in freight negotiations.”

“Rockefeller’s first visit to Pennsylvania must have persuaded him that he had picked the right entry point to the business. Searching for oil was wildly unpredictable, whereas refining seemed safe and methodical by comparison. Before too long, he realised that refining was the critical point where he could exert maximum leverage over the industry.”

“Rampant speculation had so overbuilt the industry that total refining capacity in 1870 was triple the amount of crude oil being pumped. By then, Rockefeller estimated 90 percent of all refiners were operating in the red. Producers and refiners didn’t shut down operations in the expected numbers causing Rockefeller to doubt the workings of Adam Smith’s invisible hands: ‘So many wells were flowing that the price of oil kept falling, yet they went right on drilling.’ The industry was trapped in a full blown crisis of overproduction with no relief.’ Thus in 1869, Rockefeller feared his wealth might be snatched away from him. As someone who tended toward optimism, ‘seeing opportunity in every disaster’, he studied the situation exhaustively instead of bemoaning his luck. He saw that his individual success as a refiner was now menaced by industrywide failure and that it therefore demanded a systematic solution. This was a momentous insight, pregnant with consequence. Instead of just tending to his own business, he began to conceive of the industry as gigantic, interrelated mechanism and thought in terms of strategic alliances and long term planning. Rockefeller cited the years 1869 and 1870 as the start of his campaign to replace competition with cooperation in the industry. The culprit, he decided, was ‘the over-development of the refining industry,’ which had created ‘ruinous competition.’ If this fractious industry was to be made profitable and enduring, he would have to tame and discipline it. A trailblazer who improvised solutions without any guidance from economic texts, he began to envision a giant cartel that would reduce overcapacity, stabilise prices, and rationalise the industry.”

“Between February 17 and March 28 1972 - between the first rumours of the SIC [proposed agreement between Standard Oil and the railways] and the time it was scuttled - Rockefeller swallowed up twenty-two of his twenty-six Cleveland competitors… Another businessman might have started with small, vulnerable firms, building on easy victories, but Rockefeller started at the top, believing that if he could crack his strongest competitor first, it would have tremendous psychological impact.”

“In retrospect, it seems peculiar that Standard Oil - omnipotent in refining, transportation, and distribution - owned just four production properties in the early 1880’s… He had long profited from the juxtaposition of cooperation in refining and competition in production.”

“Rockefeller applied to iron ore [interests] lessons he had learned in oil, such as controlling an industry through transportation and demoralising competitors with prices too low for them to match.”

“The unity of Standard Oil partners was especially impressive given the organisation’s byzantine structure, a far-flung patchwork of firms, each nominally independent but in reality taking orders from 26 Broadway [Standard Oil head office].”

Innovation

“Scarcely dreaming that oil would ever supersede their main [agricultural produce] commodity business, they [Rockefeller & partner] considered it ‘a little side issue.’”

“Rockefeller wasn’t stultified by precedent or tradition, which made it easier for him to innovate. He continued to value autonomy from outside suppliers. At first, he paid small coopers up to $2.50 for white oak barrels before he showed, in an early demonstration of scale, that he could manufacture dry, tight casks.. for less than a dollar a barrel. The Cleveland coopers bought and shipped green timber to their shops, whereas Rockefeller had the oak sawed in the woods and dried in kilns, reducing its weight and slicing transportation costs in half.”

“Regarding each plant as infinitely perfectible, Rockefeller created an atmosphere of ceaseless improvements.”

“Below the executive committee came a battery of specialised committees dedicated to transportation, pipelines, domestic trade, export trade, manufacturing, purchasing and so on. These committees standardised the quality of subsidiaries engaged in similar work, enabling managers to swap insights and align their operations… These were chosen experts who had daily sessions and study of the problems, new as well as old, constantly arising. The benefit of their research, their study, was available for each of the different concerns.”

“Rockefeller created the model for the vertically integrated oil giants that would straddle the globe in the twentieth century.. By 1891 Rockefeller had gained control of a quarter of American oil production.”

Tailwinds

“The [civil] war had stimulated growth in the use of kerosene by cutting the supply of southern turpentine .. kerosene emerged as an economic staple and was primed for a furious postwar boom.”

“The [civil] war markedly accelerated the timetable of economic development, promoting the growth of factories, mills, and railroads. By stimulating technological innovation and standardised products, it ushered in a more regimented economy. The world of small farmers and businessmen began to fade, upstaged by a gargantuan new world of mass consumption and production.”

“Europe emerged rapidly as the foremost market for American kerosene, importing hundreds of thousands of barrels yearly during the civil war. Perhaps no other American industry had such an export outlook from its inception. By 1866, fully two-thirds of Cleveland kerosene was flowing overseas.”

Low Prices

“Rockefeller’s goal was to forestall potential competitors through low prices and thus minimise risk and chance disruptions.”

“Standard Oil had not kept prices low out of altruism but to deter competition and ‘keep our profits on such a basis that others would not be stimulated to enter the field of competition with us.’ This belied Rockefeller’s frequent claim that his motive was to bequeath cheap oil to the working people.”

“Rockefeller was obsessed with high-volume, low cost production to maintain market share, even if he temporarily sacrificed profit margins. As he noted, ‘This fact the Standard Oil Company always kept in mind: that they must render the best service and be content with largely increasing volume of business, rather than increase the profit so as to tempt others to compete with them.’ When discussing prices with subordinates, he frequently reminded them, ‘We want to continue, in reason, that policy which will give us the largest percentage of business.’”

“In general, Standard Oil did an excellent job at providing kerosene at affordable prices. It boasted far lower unit costs than competitors and relentlessly drove down costs over the years.’ Between 1880 and 1885, its average cost of processing a gallon of crude oil went from 2.5 to 1.5 cents. [In the 20 years to 1890] the retail prices of kerosene had plunged from 23.5 cents to 7.5 cents per gallon.”

“But Standard Oil never sought a perfect monopoly because Rockefeller realised that it was politically prudent to allow some feeble competition.. A very smart monopolist, Rockefeller kept prices low enough to retain control of the market but not so low as to wipe out all lingering competition.”

“Rockefeller new that if he got greedy, other products could be substituted for kerosene, and this, too, curbed his appetite for excess profits.”

“Rockefeller keenly felt a need to freeze the industry’s size, stymie new entrants, and create an island of stability in which expansion and innovation could then occur unimpeded.”

John D Rockefeller’s NY Residence

Empowering People

“Rockefeller wanted to be surrounded by trustworthy people who could inspire confidence in customers and bankers alike.”

“In the early days, Rockefeller knew the name and face of each employee.”

“Rockefeller generally received excellent reviews from employees who regarded him as fair and benevolent, free of petty temper and dictatorial airs.”

“So highly did Rockefeller value personnel that during the first years of Standard Oil he personally attended to routine hiring matters.”

“‘The ability to deal with people is as purchasable a commodity as sugar or coffee,’ Rockefeller once said, ‘and I pay more for that ability than for any other under the sun.”

“Employees were invited to send complaints or suggestions directly to Rockefeller, and he always took an interest in their affairs. His correspondence is replete about sick or retired employees. Reasonably generous in wages, salaries, and pensions, he paid somewhat above the industry average.”

“His employees tended to revere Rockefeller and vied to please him. As one said, ‘I have never heard of his equal in getting together a lot of the very best men in one team and inspiring each man to do his best for the enterprise.”

“At first, Rockefeller tested employees exhaustively, yet once he trusted them, he bestowed enormous power upon them and didn’t intrude unless something radically misfired.”

“People who worked for Rockefeller usually found him a model of propriety and paternalistic concern.”

“Rockefeller’s decided the leading men [management co-owners] would receive no salary but would profit solely from the appreciation of their shares and rising dividends - which Rockefeller thought a more potent stimulus to work.”

“When it came to mergers, Rockefeller didn’t fight for the last dollar and tried to conclude matters cordially. Since he aimed to convert competitors into members of his cartel and often retained the original owners.”

“The creation of Standard Oil was often less a matter of stamping out competitors than of seducing them into co-operation. In general, Rockefeller was so eager to retain original management that he accumulated expensive deadwood on the payroll and, for the sake of intra-empire harmony, preferred to be conciliatory.”

“One of Rockefeller’s greatest talents was to manage and motivate his diverse associates. As he said, ‘It is chiefly to my confidence in men and my ability to inspire their confidence in me that I owe my success in life.”

“Free of an autocratic temperament, Rockefeller was quick to delegate authority and presided lightly, genially, over his empire, exerting his will in unseen ways.”

“The Trust’s formation created negotiable securities, and this profoundly affected the Standard Oil culture. Not only did Rockefeller urge underlings to take stock but made money abundantly available to do so. As such shareholding became widespread, it welded the organisation more tightly together, creating an esprit de corps that helped in steamrolling competitors and government investigators alike. With employees receiving huge capital gains and dividends, they converted Standard Oil into a holy crusade.”

“Rockefeller hoped the Trust would serve as a model for a new populist capitalism, marked by employee share ownership. ‘I would have every man a capitalist, every man, women and child,’ he said, ‘I would have everyone save his earnings, not squander it; own the industries, own the railroads, own the telegraph lines.”

“[Rockefeller’s] committee system was an ingenious adaption, integrating the policy of constituent companies without stripping them of all autonomy. We must remember that Standard Oil remained a co-federation and most of its subsidiaries were only partially owned. A top down hierarchical structure might have hampered local owners whom Rockefeller had promised a measure of autonomy in running their plants. The committee system galvanised their energies while providing them with general guidance. The committee encouraged rivalry among local units by circulating performance figures and encouraging them to compete for records and prizes. The point is vitally important, for monopolies spared the rod of competition, can easily lapse into sluggish giants.”

Walk The Floors

“In the first years of Standard Oil, Rockefeller regularly toured his facilities and was extremely inquisitive and observant, soaking up information and assiduously quizzing plant superintendents. In his pocket, he carried a little red notebook in which he jotted suggestions for improvements and always followed up on them.”

Financial Strength

“[Rockefeller] always moved into battle backed by abundant cash. Whether riding out downturns or coasting on booms, he kept plentiful reserves and won many bidding contests simply because his war chest was deeper.”

“Standard Oil weathered the six-year depression magnificently, a fact Rockefeller attributed to its conservative financial policy and unparalleled access to bank credit and investor cash.”

“The Standard Oil Trust’s resilience during the depression of the 1890’s, its tested immunity from market fluctuations, cheered Rockefeller, who attributed this to Standard’s large cash reserves and conservative dividend policy.”

“Since the early 1880’s, Standard Oil had been self-financing, very liquid at all times, and free from the thrall of Wall Street bankers.”

Grow the Market

“To inflate demand, Rockefeller sold hundred of thousands of cheap lamps and wicks and sometimes distributed them gratis with the first kerosene purchase.”

“Rockefeller also sold, almost at cost, heaters, stoves, lamps, and lanterns to widen the market. In the manner of a modern corporation, Standard Oil created demand as well as satisfied it.”

“Rockefeller continually extended the market for petroleum by-products, selling benzine and paraffin, and petroleum jelly in addition to kerosene.”

Fanaticism & Obliquity

“Rockefeller derived a glandular pleasure from work and never found it cheerless drudgery. In fact, the business world entranced him as a fount of inexhaustible wonders. ‘It is by no means from money alone that these active-minded men labor - they are engaged in a fascinating occupation.’ he wrote in his memoirs. ‘The zest of the work is maintained by something better than mere accumulation of money.”

“Rockefeller seemed destined to succeed as much from his fastidious work habits as from innate intelligence.”

“Even in as a young man, Rockefeller was extremely composed in crisis. In this respect, he was a natural leader; The more agitated others became, the calmer he grew.”

“The passion for excellence originated with Rockefeller and radiated throughout the organisation. The ethos of Standard Oil’s operations around the world was John D Rockefeller’s personality writ large.”

“Rockefeller inspired subordinates with his fanatic perfectionism.”

Humility

“Aside from the occasional courtesy call from other moguls, he hobnobbed with the same family members, old friends, and Baptist clergy who had always formed his social circle.”

“When someone expressed surprise to Rockefeller that he had not gotten a big head, he replied, ‘Only fools get swelled up over money.’ Comfortable with himself, he needed no outward validation of what he had accomplished.”

“Rockefeller preferred outspoken colleagues to weak-kneed sycophants and welcomed differences of opinion so long as they weren’t personalised.”

Frugality

“From his mother he learned economy, order, thrift, and other bourgeois virtues that figured so largely in his success at Standard Oil.’”

“Rockefeller engaged in strenuous rituals of austerity, and grimly sought to simplify his life and reduce his wants. He liked to say that ‘a man’s wealth must be determined by the relation of his desires and expenditures to his income. If he feels rich on ten dollars, and has everything else he desires, he really is rich.’”

“Rockefeller spent a ridiculous amount of time protesting bills both large and small.”

“[Rockefeller would say,] save when you can and not when you have to.”

“The world’s richest man never lost the thrifty boyhood habits that had made him the nonpareil of American business.”

Secrets

“Rockefeller trained himself to reveal as little as possible.”

“He learnt to cultivate a secretive style and a defiant attitude toward strangers.”

“Rockefeller never allowed his office decor to flaunt the prosperity of his business, lest it arouse unwanted curiosity.”

“Rockefeller was concerned that if he advertised his own wealth through fancy houses, he might attract investors into the refining business and only worsen the excess capacity problem.”

“Ever alert against industrial espionage, Rockefeller never wanted people to know more than was required and warned one colleague, “I would be very careful about putting someone into a position where he could learn about our business, and be troublesome to us.”

“Rockefeller equated silence with strength. Weak men had loose tongues and blabbed to reporters, while prudent businessmen kept their own counsel.”

Anti-Competitive Tactics

“Since the rules of the game had not yet been encoded into law, Rockefeller and his fellow industrialists had forged them in the heat of combat. With his customary thoroughness, Rockefeller had devised an encyclopaedic stock of anti-competitive weapons. Since he had figured out every conceivable way to restrain trade, rig markets, and suppress competition, all reform-minded legislators had to do was study his career to draw up a comprehensive antitrust agenda.”

“Rockefeller perfected a monopoly that indisputably demonstrated the efficiency of large scale-business.”

Post Split

“During the ten years after Standard Oil’s 1911 dismantling, the assets of its constituent companies quintupled in value.”

“Those who had seen the Standard Oil dissolution as a condign punishment for Rockefeller were in for a sad surprise: It proved to be the luckiest stroke of his career. Precisely because he lost the antitrust suit, Rockefeller was converted from a mere millionaire, with an estimated net worth of $300 million in 1911, into something just short of history’s first billionaire.”

“What quickly grew apparent, however, was that Rockefeller had been extremely conservative in capitalising Standard Oil and that the split-off companies were chock full of hidden assets. Two other factors encouraged a veritable feeding frenzy in the stocks. For years, the shares of Standard Oil of New Jersey had been depressed by the antitrust litigation, but with the litigation ended, they bounced back to more normal levels. And the explosion of the automobile industry created euphoria about the endless growth prospects of the petroleum industry.”

“Many of the newly independent companies were powerful enough to inspire fear as freestanding entities. Standard Oil of New Jersey remained the world’s largest oil company, second only to US Steel in size among American enterprises and retaining 43% of the value of the old trust.”

Philanthropy

“During his first year on the job, the young [Rockefeller] donated about 6 percent of his wages to charity, some weeks much more. ‘I have my earliest ledger and when I was only making a dollar a day I was giving five, ten, or twenty-five cents.”

“Even as a teenager, he took palpable pleasure in distributing money for charitable purposes, and he insisted that from an early date he discerned the intimate spiritual link between earning and dispensing money.”

“Since his adolescence, charity had been interwoven with the fabric of his life.”

“Rockefeller argued that the rich should donate large sums to worthy causes during their lifetimes, less their money be frittered away by idle heirs.”

“Rockefeller regarded his fortune as a public trust, not as a private indulgence, and pressure to dispose of it grew imperative in the 1900’s as his Standard Oil stock and other investments appreciated fantastically.”

“Rockefeller believed that certain universal principles of businesslike efficiency should apply to non-profit ventures no less than to profit-making ones.”

“Never before had a rich benefactor spent his money in this area.. ‘It marked the first large public recognition of medical education and research as a rewarding subject of philanthropy.’”

“Rockefeller Foundation played an integral part in the rise of American medicine to the pinnacle of world leadership.”

“Rockefeller’s philanthropy was more orientated toward the creation of knowledge, and if it seemed more impersonal, it was also far more pervasive in its effect.”

“The fiercest robber baron had turned out to be the foremost philanthropist.”

“Rockefeller established the promotion of knowledge, especially scientific knowledge, as a task no less important than giving alms to the poor or building schools, hospitals, and museums.”

Summary

Studying history’s great businesses and managers can enlighten us to factors that characterise success and help shed light on new investment opportunities. While technologies change and economies evolve, the business models that define these great companies can endure for decades, even centuries.

Since the days of Standard Oil, many businesses have achieved effective ownership of the choke-point. Even the Mafia recognised the significant benefits accruing to such a position when they controlled New York’s concrete industry in the 1980’s. Collecting a tax of 1-2 percent on every new skyscraper - if you wanted to build you had to talk to the Mob.

More recently we’ve witnessed a multitude of companies monopolising industry choke-points. The capital-light nature of some of these technology businesses with their first mover advantages, network effects, increasing returns and winner-take-all dynamics may mean even longer life cycles.

Businesses which can compound capital for decades are the holy grail of investing. Charlie Munger likes to remind us, "There are certain fundamental models out there that do not take the kind of ability that quantum mechanics requires. You just have to know a few simple things and really know them.” The choke-point is one of them.

“There was only one John D Rockefeller,” concludes Chernow’s epic biography. Indeed, there was.

Reference:

‘Titan - The Life of John D Rockefeller, Sr,’ Ron Chernow, 1998, Random House.

Follow us on Twitter : @mastersinvest

* NEW * Visit the Blog Archive

TERMS OF USE: DISCLAIMER

![S Truett Cathy [Source: Chick-fil-A]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/568cf1da4bf1182258ed49cc/1625470889696-3YKLQ7FZUYR7FHDT7U7X/truett-web.jpg)

![S&P500 [grey] vs General Electric [blue] Normalised - 2000 - 2021 [Source: Bloomberg]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/568cf1da4bf1182258ed49cc/1626240958557-MQY5UOVVQ98IF9CHHKM1/Screen+Shot+2021-07-14+at+3.33.36+pm.png)

![Estée Lauder vs SP500 1995-2021 [Source: Bloomberg]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/568cf1da4bf1182258ed49cc/1622953763962-A339S3D8A10QJA6BVXPE/Screen+Shot+2021-06-06+at+2.28.10+pm.png)

![Dow Jones Industrial Average - 1987 Crash [Source; Bloomberg].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/568cf1da4bf1182258ed49cc/1616478903417-5MBL252INY28HCUPDPYG/dow.PNG)

![Disney Corporation vs S&P500 - March 2005 to 2021 [Source: Bloomberg]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/568cf1da4bf1182258ed49cc/1613102921408-U4VQK7OGPQ515OR2Y2LI/dischart.JPG)