MastersInvest has spent a lot of time studying businesses and business leaders that have been successful, some remarkably so. Those companies that have forged not only stellar reputations in their fields, but also those who have succeeded in industries where success is not a common commodity. And whilst a solid working knowledge of these success stories is vital for any investor to know, its also incredibly valuable to look at the other side of the coin - those businesses that have failed.

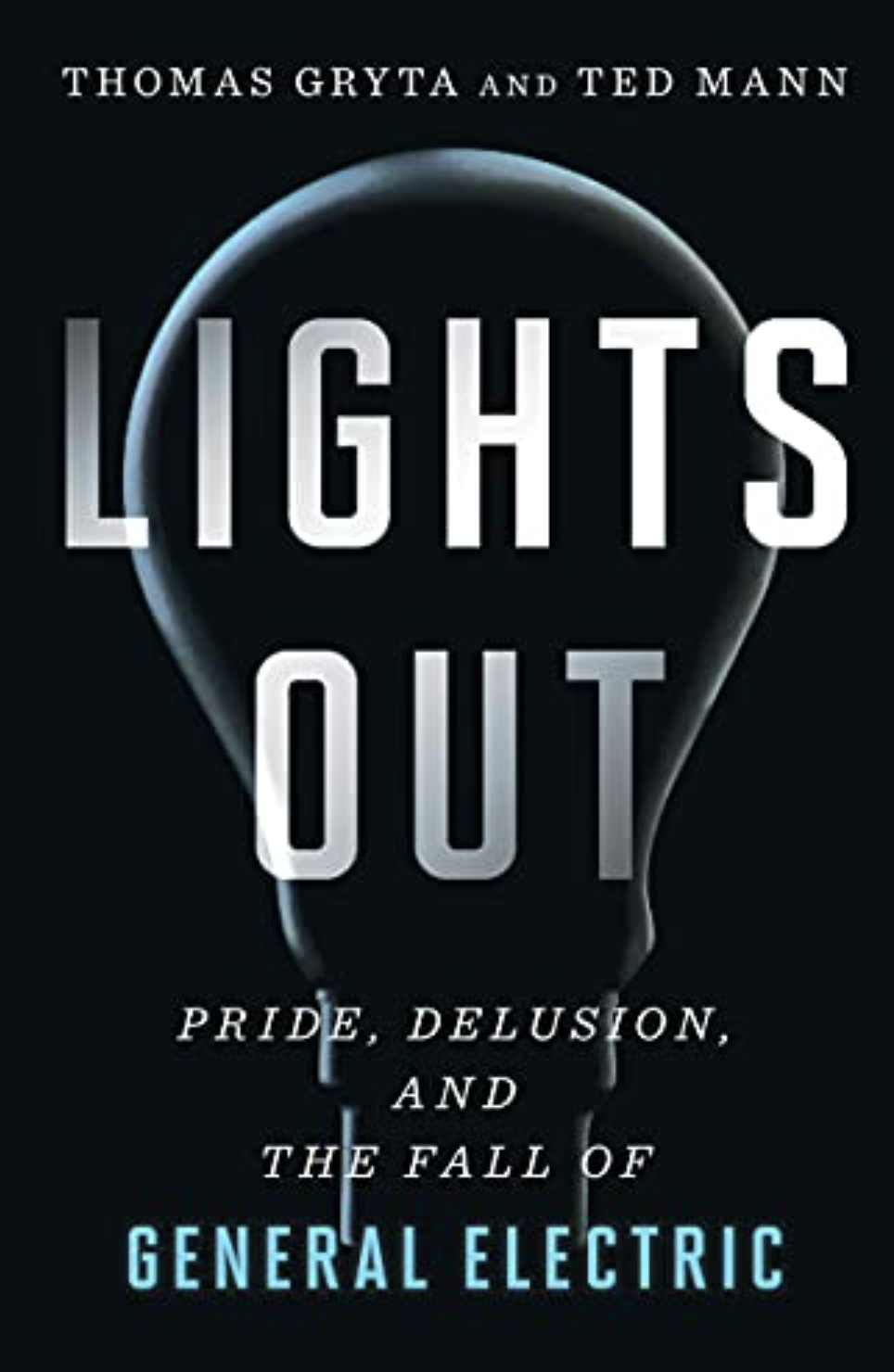

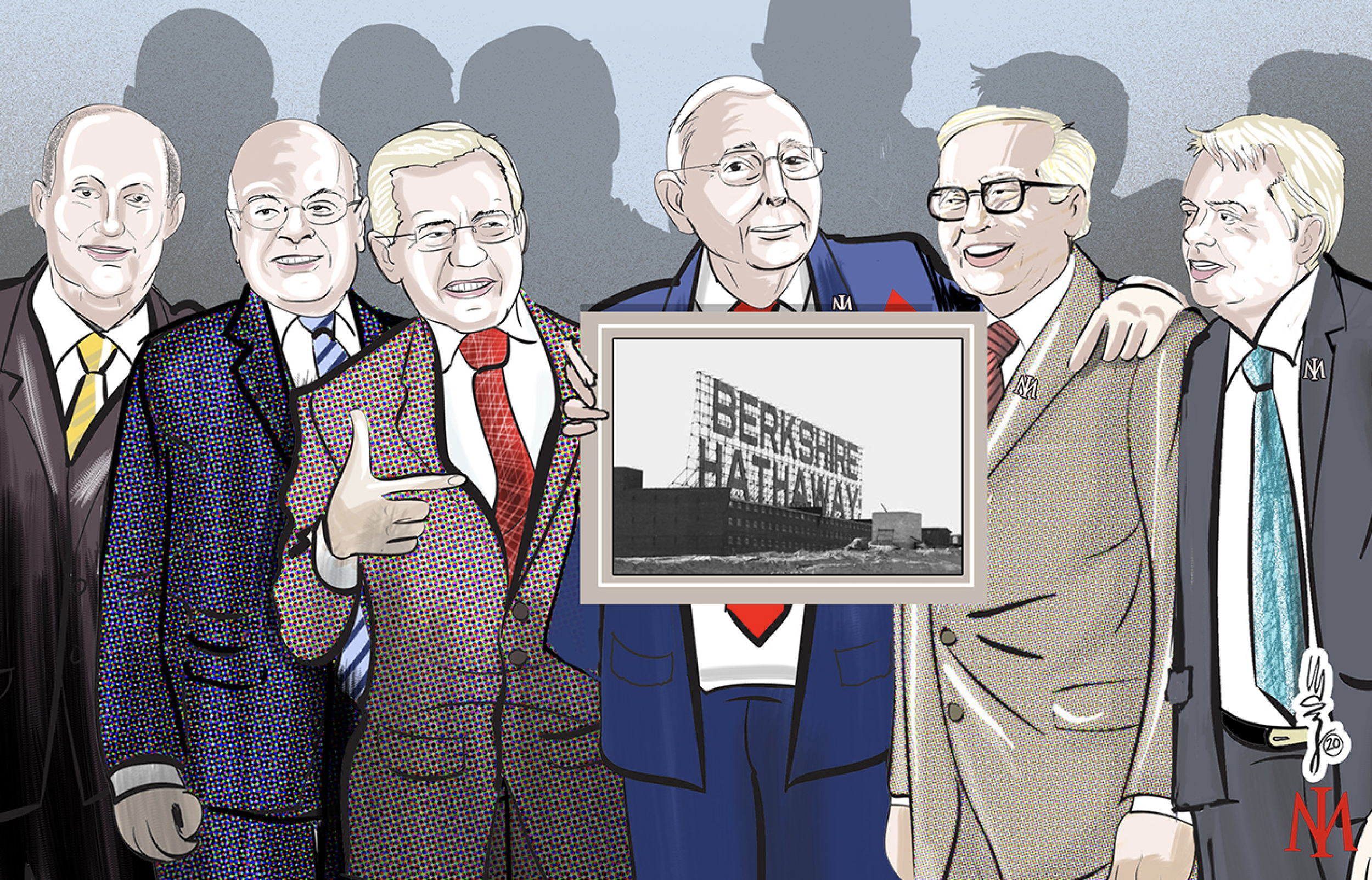

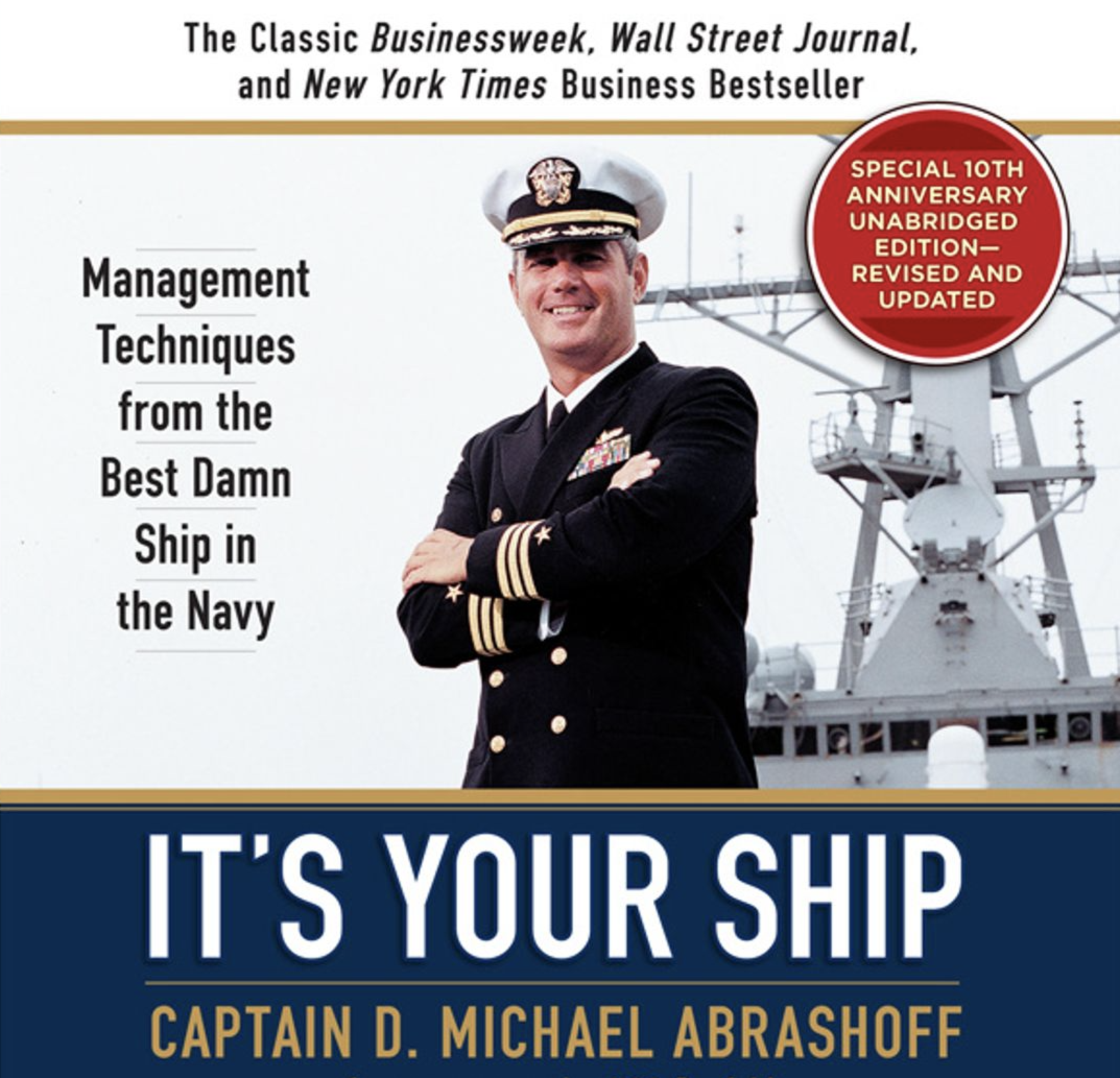

Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger have long espoused the benefits of studying failure. Armed with the foresight of what not to do can help an investor avoid the key risk to any investment program - the permanent loss of capital. With this insight in mind, and having read a short synopsis in Bill Gates Summer Reading List, I looked forward to reading the book, ‘Lights Out - Pride, Delusion and the Fall of General Electric’ by Ted Mann and Thomas Gryta. An easy read, the book details the multitude of problems which beset GE coupled with a cornucopia of red flags to look out for in your own investments.

“I like to study failure… we want to see what has caused businesses to go bad." Warren Buffett

Once a storied industrial leader, the last few decades have been nothing short of brutal for GE. While a toxic culture of ‘making the numbers’ seemed ingrained at the time Jack Welch handed the reigns to Jeff Immelt, Immelt’s sixteen year term atop GE earned him a scathing review. Characterised with an incessant focus on the share price, always coveting Wall Street’s admiration, ignorant of tail risks, obstructive to feedback, turning a blind eye to questionable accounting and an absence of humility were the hallmarks of a failed leadership tenure. If the expression, ‘an institution is the lengthened shadow of one man’ rings true, this isn’t a book for Immelt’s trophy cabinet.

Gates Notes - ‘5 Ideas for Summer Reading’ 2021

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the company’s travails were strikingly at odds with the traits that have defined the great businesses we’ve reviewed in the past. Below I’ve called out some red flags and accompanying lessons from GE. Notwithstanding the accounting misconduct, most of the tell-tale signs of trouble are qualitative and behavioural in nature.

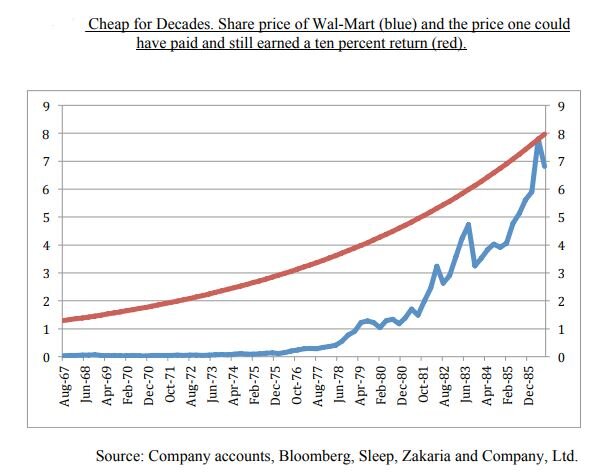

S&P500 [grey] vs General Electric [blue] Normalised - 2000 - 2021 [Source: Bloomberg]

Financials Above Purpose

In the superb book, ‘In Search of Excellence,’ Tom Peters noted, “We found that companies whose only articulated goals were financial did not do nearly as well financially as companies that had broader sets of values.”

“The Growth Playbook [was] a grueling annual examination of GE’s eight major business leaders. It was here that GE hammered out targets for sales and profits, setting the underlying assumptions for the financial estimates it would give investors. Under Immelt, the point of the exercise was determining how his executives would get to their financial targets - though not how they would determine what output the business would produce as a starting point. This practice had been ingrained at GE from the days of Welch.” Lights Out

“The problems stemmed not from any single action but from the practices of accountants on staff at the dozen or so plants in the division. They’d reported their numbers by working backward: starting with a profit target and then working out what their sales figures would have to show to get there, rather than simply running the business and reporting their results to headquarters every three months.” Lights Out

The best business leaders have long recognised a company’s share price is a function of long term business performance. Solve for the latter, and in time, the share price will look after itself. At GE the financials dictated strategy.

“Investors and executives need to realise that the creation of shareholder value is an outcome — not an objective.” Terry Smith

“Stock price is an outcome. You can’t manage the outcome. You manage the inputs.” James Gorman

“We want corporate management to solve for value creation, not security price.” Dan Loeb

“Companies that focus on their stock price will eventually lose their customers. Companies that focus on their customers will eventually boost their stock price. This is simple, but forgotten by countless managers.” Morgan Housel

“When it comes to discussing a company’s strategy, it is alarming how frequently one finds confusion about what a strategy actually is. Often a CEO mistakes a short-term target, say an earnings per share target or a return on capital threshold, with a strategy.” Marathon Asset Management

“Some would claim that maximising profits is a business’s ultimate purpose. Yet it is often when companies become exclusively profit orientated – and explicitly define this as their objective - that things go wrong. The end result of what investors seek, good shareholder returns, is invariably better achieved obliquely.” Nick Train

“An annual report with a numbers obsession speaks volumes about what’s important.” Marianne Jennings

Jeff Immelt’s strategy was directed with reference to the share price; providing guidance, smoothing earnings, setting optimistic long term EPS targets, undertaking acquisitions and divestments to appease Wall Street, appealing to big investors and ‘making the numbers’ regardless of cost. All are misguided short cuts.

Focus on Share Price

Of all the books on great businesses I’ve read, I can’t recall one where a company’s share price featured so prominently. Great businesses are all about empowering people, innovating, delighting customers, tolerating mistakes, focusing on the long term, upholding values, embracing change and remaining humble, to name but a few - none of which rated barely a mention.

“The stock market didn’t appreciate what GE was really worth. And it was driving Jeff Immelt crazy. His handlers claimed that he didn’t watch the daily movement in the shares, but his actions betrayed him. The stock market was the ultimate scoreboard tracking his performance.” Lights Out

“‘The stock is currently trading at one of the lowest earnings multiples in a decade,’ Immelt wrote in his annual letter to investors in early 2006. ‘Investors decide the stock price, but we love the way GE is positioned. We know it is time to go big!’ he wrote.” Lights Out

“Always aware of the stock’s reflection on his leadership, Immelt was trapped in a waking nightmare.” Lights Out

“GE’s stock price and its miserable performance were a constant cloud over Immelt’s head.” Lights Out

A management’s obsession with their share price is often a tell for investors; as recognised by some of the world’s best.

“Today, it seems to be regarded as the duty of CEOs to make the stock go up. This leads to all sorts of foolish behaviour.” Charlie Munger

“[The managers we have owned] don’t have a screen in their office showing them the price of their stock. And lots of them do. Sometimes you find it in the lobby of a company and sometimes you find it on the CEO’s desk. That doesn’t interest us. Their focus is on the wrong thing, in our judgement.” Chuck Akre

“We’ve been suspicious of companies that place a whole lot of emphasis on the price of their stock. When we see the price of a stock posted in the lobby of the headquarters or something, things like that make us nervous.” Warren Buffett

“A worrying sign is a CEO with a subscription to Bloomberg as this may indicate an unhealthy interest in stock prices and short-term news flow to the detriment of long-term thinking.” Marathon Asset Management

Quarterly Earnings

The best investors have a long-term orientation, focused on where a business might be in three to five years or more, rather than next quarter’s result. GE spent their time trying to please short-term investors.

“We do not worry about the stock price in the short run, and we do not worry about quarterly earnings. Our mindset is that we consistently build the company — if you do the right things, the stock price will take care of itself.” Jamie Dimon

“The investor wanting maximum results should favour companies with a truly long-range outlook concerning profits.” Phil Fisher

“We really think that an undue focus on quarterly earnings, not only is probably a bad idea for investors, but we think it’s a terrible idea for managers. If I had told our managers that we would earn three dollars and 17 1/2 cents for the quarter, you know, they might do a little fudging in order to make sure that we actually came out at that number.” Warren Buffett

Business Results Aren’t Linear

Smart investors recognise the business environment and economy are not conducive to a perfect earnings trajectory. GE failed to understand this, deploying unethical and in some case illegal short cuts to deliver.

“GE executives have acknowledged that they worked to make sure earnings were growing in a nice smooth trajectory.” Lights Out

“When Fortune’s Carol Loomis once told Welch that the smoothing practice was terrible, he vehemently disagreed with her. ‘What investor would want to buy a conglomerate like GE unless its earnings were predictable?” Lights Out

“The concept of managing earnings, another wonderful numbers term that infiltrates the numbers-pressure culture that leads to ethical collapse. It’s not cooking the books, it is managing earnings. A numbers obsession finds employees and officers not managing strategically but manipulating numbers for results.” Marianne Jennings

“Be suspicious of companies that trumpet earnings projections and growth expectations. Businesses seldom operate in a tranquil, no surprise environment, and earnings simply don't advance smoothly. Charlie and I not only don't know today what our businesses will earn next year we don't even know what they will earn next quarter. We are suspicious of those CEOs who regularly claim they do know the future and we become downright incredulous if they consistently reach their declared targets, Managers that always promise to ‘make the numbers’ will at some point be tempted to make up the numbers.” Warren Buffett

“Businesses do not meet expectations quarter after quarter and year after year. It just isn’t in the nature of running businesses. And, in our view, people that predict precisely what the future will be are either kidding investors, or they’re kidding themselves, or they’re kidding both.” Warren Buffett

Promoting the Stock

“In the [2015] annual letter, Immelt wrapped up his lecture on the limitless superlatives of GE with an awkward plea to major institutional investors.. ‘We have delivered for you in the last five years. But we are still under-owned by big investors. In this time of uncertainty, why not GE?’ he wrote, like a heartbroken lover begging for reconciliation. ‘We have a ton of cash that can protect you,’ he added.” Lights Out

“[At the annual Electrical Products Group conference for industrial investors and executives] Immelt, as he had done before, argued that investors had GE all wrong and were mispricing a stock that should have been above $30 a share.” Lights Out

“We suspect that business leaders who are busy promoting themselves or their stock are not properly focused on running their companies. We go out of our way to look for management that cares about shareholder value but doesn't hype its stock.” Marathon Asset Management

“People who have a proclivity for announcing how valuable their stock is, are I think, people who you ought to be very cautious of.” Warren Buffett

Fancy Predictions

“As the [2016] year came to an end, Immelt planted a flag that would define the rest of his career: he declared that GE would produce at least $2 of profit per share in 2018. It was an unusually long-term projection, and its meaning was undeniable to Immelt.” Lights Out

“It was wishful thinking at best that GE could deliver the $2 of earnings Immelt had promised.” Lights Out

“Charlie and I tend to be leery of companies run by CEOs who woo investors with fancy predictions. A few of these managers will prove prophetic – but others will turn out to be congenital optimists, or even charlatans. Unfortunately, it’s not easy for investors to know in advance which species they are dealing with.” Warren Buffett

Candor and Bad News

“Faced with the prospect of telling their tempestuous CEO that the new product was a disaster, the managers chose another route. They massaged the numbers.” Lights Out

“There was no market for hard truths or bad news. Not as far as the guy at the top was concerned.” Lights Out

“It was better to figure out a better way to deliver the bad news, or make it go away somehow, than to present it to Immelt straight.” Lights Out

Great businesses are tolerant of mistakes. Great Leadership recognises businesses grow through trial and error. When problems aren’t addressed they fester and the eventual impact on a business can be disastrous.

“Almost every business has problems, and we’d just as soon the manager would tell us about them. We would like that in the businesses we run. In fact, one of the things, we give very little advice to our managers, but one thing we always do say is to tell us the bad news immediately. And I don’t see why that isn’t good advice for the manager of a public company. Over time, you know, I’m positive it’s the best policy.” Warren Buffett

“Bad news concealed over time doesn’t get any better. See those studies again: companies with the most candid disclosures in their financial statements perform better over the long term and have higher share prices.Companies that put their current positions and performance right out there for investors and analysts to study are the companies to put your money in.” Marianne Jennings

A Culture of Making the Numbers

“The pressure to perform inside GE is omnipresent, and missed goals can be fatal, a tradition true at all levels of the company.” Lights Out

“Management expectation about the sales growth and profit they should be able to hit didn’t reflect the dim reality of the market, team members told Steve Bolze [CEO GE Power] and Paul McElhinney, the head of the unit that administers the service contracts. Vocal complaints about management’s view diverging from the reality of the market, or from basic math, were common among lower level Power executives. When the concerns were raised to leaders like McElhinney, they were stopped cold... ‘Get on board,’ McElhinney said. ‘We have to make the numbers.’” Lights Out

“When Immelt took over the Plastics operation, the previous management hadn’t been playing it straight. Under pressure from Welch, the division had stretched to make the numbers, including misreporting inventory figures to reduce the cost of goods sold.” Lights Out

“Welch would argue that he pushed his underlings to produce results, not fraud. But even if the CEO didn’t bend the rules himself, Welch cultivated an environment of pressure that incentivised people to do just that.” Lights Out

“If you couldn’t do the job and hit your targets, they all knew, Jack Welch would get someone else who could.” Lights Out

“Jeff Immelt’s assignment was clear: keep the earnings machine of GE humming steadily along, as it had under Welch.” Lights Out

“GE regularly leaned on [GE Capital] to make sure that profits stayed steady.” Lights Out

“Few fates were worse than missing your numbers at GE. Executives assigned targets to underlings, rather than lower-rung workers passing information up the ladder, so projections were based on market realities.” Lights Out

“Salespeople relied on financing provided by the stub of GE capital to prop up customer demand.” Lights Out

Marianne Jennings wonderful book, ‘The Seven Signs of Ethical Collapse - How to Spot Moral Meltdowns in Companies... Before It's Too Late’ cites ‘Pressure to Maintain Those Numbers’ as the number one sign of ethical collapse; “All companies experience pressure to maintain solid performance. The tension between ethics and the bottom line will al-ways be present. Indeed, such pressure motivates us and keeps us working and striving. But in this first sign of a culture at risk for ethical collapse, there is not just a focus on numbers and results but an unreasonable and unrealistic obsession with meeting quantitative goals. ‘Meet those numbers!’ is the mantra.”

“Charlie and I have been around the culture, sometimes on the board, where the ego of the CEO became very involved in meeting predictions which were impossible and everybody in the organisation knew, because they were very public about it, what these predictions were and they knew that their CEO was going to look bad if they weren’t met. And that can lead to a lot of bad things. You get enough bad things, anyway, but setting up a system that either exerts financial or psychological pressure on the people around you to do things that they probably really don’t even want to do, in order to avoid disappointing you, that’s a terrible mistake. And, you know, we’ll try to avoid it.” Warren Buffett

“We really believe in the power of incentives. And there’s these hidden incentives that we try to avoid. One we have seen more than once, is when really decent people misbehave because they felt that there was a loyalty to their CEO to present certain numbers, to deliver certain numbers, because the CEO went out and made a lot of forecasts about what the company would earn. I’ve seen a lot of misbehaviour that actually doesn’t profit anybody financially, but it’s been done merely because they don’t want to make the CEO look bad, in terms of his forecast.” Warren Buffett

“You really have to be very careful in the messages you send as a CEO. If you tell your managers you never want to disappoint Wall Street, and you want to report X per share, you may find that they start fudging figures to protect your predictions. And we try to avoid all that kind of behaviour at Berkshire. We’ve just seen too much trouble with it.” Warren Buffett

If a culture is broken and toxic the best advice is to steer clear. It’s almost impossible to turn around a poor culture.

“You can’t buy a company that’s got a dishonest culture and turn it into an honest culture." Bradley Jacobs

Cost Cutting

“The Corporate cost cutting program [was'] called ‘Simplification.’ That program had zeroed in on worker pensions and retiree health insurance as a good place to tighten the company belt.” Lights Out

'Whenever I read about some company undertaking a cost-cutting program, I know it's not a company that really knows what costs are all about. Spurts don't work in this area. The really good manager does not wake up in the morning and say, 'This is the day I'm going to cut costs,' any more than he wakes up and decides to practice breathing.'' Warren Buffett

“You can’t cut a company to greatness.” Charles Schwab

“Almost every firm engages in bouts of cost cutting. Exceptional firms, however are involved in a permanent revolution against unnecessary expenses.” Marathon Asset Management

Losing Your Competitive Position

“If a management makes bad decisions in order to hit short-term earnings targets, and consequently gets behind the eight-ball in terms of costs, customer satisfaction or brand strength, no amount of subsequent brilliance will overcome the damage that has been inflicted. Take a look at the dilemmas of managers in the auto and airline industries today as they struggle with the huge problems handed them by their predecessors. Charlie is fond of quoting Ben Franklin’s ‘An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.’ But sometimes no amount of cure will overcome the mistakes of the past.” Warren Buffett

“Companies which underinvest in their franchise in order to meet short term targets are not good candidates for compounding wealth.” Terry Smith

Accounting Irregularities

Pressure from the top to hit numbers coupled with an unwarranted focus on the share price, can tempt employees to fudge the numbers. Once again, Marianne Jennings observed, ‘A declining stock price can cause bizarre accounting behaviour. The drive for numbers, number, numbers can take us right to the slippery slope and into ethical collapse.”

“GE Power had sold service guarantees to many of its customers that extended out for decades. By tweaking its estimate of the future cost of fulfilling those contracts, it could boost its profits as needed.” Lights Out

“These reviews [of GE’s service contracts] produced profits that GE could use to hit targets for Wall Street, but they were really future profits, produced by accounting adjustments alone. There was no actual cash coming in… [They] can be red flags to investors… To pad the hole, GE now began selling its receivables - bills its customers owed over time - to GE Capital in order to generate short-term cashflow, making it appear that those newfound profits were matched by cash flowing in the door.” Lights Out

“The SEC concluded its investigations into GE accounting practices, having found multiple instances of misbehaviour in the pursuit of financial targets. The company had overstated its earnings by hundreds of millions of dollars and stretched the accounting rules to their breaking point.” Lights Out

“The SEC described [GE as] a company that lied to investors in its regulatory filings and in its public statements, that ignored growing risks, and that worked to keep those risks hidden.” Lights Out

“Over the years, Charlie and I have seen all sorts of bad corporate behaviour, both accounting and operational, induced by the desire of management to meet Wall Street expectations.” Warren Buffett

Hitting Guidance

“What starts as an ‘innocent’ fudge in order to not disappoint “the Street” – say, trade-loading at quarter-end, turning a blind eye to rising insurance losses, or drawing down a “cookie-jar” reserve – can become the first step toward full-fledged fraud. Playing with the numbers ‘just this once’ may well be the CEO’s intent; it’s seldom the end result. And if it’s okay for the boss to cheat a little, it’s easy for subordinates to rationalise similar behaviour.” Warren Buffett

Acquisitions & Divestments

Immelt wanted to appease Wall Street and convince them to place a higher multiple on the stock. Historically GE had enjoyed a premium valuation providing the currency for accretive acquisitions. As GE Capital grew, a complex finance business within an industrial company, Wall Street applied a lower multiple. Immelt believed shrinking GE Capital would fix the problem.

“GE could use its unusually high price-to-earnings ratio for an industrial company as high-value currency to pay for deals. By acquiring companies with a lower price-to-earnings ratio, GE was getting an automatic earnings boost.” Lights Out

“Immelt needed to make moves that would finally impress upon Wall Street that he had found a way to lead the old GE into a new economic paradigm.” Lights Out

Capital Management

“GE had been sending cash out the door to repurchase its stock but wasn’t bringing in enough cash from its regular operations to cover its dividend.” Lights Out

“Buybacks were a regular fixture under Immelt, who spent more than $108 billion on them after 2004. At the end of 2018, GE’s entire market value was $67 billion.” Lights Out

Group Think

“The oversight role of the board was minimal.” Lights Out

“The board, made up of current and retired business executives and academics, as a group, liked Immelt and didn’t want to challenge him.” Lights Out

“Top GE executives, including Immelt, would say that they never heard any serious dissent about the Alstom deal.” Lights Out

“The absence of robust opposition [to the Alstom deal] also pointed to the broader problem, long cultivated and growing into a quiet crisis within the company of real candor and self-awareness. When it had come time for lower levels of management to stand up to the ultimate boss and tell him that his legacy play wasn’t going to work - and in fact, had been a clumsy mistake all along - no-one was willing to do so.” Lights Out

“Vice Chair John Krenecki, insiders said, had been forced out by Immelt, in part because he had already seemed a little too prone to disagreeing with the CEO or telling him no.” Lights Out

“GE’s board of directors was unquestionably weakened from having the CEO as the chairman of the Board.” Lights Out

“While Immelt said he encouraged debate, [Board] meetings often lacked critical questioning.” Lights Out

“The seventeen independent directors got a mix of cash, stock, and other perks worth more than $300,000 a year.” Lights Out

“[Board] directors rarely challenged Immelt.” Lights Out

“The [Board] directors had amassed impressive titles in their own career and in many cases undeniable achievement. They had resumes a yard long, most of them had personal fortunes, and they were presumed in all company to have unusually astute minds for business - not least because each one was a highly compensated director of GE. And yet, on their fiduciary watch, with whatever caveats about individual misjudgement and macroeconomic trends, they had done nothing to stop one of the world’s most solid industrial companies from lunging off a commercial cliff.” Lights Out

“Sycophants are the enablers of ethical collapse. Fear and silence are the enemies of an ethical culture.” Marianne Jennings

“If you arrange your organisation so that you basically have a bunch of sycophants who are cloaked in titles, you are going to leave your prior conclusions intact, and you’re going to get whatever you go in with your biases wanting. And the board is not going to be much of a check on that. I’ve seen very, very few boards that can stand up to the CEO on something that’s important to the CEO and just say, you know, ‘You’re not going to get it.’” Warren Buffett

Complexity

“Inside GE’s legendary management machine was a complex mechanism that used [GE Capital’s] deals to help the company meet its profit goals.” Lights Out

“GE Capital was always a problem. It was utterly complex and filled with risk, and its tentacles reached everywhere in the company.” Lights Out

“[The financial services] balance sheets were treacherously complex, and deep risks lurked there and were not always easily spotted in the quarterly profits and losses.” Lights Out

“[GE Capital was] essentially operating a high-powered hedge fund.” Lights Out

“Where you have complexity, by nature you can have fraud and mistakes.. This will always be true of financial companies. If you want accurate numbers from financial companies, you’re in the wrong world.” Charlie Munger

Cyclical Industries

GE ventured into the highly cyclical oil business with optimistic forecasts, little experience and no margin of safety.

“GE was going big into the oil business.” Lights Out

“Now GE became, in a series of high-dollar acquisitions, a player in the oil and gas equipment market virtually overnight.” Lights Out

“While Immelt heard, and was annoyed by, the chirping of some analysts who felt he’d paid a premium to leap into the oil and gas industry several years after his competitors, the company’s leadership was sure that the ensuing years would show the bet payoff.” Lights Out

“GE’s ‘base case’ assumption for all of the rosy pictures it was painting about its oil unit was $100 for a barrel of oil. Brent crude had closed out the previous month at more than $105 a barrel, only a little off its summer peak.” Lights Out

“Afloat on fracking profits during an oil boom, Lufkin had caught GE’s eye and been swallowed up at an expensive price, only to become a casualty when the conglomerate couldn’t abide the hit to earnings that a prolonged dip in the price of oil represented.” Lights Out

Insurance Tail Risks

“Everyone - reporters, analysts, investors - thought that the company had sold the insurance business long ago, significantly de-risking GE Capital. In often highlighting this point, Immelt and his top executives hadn’t minced words: GE was out of insurance.” Lights Out

“The core problem was that GE had made some bad decisions in reinsuring the long-term care policies.” Lights Out

“GE needed $15 billion to cover its liability.” Lights Out

"Virtually all surprises in insurance are unpleasant ones." Warren Buffett

“You can make big mistakes in insurance… You can make mistakes in something like insurance reserving, big time.” Warren Buffett

Bigger than Life CEO

Jeff Immelt almost personified the ‘bigger-than-life’ CEO. It’s a characterisation Marianne Jennings identified as another red flag for investors.

“Immelt knew the power of his influence, and he wasn’t above calling these subordinates [below the divisional heads] to make sure they knew the stakes and urge them to hit their targets.” Lights Out

“The structural component that fuels fear and silence and numbers pressure is the presence of an iconic CEO who is adored by the community, media, and just about anyone at a distance.” Marianne Jennings

Humility & Tone from the Top

“Immelt was required by the board to use only the company’s planes and was barred from flying commercial.” Lights Out

“Immelt, his good cheer notwithstanding, was not interested in hearing his judgement questioned. ‘My job is to make the company perform,’ Immelt told a newspaper reporter, ‘and my job is to make sure that nobody defines this company other than me.” Lights Out

“[Owning GE Capital meant] Immelt enjoyed having the accompanying seat at the table with Wall Street power players.” Lights Out

“Owning NBC gave Immelt and Welch access to red carpets.” Lights Out

“It had taken two corporate jets to take Jeff Immelt around the world. For much of his career [Immelt] often had an empty jet follow his GE-owned Bombardier or Gulfstream to far-flung destinations, just in case there was a mechanical issue that could lead to delays.” Lights Out

“No effort was spared by the staff to ensure that meeting venues were cooled to meat-locker temperatures to accommodate Immelt’s preference, irrespective of whether anyone had ever heard him make such a demand out loud.” Lights Out

“Was a CEO supposed to object that the temperature was not to his liking, or demand that elevators were always open and waiting for him? Or that the cold diet sodas he liked were always present on a sideboard when he entered a room, no matter how far-flung the visit or conference room he walked into?” Lights Out

“But GE has stood for well-bred hubris as well. Under Immelt, the company believed that the will to hit a target could supersede the math, even when hundred of thousands of livelihoods - those of investors, customers, and suppliers, to say nothing of workers, retirees, and their families - hung in the balance." Lights Out

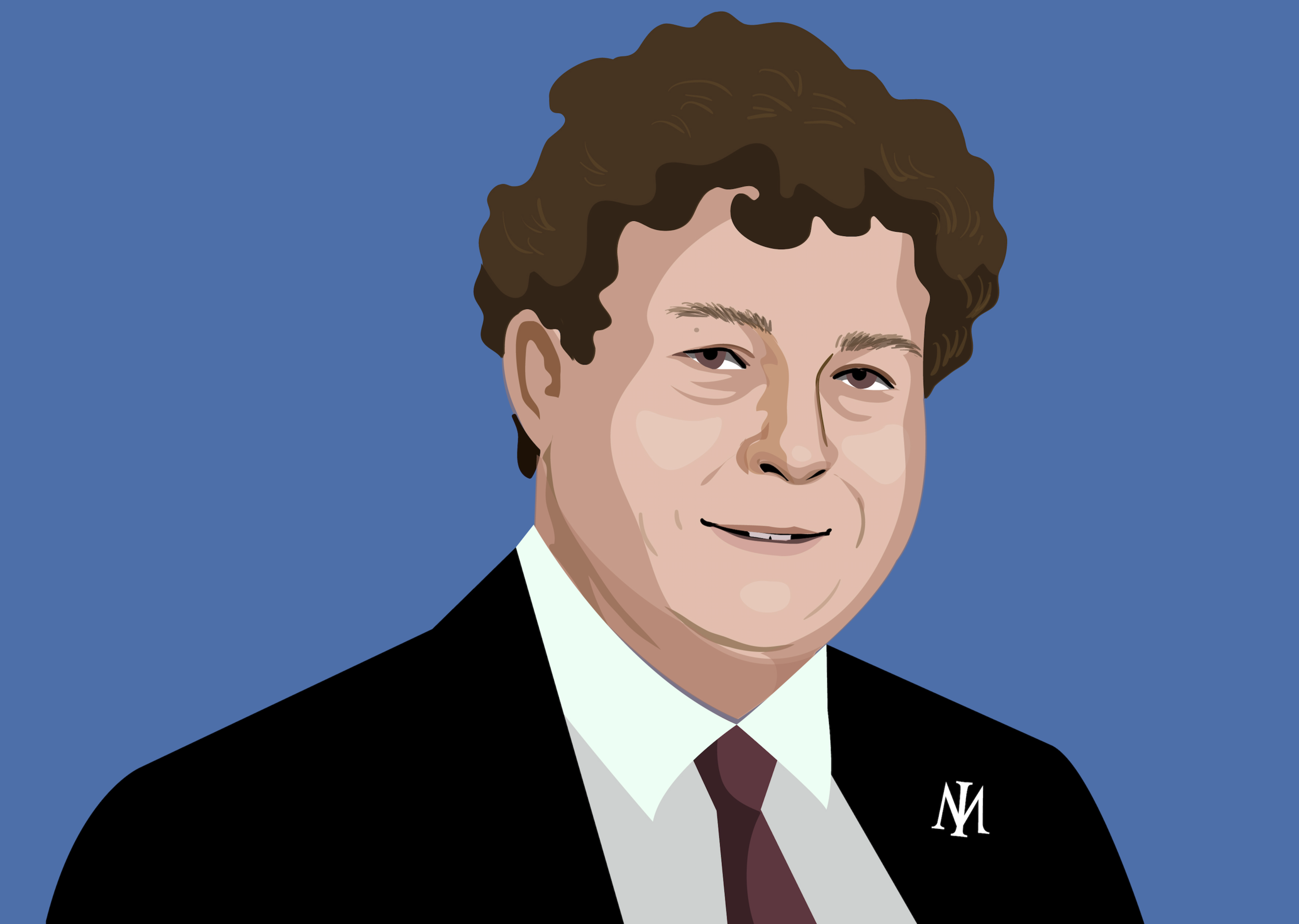

Smart Investors

The emergence of a smart investor on the register is no panacea for investment success. Activist investor Nelson Peltz’s fund emerged with a $2.5 billion stake in 2015. Even the great investors make mistakes.

“Trian’s endorsement was the stamp of approval that Immelt thought would help others realise the full legitimacy of GE’s expected turnaround.” Lights Out

“In every great stock market disaster or fraud, there is always one or two great investors invested in the thing all the way down. Enron, dot-com, banks, always ‘smart guys’ involved all the way down.” Jim Chanos

Summary

The ‘pressure to maintain those numbers’, a culture of ‘fear and silence’, a bigger-than-life CEO, and a weak board conspired against the investors of General Electric; red flags that stand firmly in the qualitative camp, not to be found in a spreadsheet.

These misdeeds aren’t unique or new to investing. After more than two decades of research and observation, Marianne Jennings identified each of them in her book, ‘The Seven Signs of Ethical Collapse.’ They didn’t go amiss at Berkshire either, given Munger and Buffett’s astute understanding of human behaviour.

History is littered with similar corporate disasters to GE. They serve as a warning for analysts, investors, portfolio managers, boards and CEO’s alike; Forewarned is forearmed. Understanding those qualitative tools that may suggest not all’s right with a company might help you ‘keep the lights on,’ when the next GE turns up.

“I think that many CEOs get carried away into folly. They haven’t studied the past models of disaster enough and they’re not risk-averse enough.” Charlie Munger

Source:

“Lights Out - Pride, Delusion and the Fall of General Electric,” by Ted Mann and Thomas Gryta, Mariner Books, 2020.

Further Suggested Reading:

“The Ten Commandments of Business Failure,” Investment Masters Class, 2016.

“The Seven Signs of Ethical Collapse - How to Spot Moral Meltdowns in Companies... Before It's Too Late,” Marianne Jennings, MacMillan, 2006.

“Avoiding Group Think,” Investment Masters Class, 2016.

Follow us on Twitter : @mastersinvest

* NEW * Visit the Blog Archive

TERMS OF USE: DISCLAIMER

![S&P500 [grey] vs General Electric [blue] Normalised - 2000 - 2021 [Source: Bloomberg]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/568cf1da4bf1182258ed49cc/1626240958557-MQY5UOVVQ98IF9CHHKM1/Screen+Shot+2021-07-14+at+3.33.36+pm.png)

![Estée Lauder vs SP500 1995-2021 [Source: Bloomberg]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/568cf1da4bf1182258ed49cc/1622953763962-A339S3D8A10QJA6BVXPE/Screen+Shot+2021-06-06+at+2.28.10+pm.png)

![Dow Jones Industrial Average - 1987 Crash [Source; Bloomberg].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/568cf1da4bf1182258ed49cc/1616478903417-5MBL252INY28HCUPDPYG/dow.PNG)

![Disney Corporation vs S&P500 - March 2005 to 2021 [Source: Bloomberg]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/568cf1da4bf1182258ed49cc/1613102921408-U4VQK7OGPQ515OR2Y2LI/dischart.JPG)

![COPART Share Price vs S&P500 Normalised [Source: Bloomberg]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/568cf1da4bf1182258ed49cc/1590377897583-CI4565VVKZN2GM15HXZ2/Screen+Shot+2020-05-25+at+1.37.52+pm.png)